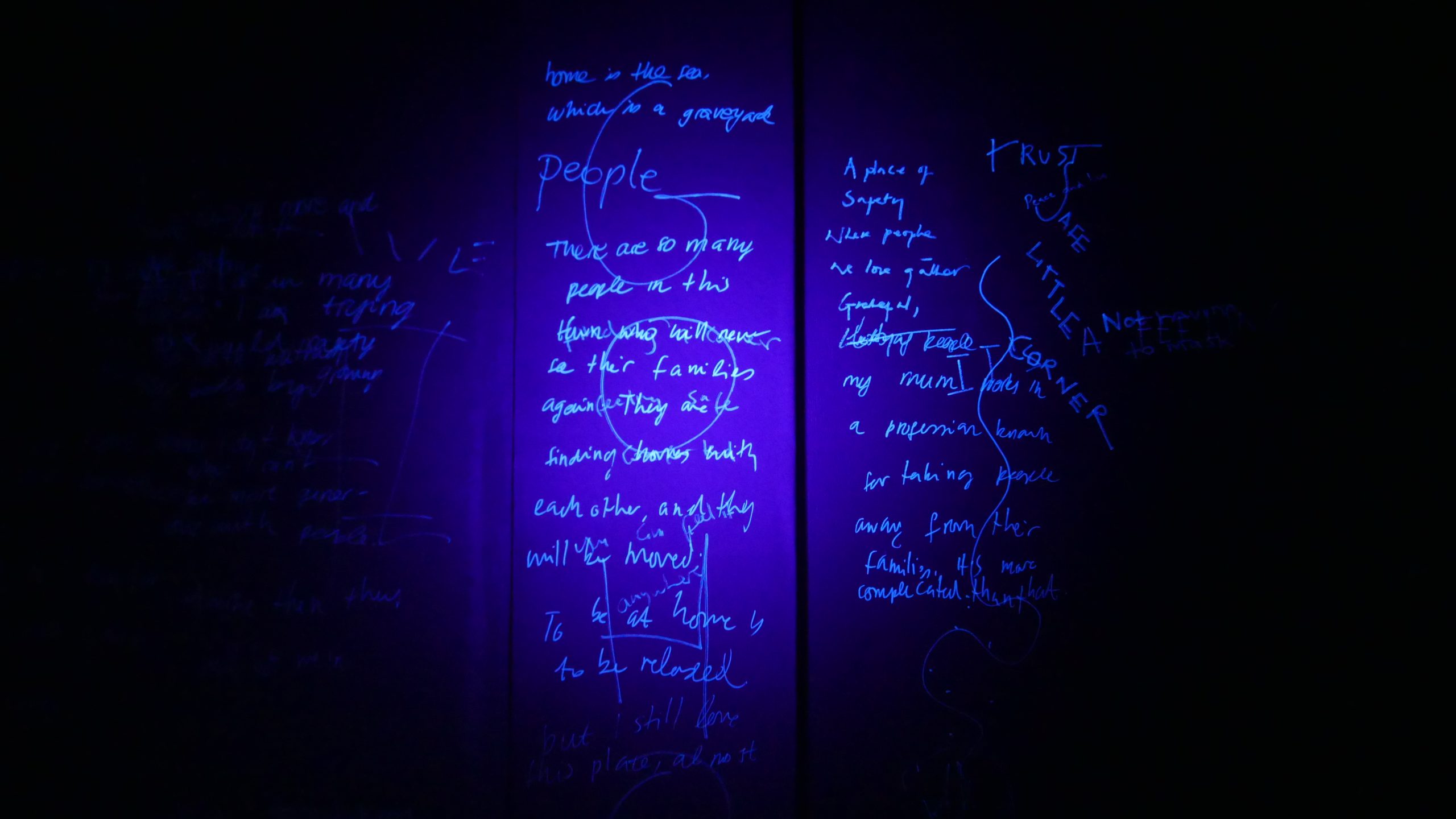

The Oko early warning satellite system was operated from an underground bunker in the military townlet of Serpukhov-15, near Kurilovo. This is where the command would be sent from to launch a retaliatory missile strike; deep underground, far from anything that is happening on the surface. The perception of events above ground are channelled through flows of data, radar, and computer signal processing.

To begin my research, I decided to go for a walk, virtually, trying to get as close as possible to the bunker as I could. Obviously the exact location is not readily available but from geosatellite imagery, I spot a compound that features several huge white dome structures that suggest a site used for surveillance and listening via antennas.

My walk takes me through a woodland of what looks like mostly firs and birches on a beautifully sunny day with clear skies, or at least it was when Google cars were driving along these same roads surveying the scene. At the closest point to the compound, I find a gathering of cars, a few drivers are milling around – I wonder what they are doing here, what brings them to the outskirts of this military townlet?

As I’m moving/clicking forward, I’m thinking how such major decisions about world-changing events are made from places that are concealed and hidden from public view. I’m struck by what a contrast it makes; beneath this tranquil woodland lies a facility constructed to command the launch of deadly missiles.