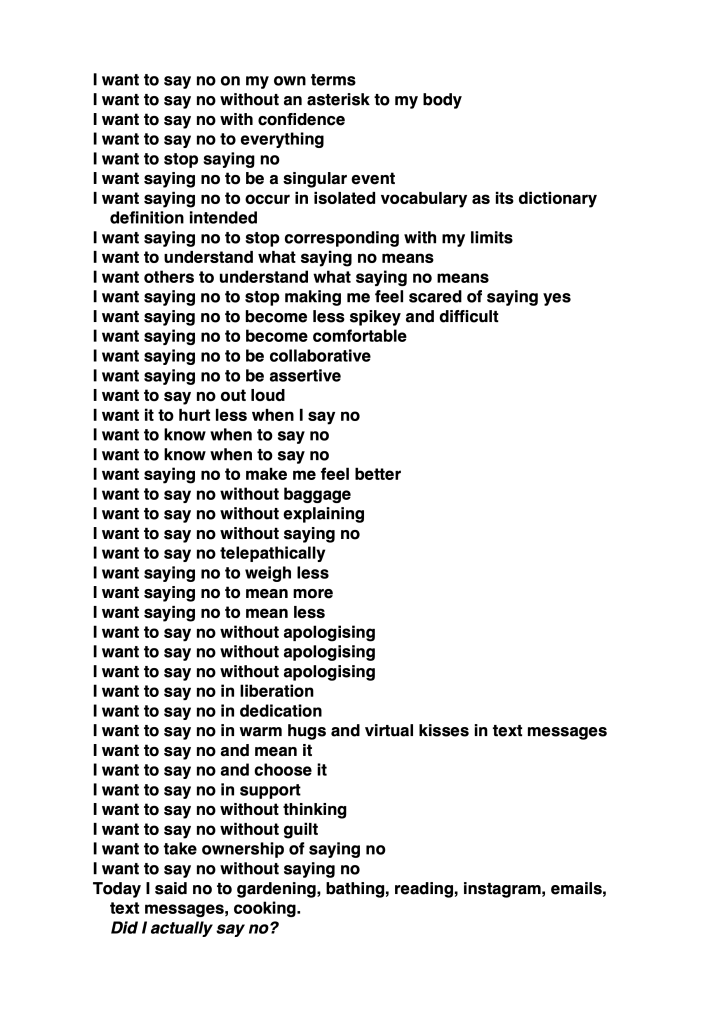

I thought about Polly Atkin’s poem Unwalking (referenced in my last post) a lot when i first returned back to my allotment plot in January 2022, having not visiting the site for 2 years due to shielding. We had been given formal notice by the allotment committee to either improve the plot or end our tenancy. I was in the midst of an intensely difficult period in my life, and I was unsure of whether the commitment was possible to continue. i was trying to figure out having a career as an artist whilst being sick, and how to do those things in a sustainable way that doesn’t just leave you burnt out. I believe that this figuring out will be a lifelong mission, one that never has a fixed answer. I still go through periods (just very recently in fact), where it feels like living in this body feels truly incompatible with a career as an artist. But what did become clear when returning to my allotment in 2022, was that in rediscovering my gardening practice, I could do something more than just survive my body and my job; i could build something bigger, something beyond myself. I decided to give myself 6 weeks and to see what might happen…

