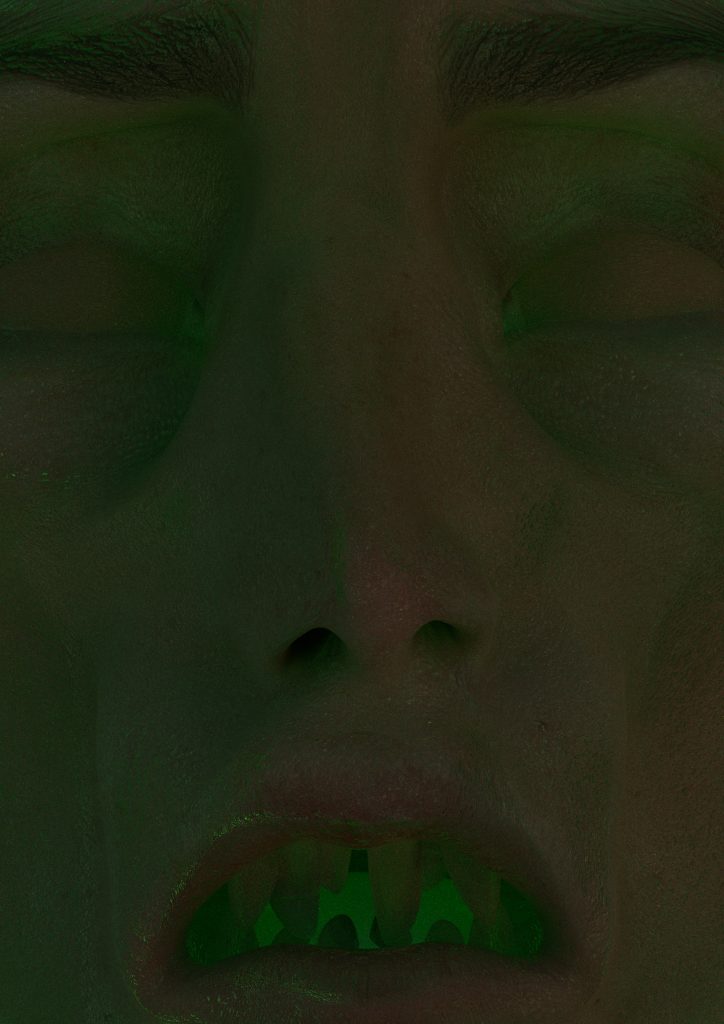

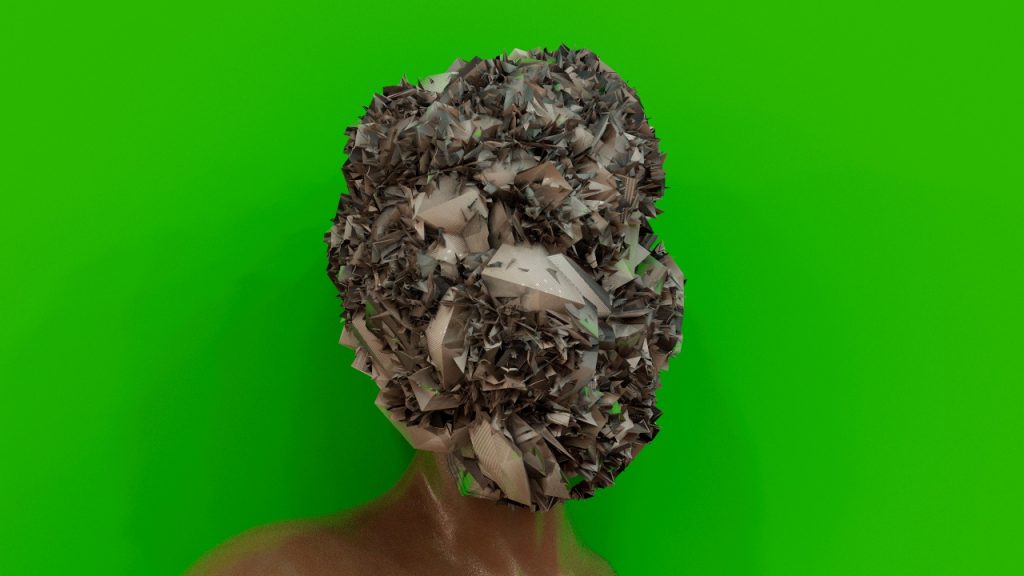

a recent face

today i have been developing a character that could represent chaos, Chaos is often personified as female within mythology, and usually defined as the anarchic mix of elements that existed in the Universe. Being born of no mother, father or matter – chaos is self-knowing about everything that happens in the Universe and beyond every moment and is ”omnipotent’’.

