bursting

A little BTS of the recording of the Champs cover we did a couple weeks ago. A treat to celebrate England getting to the finals tonight! Enjoy the game!

video description: Hang Linton sits in a home music studio with dark grey soundproofing foam on the white walls and white and yellow speakers in the background, wearing black headphones, a white tshirt and black twists in his hair. In the background is a wide but small window with cream curtains, it looks sunny outside. On the window sill there is a gold lucky waving cat. Hang sings with a twisted pained look on his face, sweating from the heat, the camera zooming into his face.

![Black screen with white font subtitle at the bottom [sound of subtitles]](https://vitalcapacities.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screenshot-2021-07-11-at-18.26.07-1024x283.png)

![Black screen with white font subtitle at the bottom [music and sound fades]](https://vitalcapacities.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Screenshot-2021-07-11-at-18.25.53-1024x278.png)

These two images are the beginning and the end of the video work titled [sound of subtitles].

I recently discovered Aine O’Hara’s work online. Their theatre piece pictured above, GAA MAAD, is all about being a queer footy fan in Ireland and the rejection and abuse that comes with that.

I’m really interested in fandom, the way we attach ourselves to specific teams, players, fighters etc but I especially love the way crowds move and ripple and thrash about together. It was strange and surreal to see a mass of static cardboard cutouts or screens of fans at home during the pandemic, as well as the fake crowd noise.

I also like it when they do close ups on the telly of disappointed and sad fans when their team is losing, even better if they are really dressed up for the occasion with face paint, a comedy hat and a flag wrapped around them, decorating their downturned face.

An improvised film test of the muscle costume and PE kit made for me by Max Allen with a new song that I’m making with Hang Linton. A million points to anyone who can figure out where the sample in the song is from or who it is.. I just tried out some different poses and gestures from my research, some different lighting and filmed it on a phone on my studio bed.

Visual Description: I’m wearing a sheer mesh muscle suit, long sleeved top and trousers, and a shiny blonde mullet wig, my own naked body is visible underneath. I am washed in orange light, stood on a white platform in a white room with a dark coloured floor. I pose and flex like a body builder and pull strained open mouthed faces. I am wearing a footy tabard over the top of the muscle suit, it has ‘FORGOT ME PE KIT’ and ‘Ladette’ written on it, it’s blue and red. I’m washed in a bright green light. I lift a footy banner or scarf that says ‘BUGGER OFF’ on it, it has tassles hanging from it, I’m swaying from side to side, I drop it to the floor and direct my right arm out to the side as if declaring something. I am back to wearing just the muscle suit and wig, this time washed in a gentle blue light and lying down on the bed, flexing and posing and pulling strained open mouthed faces.

Audio Description: An electronic bassline track that sounds a little bit like Prodigy with some trip-hop spacey tones thrown in. It features a repeated sample of a middle aged person with a strong accent that is probably from Essex or the East End of London saying in an irritated voice, ‘A loada rubbish, them lot up in the Houses of Parliament, terrible’.

![A block of text with black bold fonts on white background. It says the following- [soaring orchestra music] [sound of remembering fondly] [♪♪♪] [sound of shifting relationship] [mysterious string music] [sound of emptiness in the room] [dramatic theme swelling] [sound of communicating gently] [***] [sound of world shattering] [somber music] [sound of shaping context] [music gets faster] [sound of still silence] [music intensifies] [sound of whispering sweet nothings] [music and sound fades]. The musical one [♪♪♪] is in dark blue colour.](https://vitalcapacities.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/postcardimage-1024x576.jpg)

![Screen capture of video with white font subtitle with black background. All 3 stills of video from videos are identical and are placed side by side. They are black and white images of clay covered hands shaping a round shaped pottery on wheel. The person is wearing long sleeved shirt that is rolled up at lower arms. The images have different subtitles. On the left image it reads [turning], middle image reads [sound of remembering fondly], the right image reads [soaring orchestra music].](https://vitalcapacities.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Screenshot-2021-06-29-at-17.42.29-1024x275.png)

![Screen capture of video with white font subtitle with black background. All 3 stills of video from videos are identical and are placed side by side. They are coloured images of clay covered hands shaping pottery on a wheel. These images have different subtitles. On the left video it reads [holding], middle video reads [sound of listening inward], the right video reads [♪♪♪].](https://vitalcapacities.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Screenshot-2021-06-29-at-17.42.40-1024x277.png)