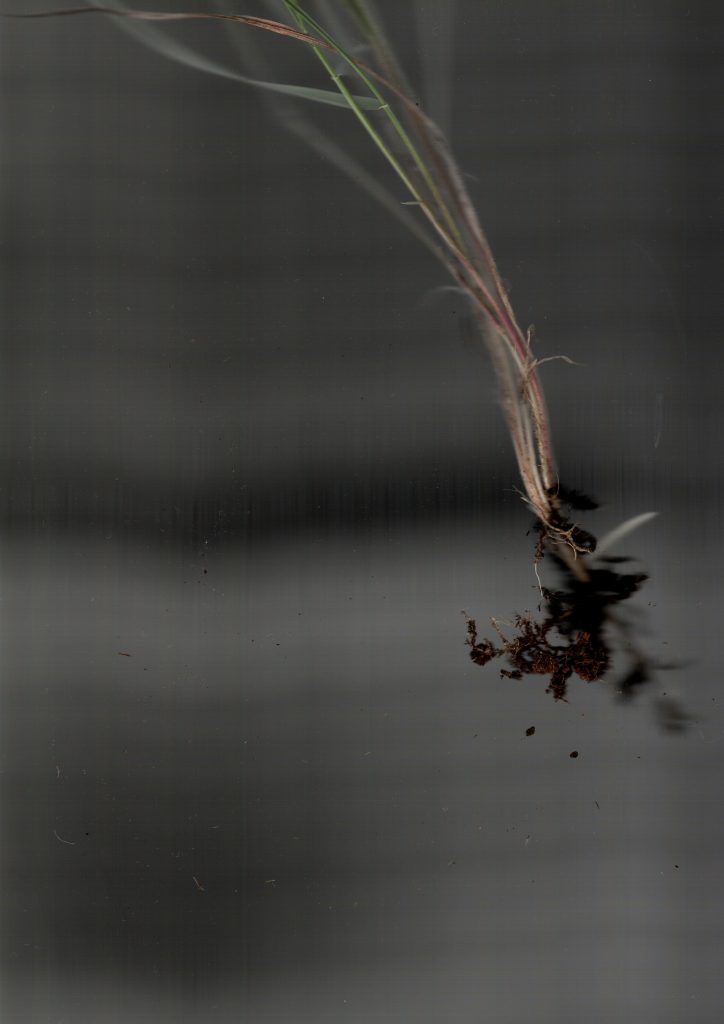

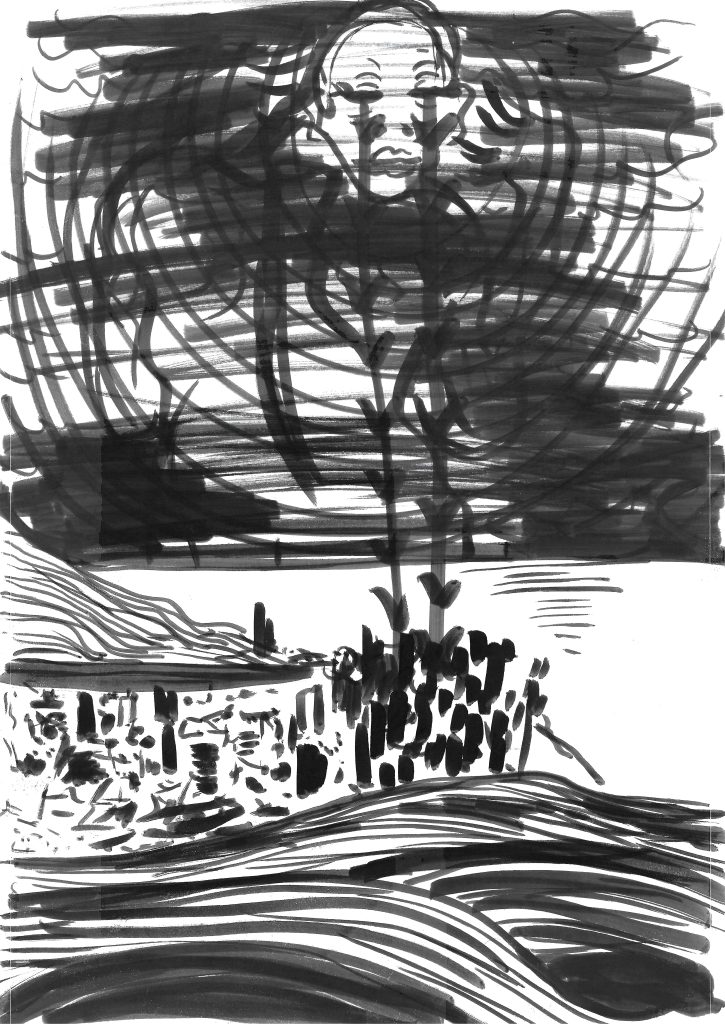

This was the first photo i took of what the plot looked like when I first returned back in January 2022. It was such a special afternoon. it was a weekday and I had been working, and my mum had asked if I wanted to go to the plot just to have a look. I was reluctant. part of having an energy-limiting condition means that i never know when i am over exerting myself, and i am always second guessing myself as to whether or not the thing i did is what made my pain worse. It’s a particularly challenging aspect of living with sickness, and something I find really hard within the context of a career. So re-engaging with the allotment again on a normal working day felt pretty extreme; simply leaving the house and turning up felt like i was pushing my boundaries of what was possible (it always does). But that afternoon, i felt the spark of what has always drawn me to gardening, and amongst all the overgrown weeds and debris, i felt excited to think what might be possible here.