I am thinking that in the film the character can be splitting and morphing, i have experimented with this in previous works, but now rather than being a distortion i want to imagine how chaos can take shape in a bodily form 🙂

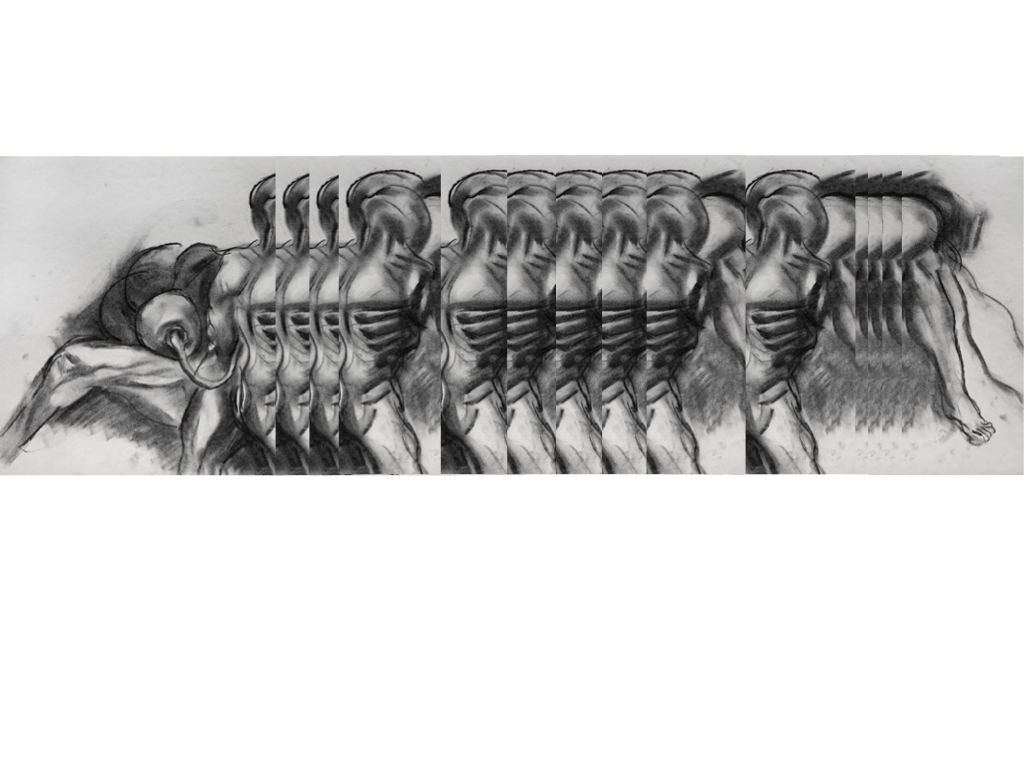

And i have also been creating some characters that blur representations of mythological figures

this was an experiment with a centaur figure, me and jennifer have always loved using a horses in our work and with this work we are interested in blurring the line between human and animal.

O Lord, I am so lonely and despaired.

I cry out for your help.

My soul is empty and restless.

Fill it with your glory, O Lord!

Anima Sola

Alone, I am lonely. Alone, I feel lost and afraid. Alone, I have no one to talk to. Alone, people do not understand me. Alone, there is no one to listen to my troubles and worries.

God, please help me find someone who will be my friend and companion for life!

Anima sola, anima Christi,

per quam tibi nos reconciliamur.

O Maria, Mater Dei et hominum,

terribilis ut castrorum acies ordinata,

tu ades cunctis in periculis nostris.

Oh God,

I am alone in this world.

It is you I must rely on, and only you.

Oh Lord, I call to you for help.

Alone I am,

and yet not alone.

I am surrounded by a thousand angels,

who wait for me to join them in the Kingdom of Heaven.

I wait for them as well.”

I came across the phrase Anima Sola through a recent edition of Phoebe Hildegard‘s newsletter (if ur into TTRPG’s, necromancy and Spiritualism, it’s VERY good, big recommend). I find the Anima Sola prayer super interesting. Firstly, as a tradition borne of the living working on behalf of the dead, (and specifically the ‘dead in need‘ too, something a lot of contemporary necromantic traditions generally shy away from) I find it to be, honestly, very moving. Secondly, it’s an unusual prayer in the sense that it puts the person intoning it into the shoes of the ‘lost soul’; to say the prayer is to experience their destitution as if it is ur own. On the one hand, this obviously makes it a potent prayer for those who’s experience of loneliness and despair does align with that of the anima sola. But also, it could in turn be a kind of declaration of care, and potentially even of friendship: as those performing the prayer could even be saying, “friend, let me take that load off you for a minute, I’ll help u carry ur burden”.