![Screen capture of video with white font subtitle with black background. All 3 stills of video from videos are identical and are placed side by side. They are coloured images of clay covered hands shaping brown pottery on wheel. The images have different subtitles. On the left it reads [shaping], the middle video reads [sound of emptiness in the room], and the right reads [mysterious string music].](https://vitalcapacities.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Screenshot-2021-06-29-at-17.42.51-1024x277.png)

[turning] [sound of remembering fondly] [soaring orchestra music] [holding] [sound of listening inward] [♪♪♪] [shaping] [sound of emptiness in the room] [mysterious string music]

Audio will be silent in my piece for the final outcome of this residency- I aim for the subtitles to show the endless possibilities of what the words would sound like for the viewers.

I have been experimenting with multiple videos using Premiere Pro and After Effects. It has been a daunting task to figure out the dimensions and creating subtitles! This is a snippet of what I’ve been working on today in the impromptu ‘studio’ space- a quickly emptied out space in a small living room wall where I pushed the sofa to the side to create enough space for the video projection. There are three videos playing at once, all are the same videos of hand throwing the wheel, shaping round-shaped pottery. On individual screens, there are different subtitles, on left there is an ‘action’ based subtitle ([turning] & [creating shape]) and in the middle, there’s the abstract subtitle ([sound of shifting relationship] & [sound of remembering]) and on right there’s a ‘music’ based subtitle([Dramatic theme playing] & [♪♪♪]). This video is originally from Craft / Potting / Bookbinding Practice Film from Bexley Local Studies & Archive Centre located in London’s Screen Archives. I am going in the direction where I would like to experiment with the same video but with different subtitles to ‘alter’ the experience for the viewer – changing the perception of the event with the poetic language of the subtitle.

![Screen capture of 3 videos playing side by side, each individual video shows a pair of hands shaping brown clay pottery on wheel. Each individual video has white subtitles on a black background- the video on the left reads [throwing], the middle video reads [sound of emptiness in the room], the video on the right reads[dramatic theme playing]. All three videos are on black box.](https://vitalcapacities.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Screenshot-2021-06-28-at-17.08.28-1024x317.png)

![Screen capture of 3 videos playing side by side, each video shows a pair of hands shaping brown clay pottery on the wheel. The individual videos have white subtitles on a black background. The subtitle on the left reads [gently holding], the middle subtitle reads [sound of listening inward], the right subtitle reads [soaring orchestra music]. All three videos are on black box.](https://vitalcapacities.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Screenshot-2021-06-28-at-17.08.36-1024x318.png)

This week, I am planning to experiment with multiple different videos and show these simultaneously at a more playful pace. Please leave a reply to this post to comment or ask any questions if you have any! 🙂

I would like to share some subtitles I have collected in my notes on my phone.

Music-related: [Music and sound fades] [Soaring orchestra music] [Music intensifies] [Mysterious string music] [Somber Music] [Dramatic theme swelling] [Dramatic string music builds] [Music gets faster] [♪♪♪] [***]

Action-related: [humming] [screaming] [breathing] [footsteps approaching] [crying] [wailing] [chattering] [sighing] [sobbing] [yawning]

How can these ‘objective’ subtitle be poetic in its own way? Below are some I’ve wrote.

[Sound of shaping context] [Sound of shifting relationship] [Sound of still silence] [Sound of emptiness in the room] [Sound of seeing] [Sound of communicating gently] [Sound of listening inward] [Sound of whispering sweet nothings] [Sound of worlds shattering] [Sound of remembering fondly]

Getting towards the end of this residency and my body feels close to a burn out. Working while your six month old wakes you up every hour during the night like a sleep torture program has been.. hard. My insides are starting to jolt and shudder.

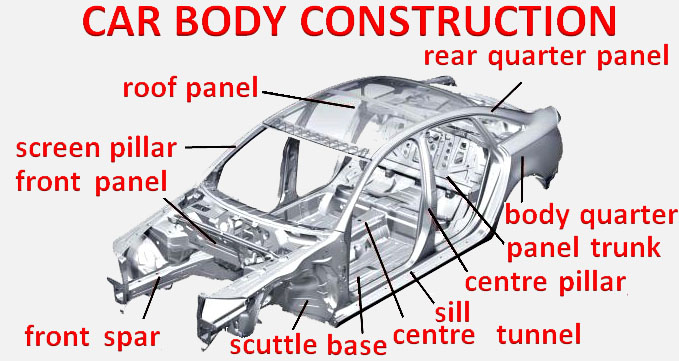

I have been considering the way we describe the shell of an automobile as a ‘body’, an external casing which holds in all of the car or lorry’s guts. There are auto body repair shops for when you damage your body or car and truck body builders for when you want an upgrade.