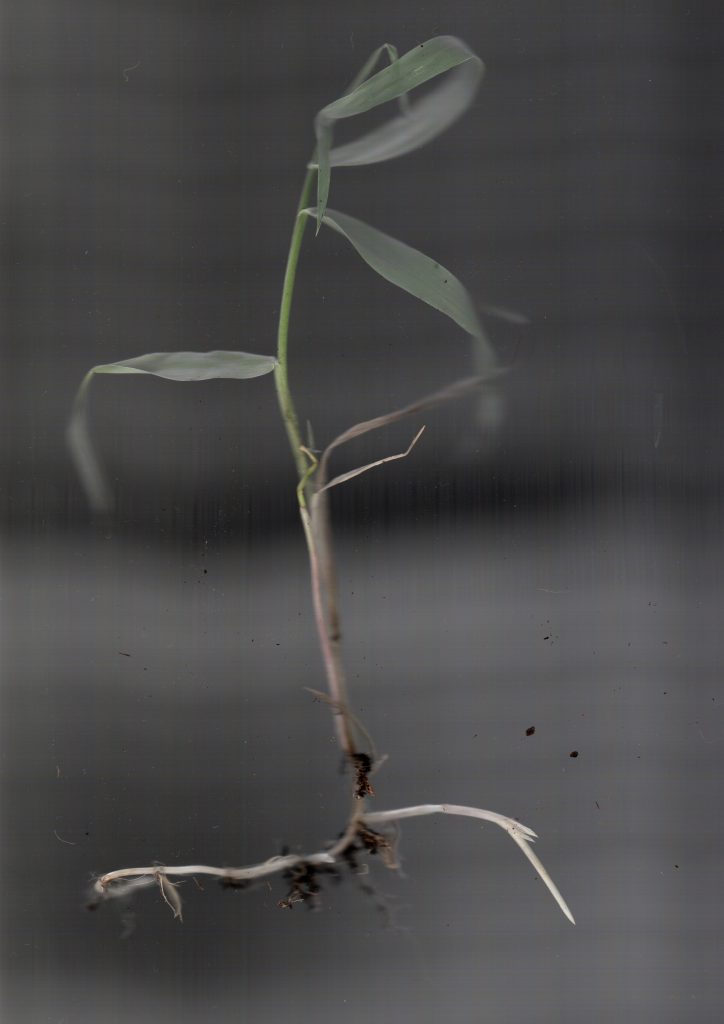

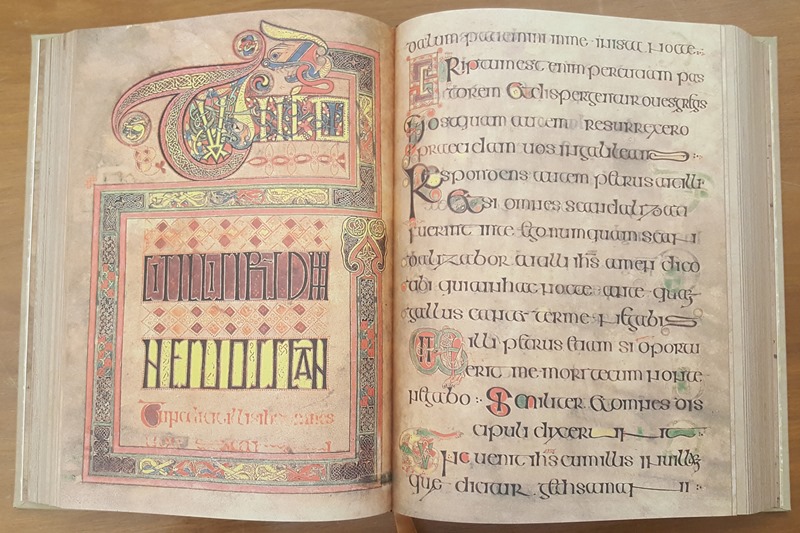

Polly’s poem Unwalking was in my head a lot as we began grappling with how to go about using the space again. It became clear quite quickly, that the only way to manage the space at this point – whilst existing in crip-time – was to cover most of it up. So that’s what the first year was spent doing; taking things down and very slowly mulching and covering the beds. We began by adopting a no-dig approach by placing cardboard over the beds, then covering them in a mulch of compost or manure.

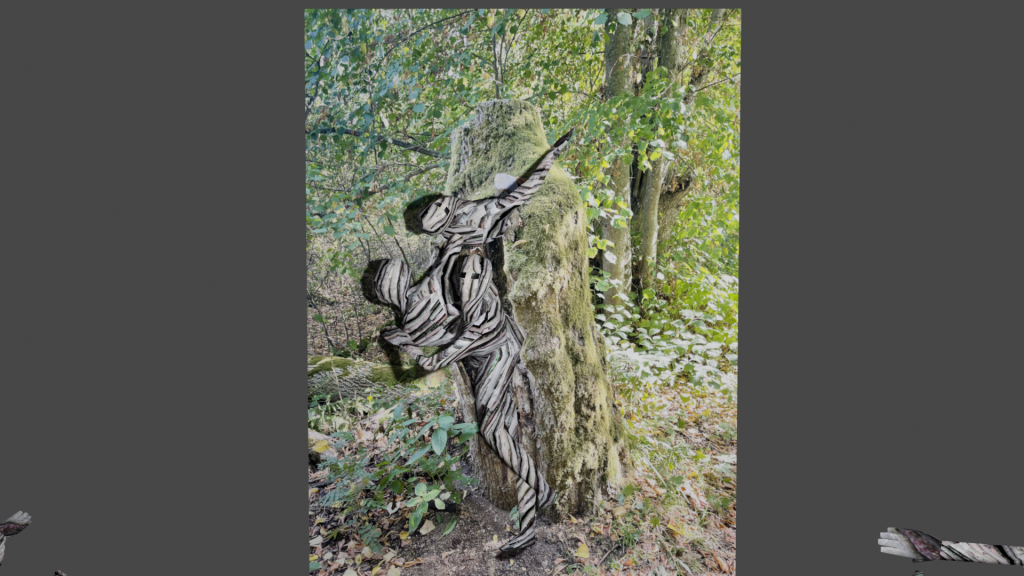

This mulching process was so exciting; it felt like i was making these large scale collages with muck and cardboard. Again, scale becomes a really exciting component of what draws me to this gardening practice. I love feeling in awe of bigness, to feel like i’m in the presence of something much, much bigger than me. I think i’m always searching (even in the smallest of artworks i make) for the feeling i get when i’m next to a huge lump of gritstone rock at Curbar Edge, my local rock face in the Peak District National Park. It’s the same feeling i get when i experience Wolfgang Tillmans work in the flesh, where the bigness just carries me away across landscapes and into another space. When mulching and covering the beds at the allotment, all of a sudden it moved beyond an ordinary gardening task and became a kind of space-making.