a way to think about death and decomposition when it comes to 3D models. digital flys cover the bodies but they show no sign of decay, seemingly staying animated beyond their death

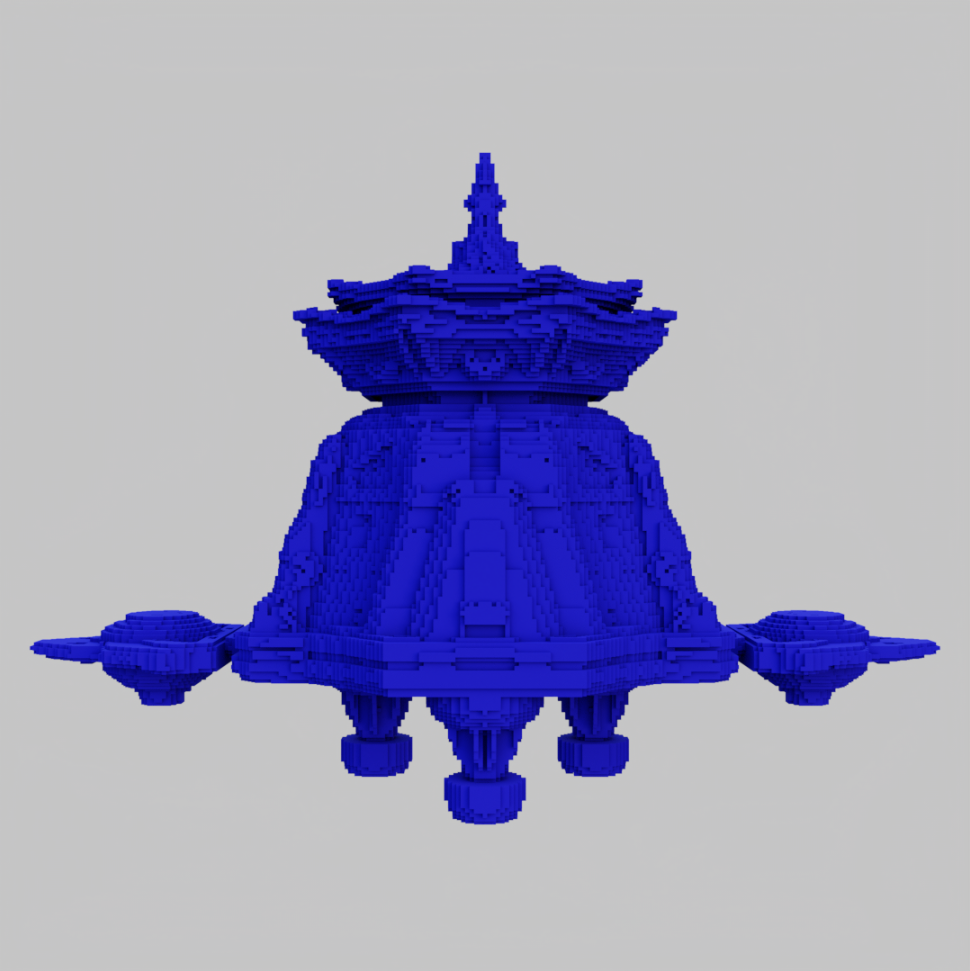

The Digigrave is a “spaceship”.

A spaceship which offers a different perspective of reviewing ourselves, to escape from those who’s addicted to grand narratives of groups, categories, ethics, or families. It looks like a Taiwanese traditional tomb, and also recalls the memory of Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall built during the 1980s. It’s part of the sci-fi story Space Warriors. According to the story setting, Digigrave carries alien species to come and save the earth – or the island under martial law.In East Asia, during the last decade of the Cold War from 1984 to 1987, CTS, one of Taiwan’s only three official TV stations at that time, produced and broadcasted a very rare and weird sci-fi series, Space Warriors. It was basically copied from the Japanese series Super Sentai in late 1970s with modifications. At the same time, it also referenced the Gavan, the follow-up series of Super Sentai, and was mixed with some local elements. CTS eventually discontinued the series due to low ratings, inconsistent production quality, overt criticism from parents, and the import of the Japanese original on VHS and satellite television. Unfortunately, the sci-fi did not open the people’s imaginative thoughts about the universe and the world, but rather, the series, combined with illogical fantasy and Chinese Folktales and even martial arts elements, subtly implied nationalism, Confucianism, patriarchy, and other values, which was a very strange and unique experience during the martial law period.