Researching this also led me to a strange trend of body builders (the weight lifting type) posing with their cars and this amazingly comical article to help body builders choose the best car for them which says ..

‘As bodybuilders, you cannot survive without a car. A good and big car will not only look proportional to you but will also serve your needs adequately.’

And of course there is the ‘sports car’.

These automobile bodies can be symbols of wealth, power, authority, capitalism, work, burn out or protest. During times of social unrest and resistance, the news and media is often littered with images and videos of burning cars (ACAB). When our physical bodies become exhausted by the pressures of capitalism and the inequalities of structural oppression, we also burn out and break down.

I like to think of myself as a monster truck; big, slow, colourful and garish, with very little functional use other than for fun.. a performative body that rests a lot and comes out bouncing and blazing for a show every so often when I feel like it, only to inevitably and predictably crash and burn at the end.

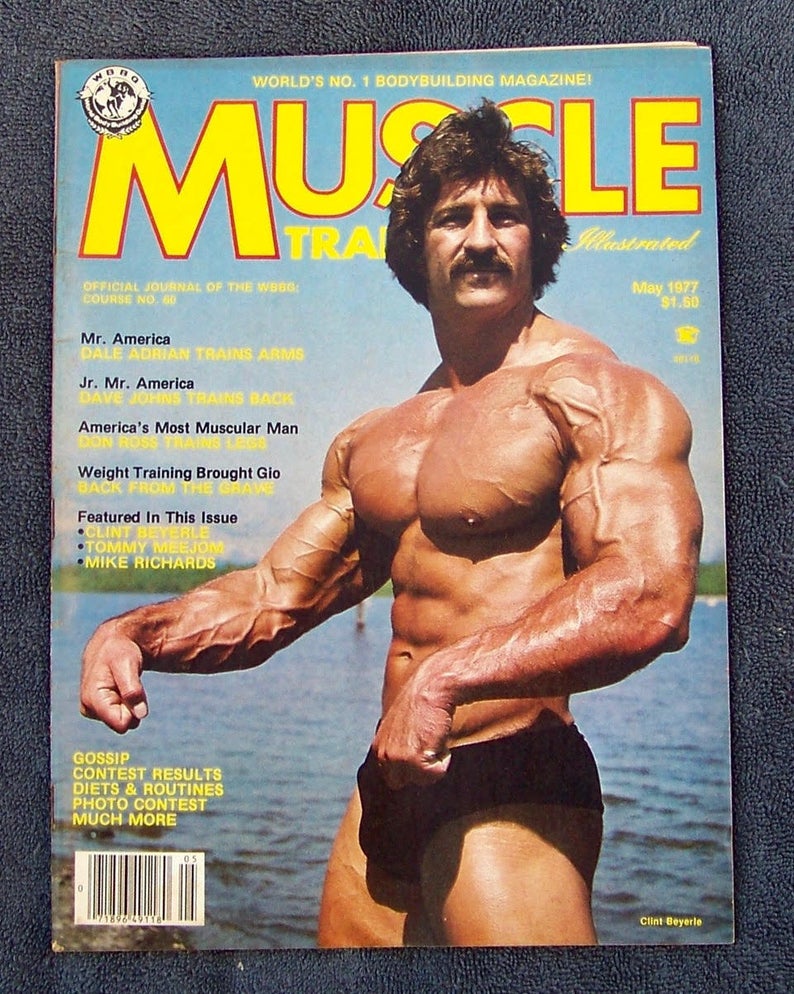

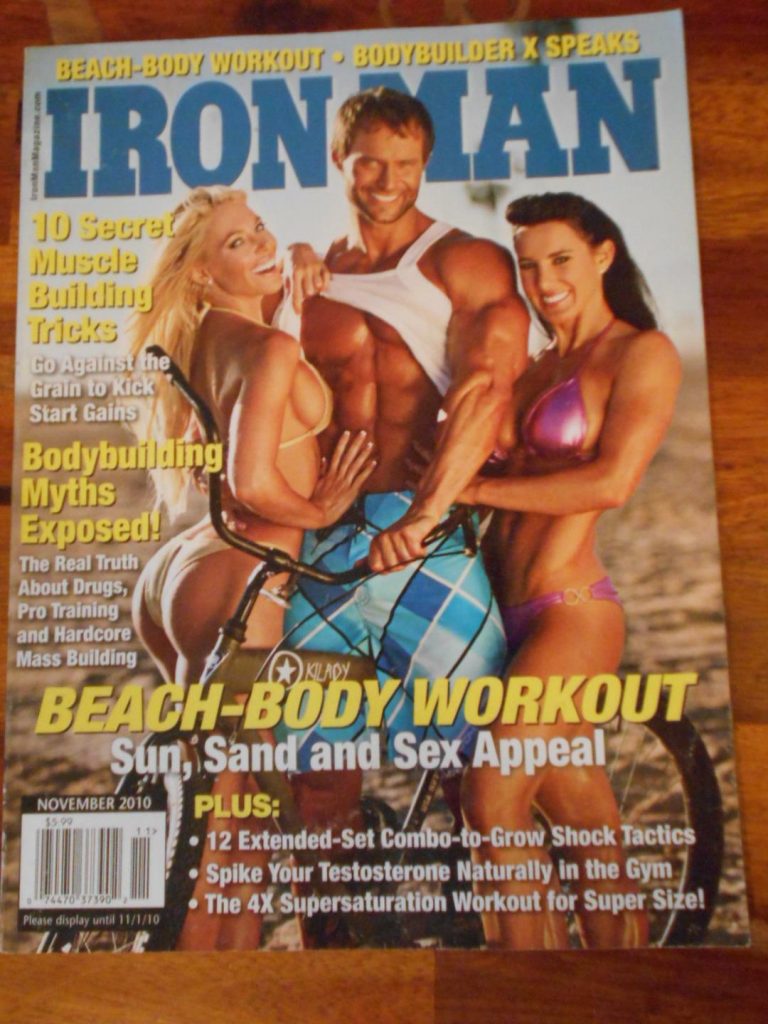

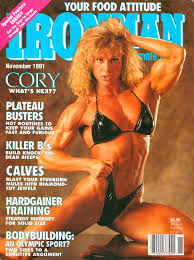

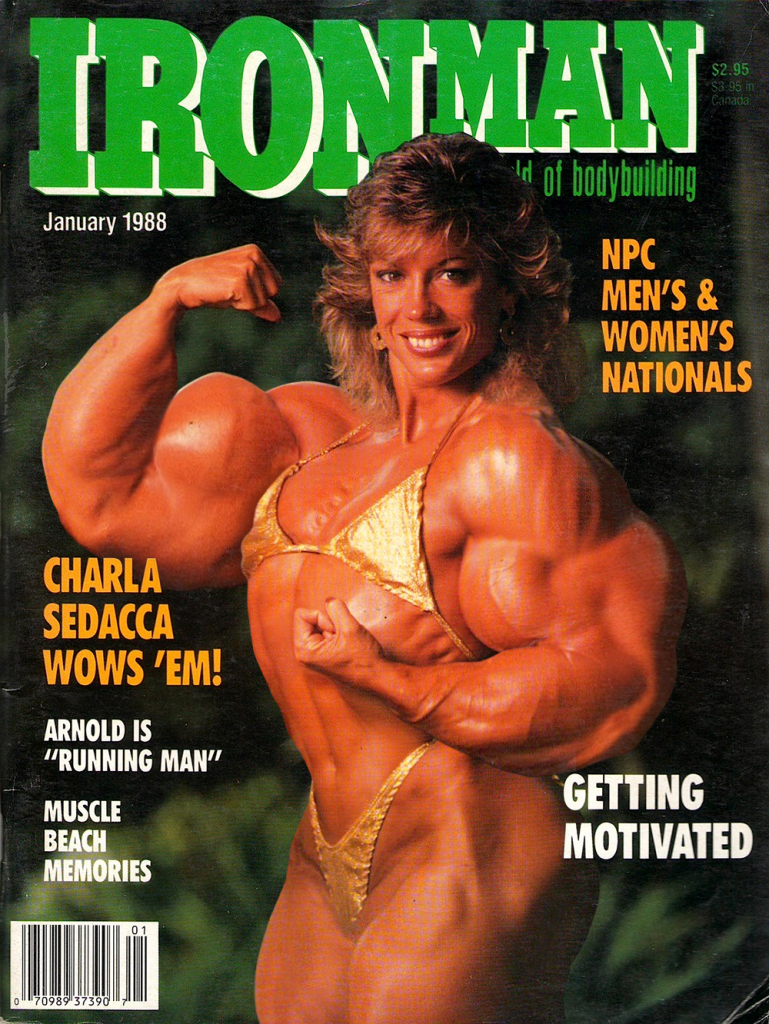

I’ve been researching bodybuilder poses, the reasons for them and the way they accentuate the muscle definition. Scrolling through Google images at these magazine covers, there are obvious themes that arise. The women are very rarely as muscly as the men, they are often used as props to the central male figure or they are overtly feminised and sexualised in bikinis with big flowing hair. I couldn’t find any magazine covers with any variation of this apart from Renee Campbell, a bodybuilder who is trying to challenge the standard look. There weren’t any covers of her but the photos from an article on CNN definitely had a different energy and aesthetic.

The positions range from intimidating to comical, one of my favourites is the one where they look like they’re pushing an invisible shopping trolley. When I look at a lot of these images and bodies all at once, shiny, bulging, smiling, angry, tanned, flexed bodies, it starts to make me feel weird, they remind me of rotisserie chickens just spinning on repeat. But they are also somehow very fascinating and impressive.

The limitations of mobility that pushing your body to this size causes makes me wonder if they are really hyperable or if they are just a visual symbol of hyperability.

This is an experiment into creating my own hybrid Frankenstein mascot monster bodies in footy diving positions. I would love to do this with irl second hand mascot bodies one day for an installation, taking a few apart and sewing bits back together, so it’s cool to be able to do some digital mock-ups and think about how I can use them sculpturally in an online exhibition to accompany the video work. I’m thinking about some t-shirts one day maybe too. I’m looking forward to developing this idea and creating more of these.

This was created with A LOT of help from Hang Linton and their stellar photoshop skills.