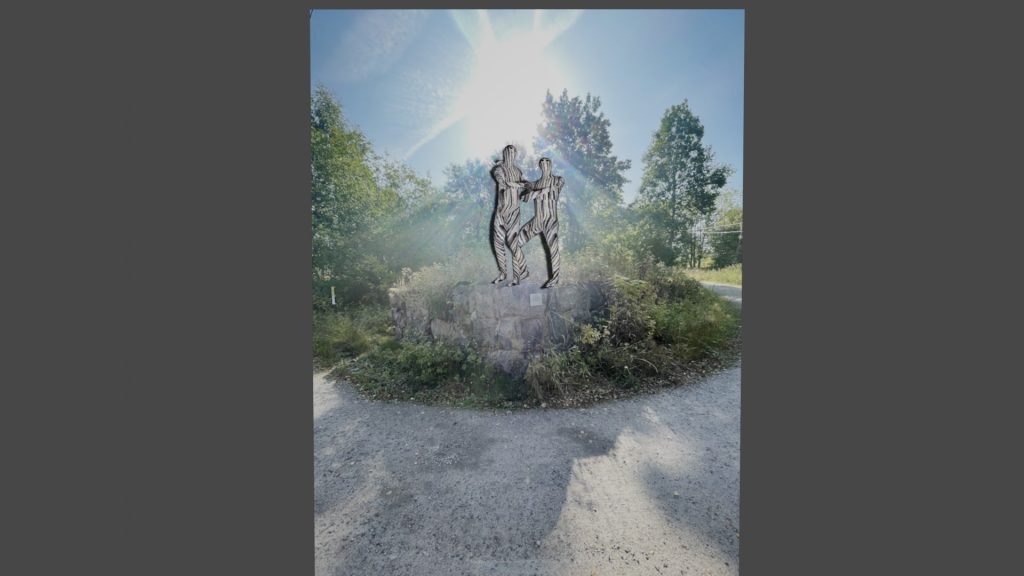

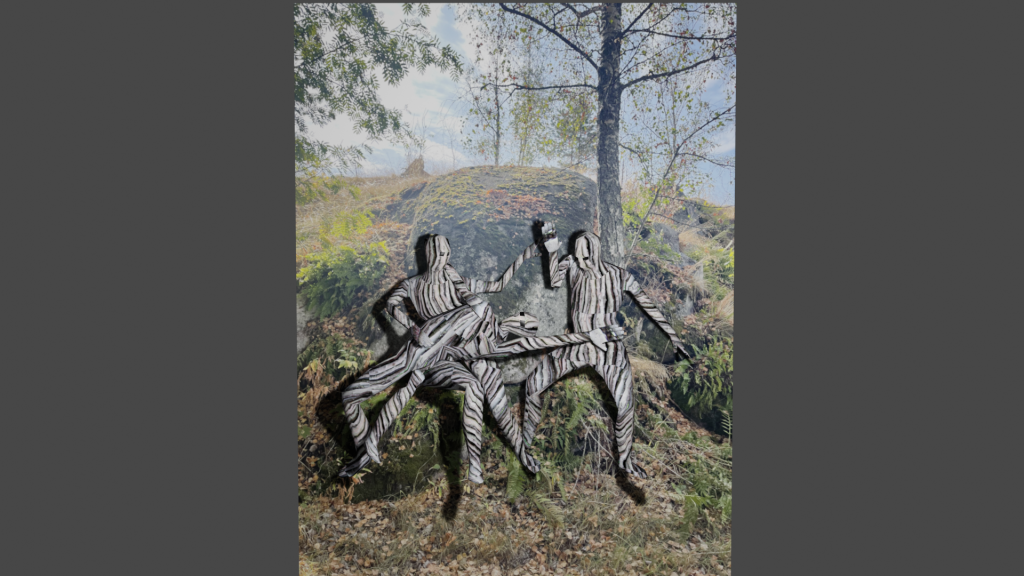

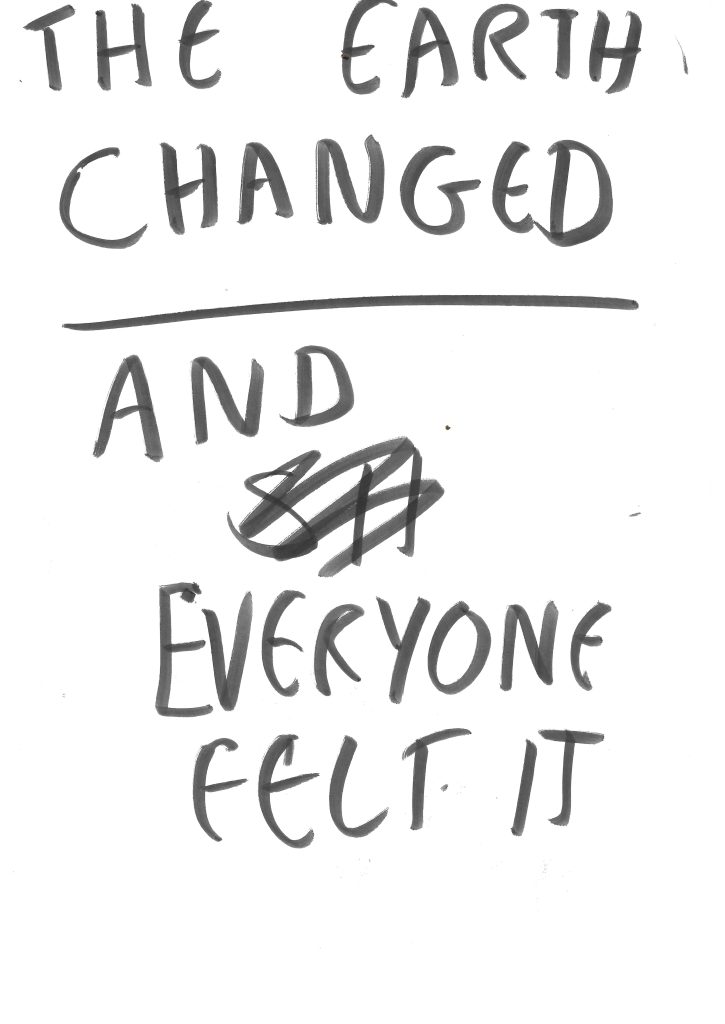

I often describe my work building the rose garden (and maintaining an allotment plot in general) as totally absurd; trying to get my sick and tired body to sculpt this huge space simply feels a bit ridiculous when met with what that space demands of my very limited energy. It feels like i’m being asked to hold the space up as if it were some kind of giant inflatable shape, and all i have are my tired arms to try and keep it from falling over and rolling away. Sometimes it feels like the chanting at a football match, the way the chorus from the crowd at one and the same time feel both like a buoyant wave of singing and a crash of noise imploding; always on the edge of collapse. And I do have help. it would be impossible to do it without it, and wrong of me not to clarify this essential component of my access to this practice. And even with this, the task at hand still feels enormous. But i think that might be part of what fuels the work in this way. This whole existence – enduring/living/loving through sickness – is absurd. It’s an outrageous request that is demanded of our bodies, of our minds, of our spirit. But I think i’m interested in what happens when I sit with sickness, hold hands with it, move through this world by its side instead of operating from a place of abandon or rejection or cure. I want to hold myself holding sickness, and find the vast landscapes within upon which to settle.