2021

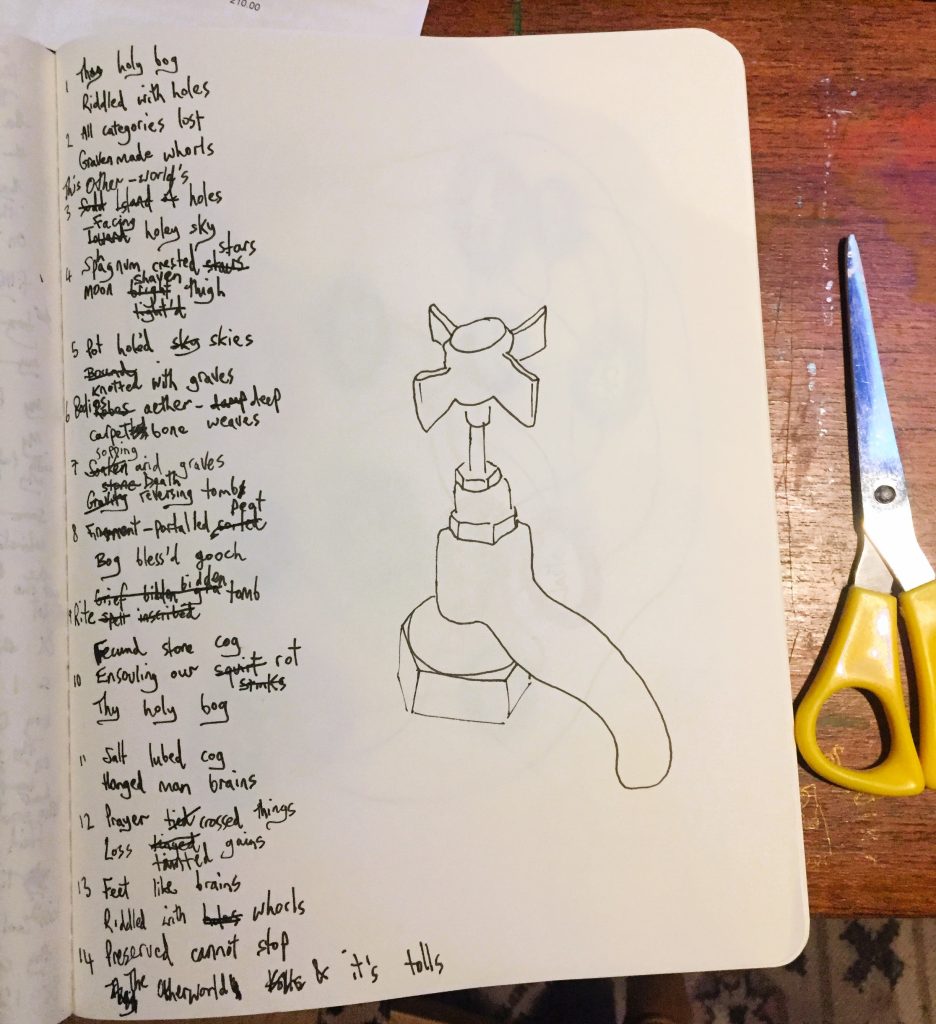

My first stab at an actual, proper, real, official, legit fourteen-lined sonnet. And it just so happens to be bog-themed. I wrote this in response to my friend Rabindranath Bhose’s work, who is currently working on a boggy solo-show which will be opening this June at Collective Gallery, in Edinburgh. Rabi and his boyfriend, Oren (who is also a super interesting artist), came to stay with us in Shetland a month or so ago. We visited lots of bogs together (including the site where the Gunnister Man was found, about a 15 minute drive from our house here), and I owe a lot of my current, reinvigorated, love of bog-lands to their visit.

So, the bog sonnet. This is where I’m up to with the edit so far (though it’s still very much a work in progress, so go easy on me!):