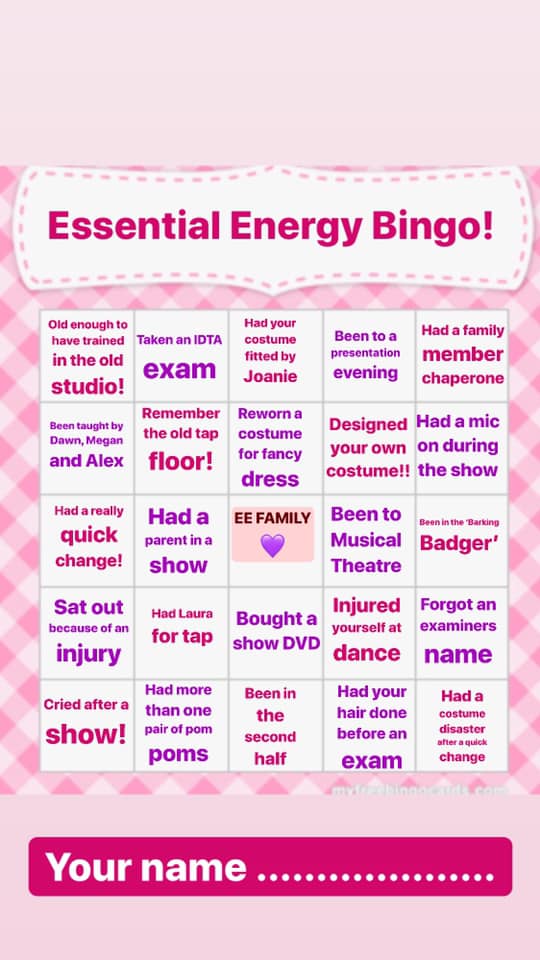

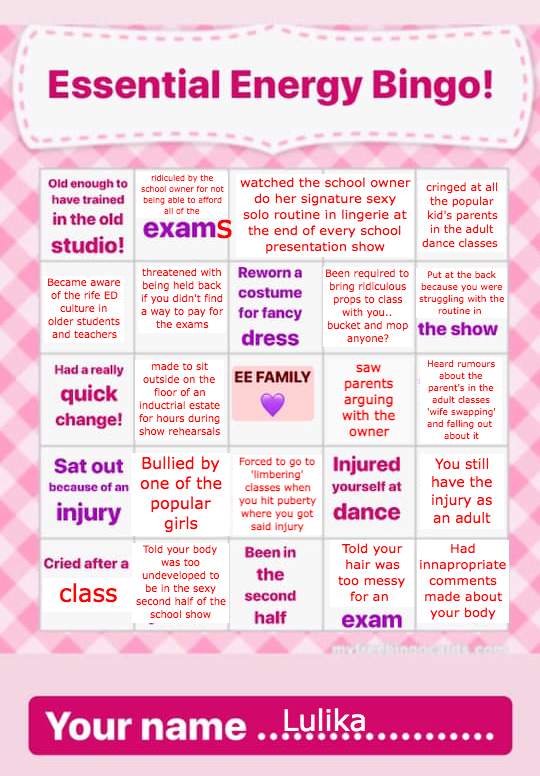

I think the closest I ever got to athleticism was attending the local dance school, Essential Energy, as a child and young teenager. I refused to do P.E at school because I hated doing hockey and netball in the freezing cold, but I spent an untold amount of hours at this tiny dance hall on an industrial estate in the Midlands.

Recently my sister sent me this bingo that a former student had made about the school that they had posted on Facebook. We couldn’t help but coming up with our own version because it was such a toxic place to be as a child learning about your body… so here it is, Essential Energy Bingo.. The Real Version (made in collab with my sister who would like to stay anonymous lol):

I have been working with fashion designer, Max Allen, to literally build a body. You can see the final product in my studio. I am going to use this costume for a choreographic film experiment, superimposing this performative figure onto my own physical body. Here is some of our inspo:

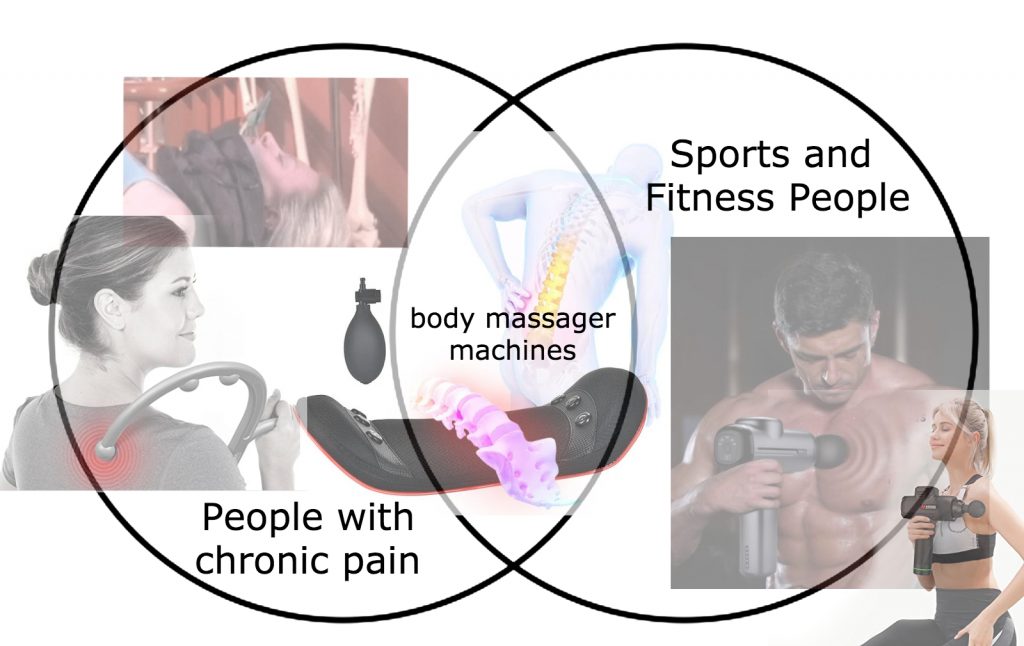

I am really interested in the aesthetic, performative and sculptural qualities of at-home health, care and wellness apparatus. I have used some in the past within installations and performance costumes. The vast array available symbolises a huge deficit in the care we receive from conventional Western health care systems. Many people seek out different types of at-home remedies due to a lack of access to a diagnosis and the required treatments, usually as a result of the structural ableism, racism, classism and fatphobia that is rampant within our healthcare institutions.

I noticed recently that one of these items, at-home self massaging devices, have become appealing to another group. I have always known them in the context of people with chronic pain but I recently saw adverts containing sports personalities endorsing them for pain related to sporting activities.

I find the way these items are advertised often very creepy and unsettling. They are usually demonstrated by perfectly polished and glowing, mannequin-like or cyborg-esque, smiling slim white women. I don’t think anyone really looks like this when they are reaching in desperation and pain for their neck hammock or ice pack hat, I definitely don’t.