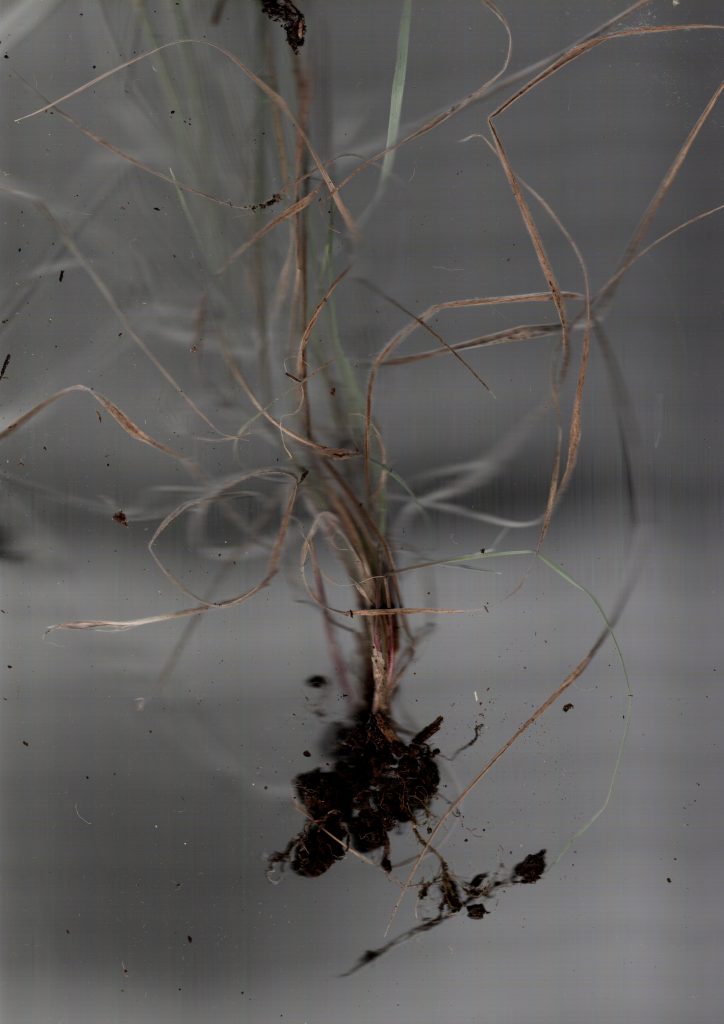

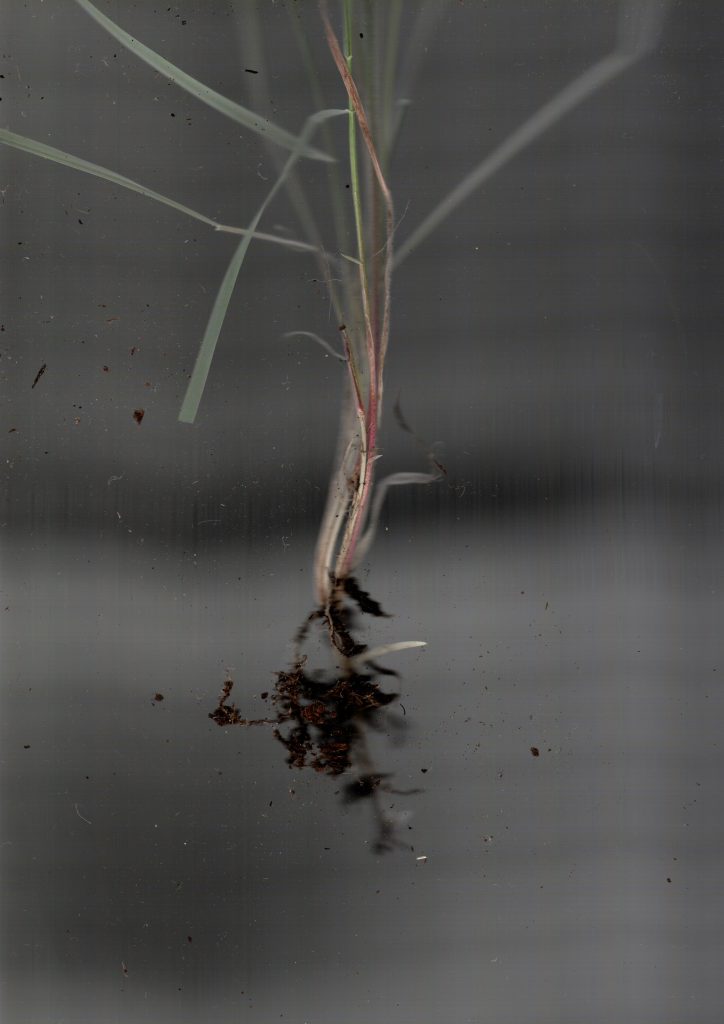

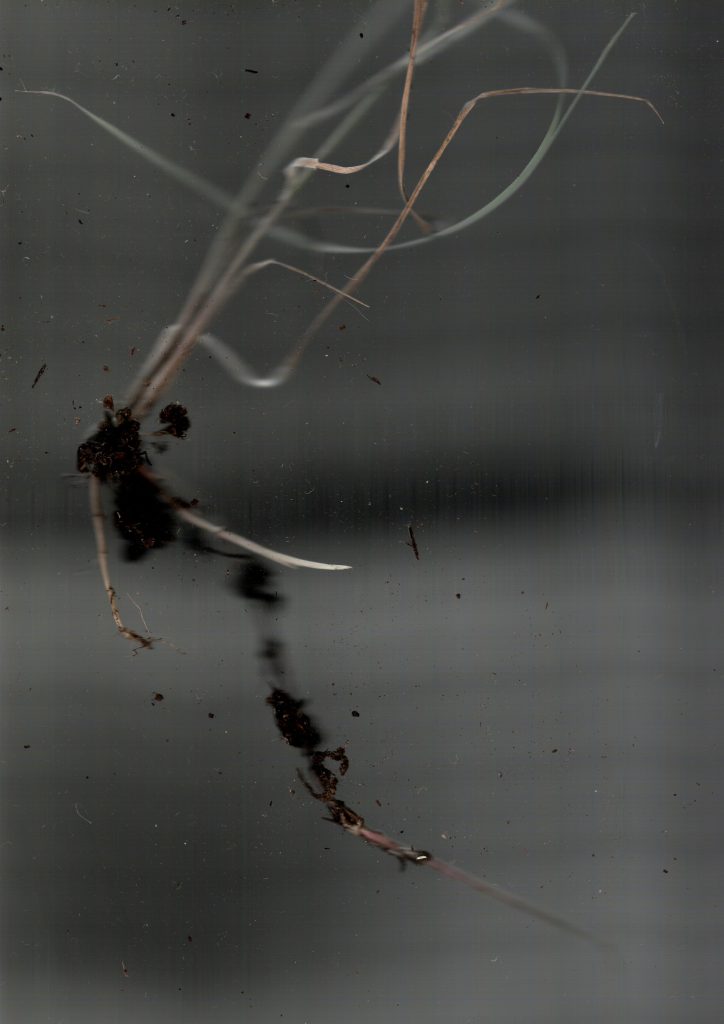

After heavily mulching the cardboard we then covered the beds in black plastic sheeting to block out all light, and allow the weeds to rot down into the soil ready for planting in the autumn. This really enhanced the sense that i was working with a kind of collage. The beds immediately looked like covered up swimming pools, and i loved playing with the various allotment debris that we had gathered to weigh down the sheeting. This whole process took up the entire first year of the work we did on the plot. There was little to no “proper” gardening (as in sowing/planting/cultivating) in that first year. And yet, I was there, I was at home dreaming about it, I was making something, committing time and energy to a place with a hope to emerge into a future. All the components of a garden were present; I was ungardening.

Despite the plot now looking significantly different to that first year, i am still ungardening. As with everything that is allowed to work on crip-time, ungardening facilitates whole ways of experiencing the garden that would otherwise be lost. Ungardening allows for me to keep my body at the centre of my gardening practice, and for the garden to exist beyond me. rather than a singular space, the garden becomes a shifting, interconnected ground of thinking and growing and imagining and living and dying. more than anything, ungardening reminds me that the garden is made for made for my absence, and my absence holds more than a missing body.