Thy holy bog / Riddled with holes

All categories stray / Graven made whorls

Other-World’s holes / Face holy sky

Sphagnum crusty stars / Moon shaven thigh

Pot holed skies / Knotted with graves

Bodies aether-deep / Carpet bone weaves

Sopping arid graves / Death reversed tomb

Firmament portalled peat / Bog bless’d gooch

Rite bidden tomb / Fecund stone cog

Ensouling our rot / Thy holy bog

Salt lubes cog / Hanged Man brains

Prayer crossed things / Loss borne gain

Feet like brains / Riddled with whorls

Preserved can’t stop / Other-World tolls

2022

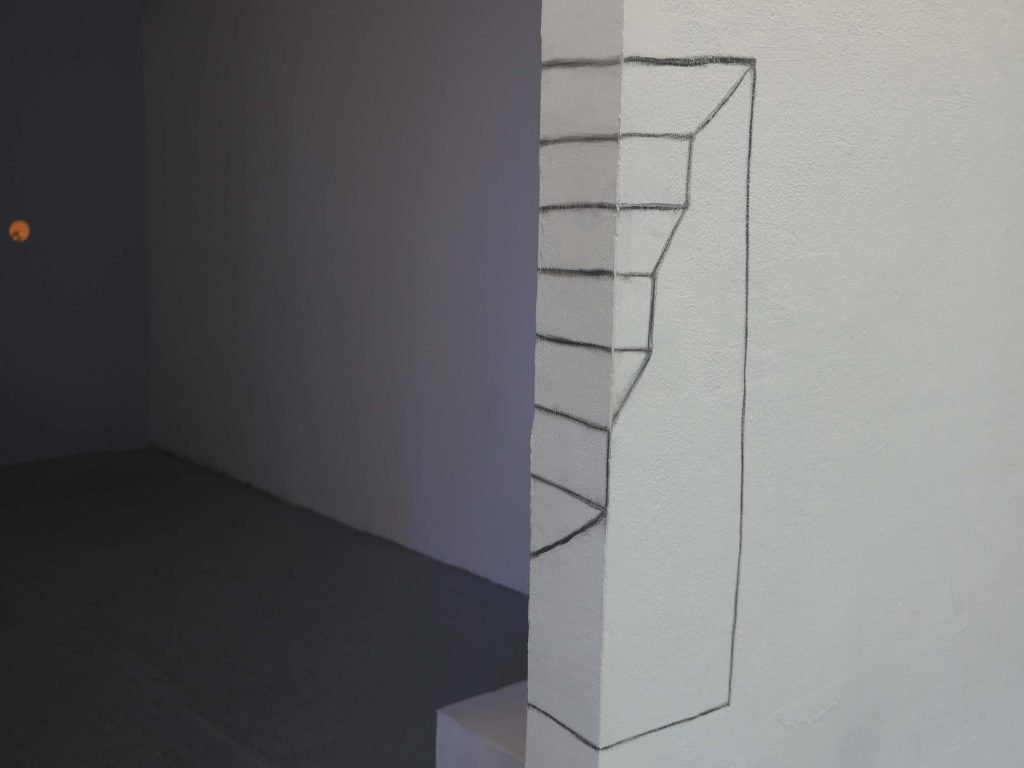

One of the installation works in project (Obstacles)

2022

One of the installation works in project (Obstacles)

Video art

2022

Third element of project (Obstacles)

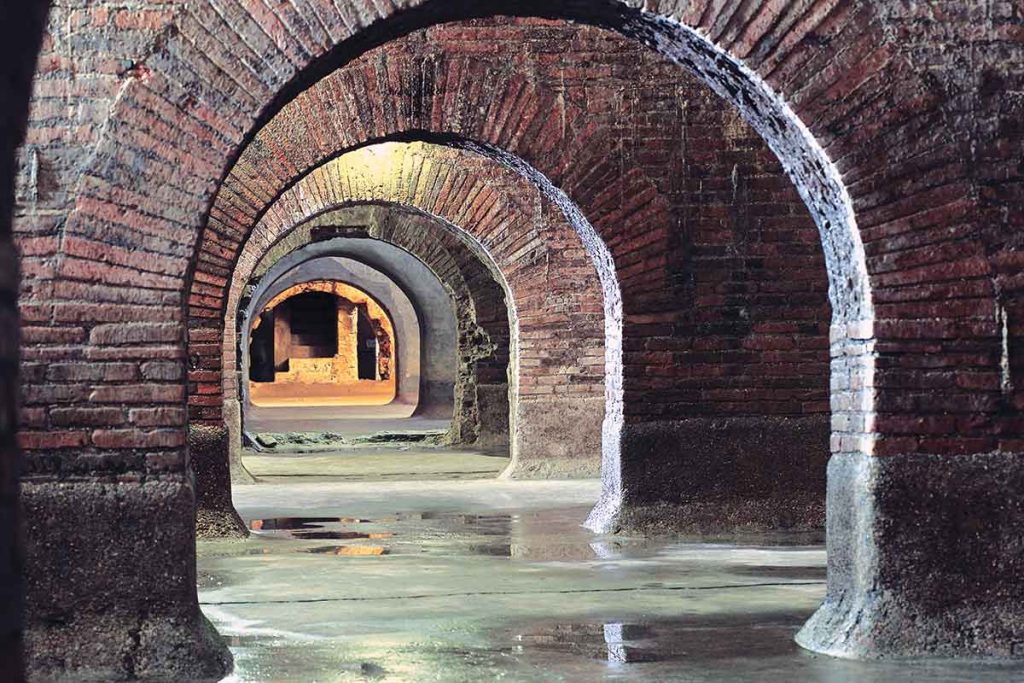

Beneath the streets of Rome lies the Cloaca Maxima (‘The Great Drain’), one of the worlds earliest sewage systems (named after the Etruscan deity Cloacina, a goddess of purity and filth). Pliny The Elder called Rome a “hanging city”, referring to the rivers churning beneath it through the Cloaca Maxima’s depths. It seems this feat of engineering was considered much more than merely a place to dispose of the city’s waste, but was a numinous and mysterious site, a literalisation of the city’s Underworld.

I came down with a cold over the last two days and so lay in bed eating soup and crisps and watching films. Two of the films I watched were Anthony Hopkins Hannibal vehicles (Red Dragon, and Hannibal), and both were pretty bad (admittedly, Red Dragon was the least bad of the two), and really showed up how Anthony Hopkins Hannibal is like a one-dimensional cartoon character, in comparison to the genuinely terrifying black hole of Mads Mikkelsen’s iteration.

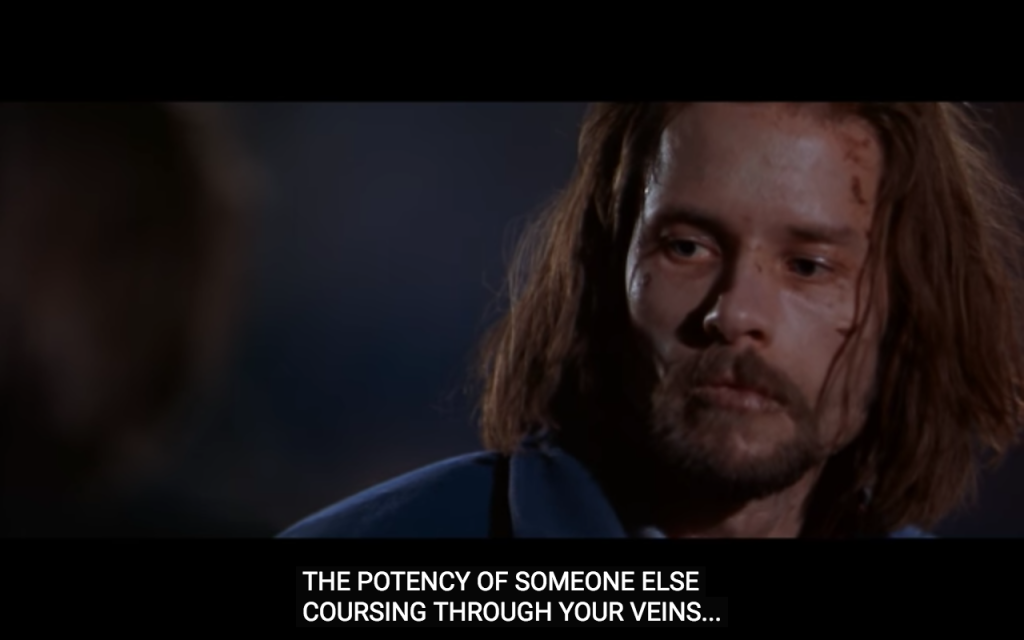

Anyway, the other film I watched, continuing the cannibal vibes, was the 1999 Ravenous, directed by Antonia Bird, written by Ted Griffin, and starring Guy Pearce and Robert Carlyle. I’d never heard of it until I listened to this podcast episode with Sasha Ravitch. The film is utterly bonkers, in a very enjoyable way, and has lots of overlaps with the classic vampire story cliche of turning people into vampires so you have someone who can actually relate to you, the desire to be seen and understood in your monstrosity, not shamed or shunned for it. It also brings in the First Nations, Great Planes, and Great Lakes indigenous folklore of the Wendigo:

“The wendigo is often said to be a malevolent spirit, sometimes depicted as a creature with human-like characteristics, which possesses human beings. The wendigo is said to invoke feelings of insatiable greed/hunger, the desire to cannibalize other humans, and the propensity to commit murder in those that fall under its influence”

Ravenous places this mythical creature as a blunt metaphor for the USA’s imperialist/colonialist expansion and consumption of people, land and resources, whilst offering an assortment of temporary boons and power to those who will exercise the nation-state’s will on it’s behalf (which in the film make the characters rapidly heal from potentially mortal wounds, and give them what Carlyle’s character repeatedly refers to as ‘VIRILITY’).

Interestingly, in the Wikipedia entry for Wendigo, Hannibal the TV show pops up again, as this is what Will Grahams hallucination throughout the series is in reference to:

![A screengrab of a quote from Hélène Cixous' The Love of The Wolf, that reads: "As sson as we embrace, we salivate, one of us wants to eat, one of us is going to be swallowed up in little pieces, we all want to be eaten, in the beginning we were all formerly born-to-eat, wolfing it down, eating like a horse; we are starved, full of whetted appetites - but better not say it, or else we'll never dare to love. Or to be loved. Love is always a little wol-f-ishy [loup-che] - a little peckish, it's not nice to say, but..."](https://vitalcapacities.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Screen-Shot-2023-04-13-at-12.56.47.png)

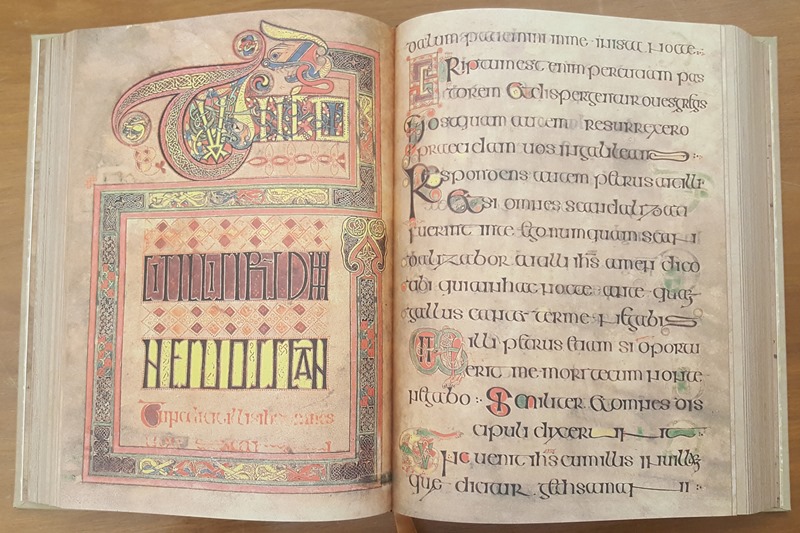

This is a kind of mock-up of something that’s been floating around my head for a minute. I’ve been crushing on illuminated manuscripts recently (particularly the 9th Century Christian Gospel manuscript The Book of Kells), and have been thinking about how to do a similar thing for a text-based adventure game (for example, here’s one I made earlier – I have no idea what the new game will be yet, but I’m trying to be ok with working in the dark about that and just following my guts). So this is it, an animated border for a game to come.

For over 5 years now whenever I start a new painting or drawing, before I put anything else down on paper, I draw some guts. It feels like they should be the foundation from which everything else is built on top of. The image of guts have become a stand-in for me that speaks to eating, digestion, shit, waste, and desire. So it feels appropriate for this to be one of the first things I make as part of the residency.

Hi Hi

Bassam here, and welcome to this space where ill be posting some WIP images of a project I’m developing with˚ʚJennifer Mehiganɞ˚ .me and Jennifer have made a lot of work in the past, some short film works and lightTM Collaborations but this will be the most ambitious of our collaborative works.

we generally use the picture below as our portrait, Jen being the horse and me being the armored figure (time for an update as i think we are now maybe both horses ???)

We made this short film/video a while ago, and its functioned as a precursor to the work we are making together now. The work explored themes of divine retribution, queendom, and climate change through the lens of Catholic iconography, constellations, and Fallopia Japonica (Japanese knotweed). Through out the work you encounter images of embracing horses, highly stylized diagrams, floating eyeballs, a dead horse, a hand growing flowers out of its palm and other convulsing plant life.

I will be using this residency to build the world of the film we are making together, so ill be posting some images of character design, landscape layouts, portraits of computer generated flowers, CG outfits among other things. ❀❀❀❀❀❀❀❀❀❀

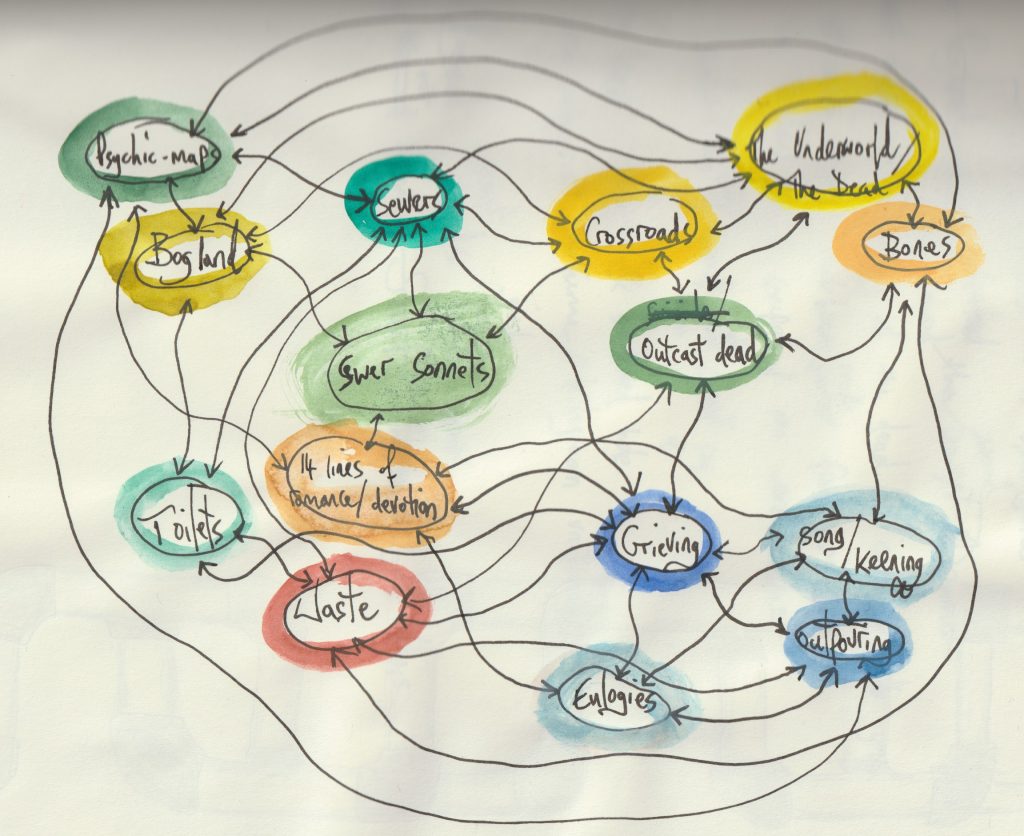

The first thing I do whenever I start a new project is draw a mind map or diagram as I find it to be a super useful way of getting a sense of where I want the work to go. And so, this is a mind map of interests I’m aiming myself towards for the Vital Capacities residency.

Looking back over it, there’s one glaring absence in this map: cannibalism. I just watched the TV show Hannibal, and am low-key obsessed (and probably permanently tainted) by it’s very gay tale of aching desire and the high aesthetics of anthropophagi (or human-eaters). To my mind, cannibalism connects nicely into the above mess of interests. There is a beautiful Buddhist food offering my girlfriend taught me, composed by Roshi Joan Halifax: “Earth, water, fire, air, and space combine to make this food. Numberless beings gave their lives and labors that we may eat. May we be nourished that we may nourish life.” Food always carries the dead with it. Of course, Hannibal accelerates his victims proximity to their death, and a number of times refers to them as no better than factory farmed livestock, so I’m not sure ‘ethics’ are high on his agenda, so much as aesthetics.

I love finding a title for a new body of work, it feels super freeing to have a banner, ‘SEWER SONNETS’, under which all sorts of ephemera can be connected and begin communicating with each other. I am really interested in how sonnets are this weirdly specific poetic form (traditionally it is a poem composed of 14 lines in iambic pentameter) that has emerged as THE genre of love poetry, and potentially even more specifically as the ultimate genre for dead lovers’ poetry.

Welcome to my studio, where I can share my practices and my experiences.

This space belongs to an emerging Palestinian artist called Shaima Sheikh Ali or “Mohammad Ali”, since the israeli colonial forced us to change the name of our family in the “israeli ID”!

My multimedia art explores the liminal space between the personal and the collective, which is a point of intersection and a point of departure. I use sculpture and video as the main elements in my installation art.

The most common challenge that artists in general and the Palestinian artist in particular, is experiencing challenges of all political, societal and religious censorship that may be imposed by the authority, in which this external censorship gradually turns into self-censorship imposed on the Palestinian self. Internal control requires deception and covering up of information we know about our real issues; this comes from the womb of truth and reality. Access to this information raises the value of freedom of expression and critical thinking.

In addition, there is a scarcity of supporting institutions, and lack of Palestinian artistic platforms, especially in Jerusalem, due to the restrictions and oppression imposed by the colonists. Parents also have power that can limit their children’s progress, and impose their control, which prevents them from taking important steps towards what they want. In addition to these challenges, physical disability also has a place, which I struggle with in particular. It’s the reason why I can’t access some exhibitions and art residencies; a situation that makes the everyday difficult, and makes the difficult impossible.

This residency will give me the platform that I need to expand my experience in order to share it with you. I am excited to be on this residency on Vital Capacities, to develop one of my techniques that I previously developed for one of my artworks.

You are very welcome to take a look around my studio, and if you have something that you want to say or to share with me please feel free to leave a comment.