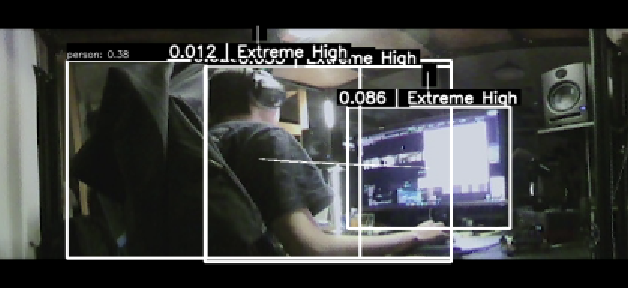

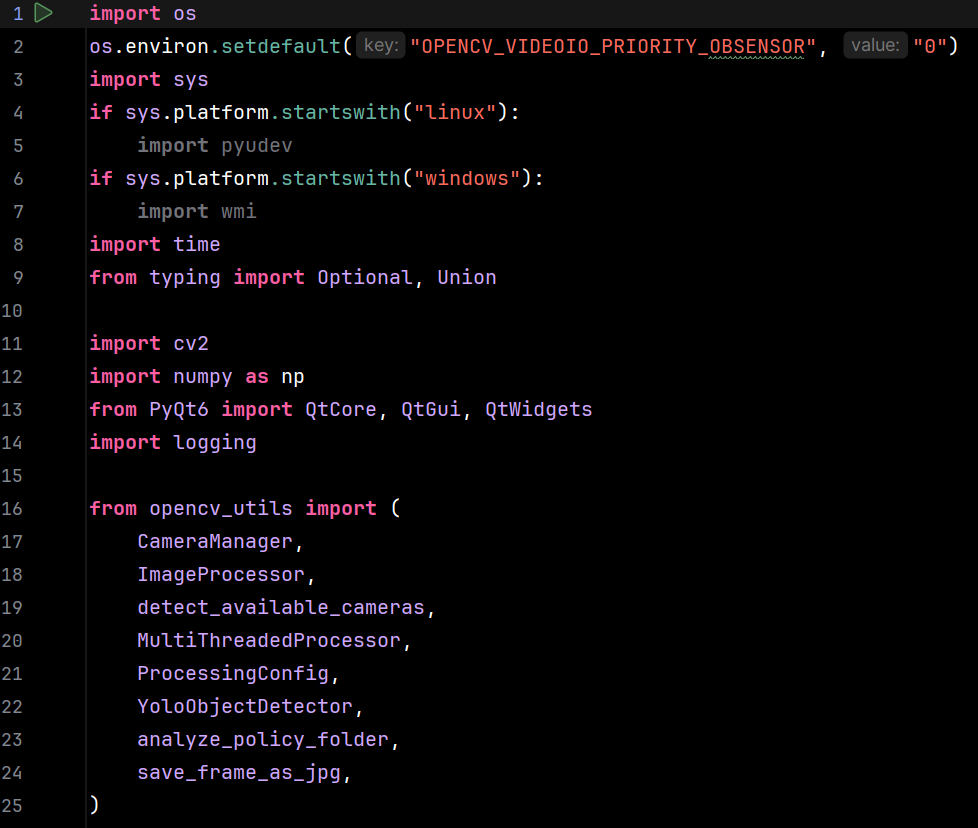

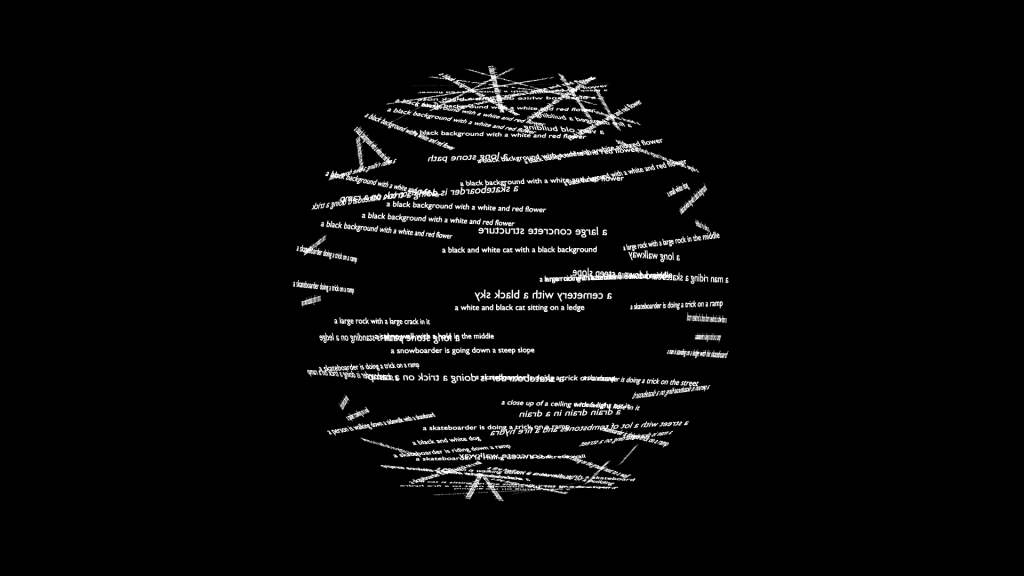

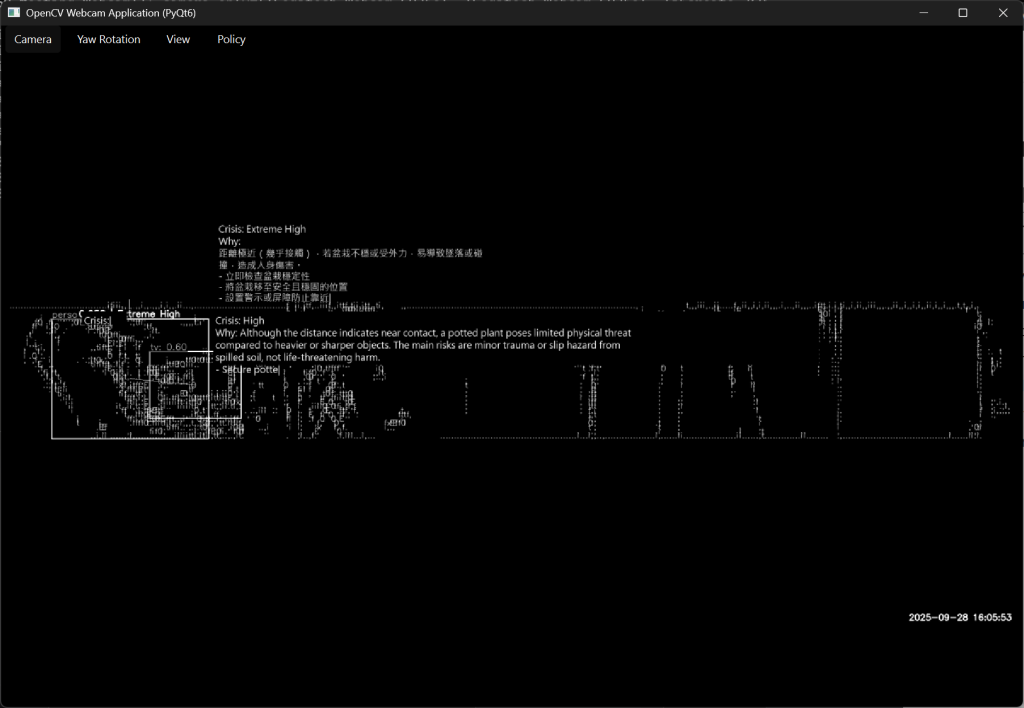

Having set up the object detection pipeline, I proceeded to the image processing stage, where the raw visual data and the model’s outputs are transformed into a more artistic representation. My process involved several key steps. First, I applied edge detection algorithms to the video frames. This technique identifies points in a digital image where the brightness changes sharply, effectively outlining the shapes and contours of objects in the scene. Next, I inverted the black and white colour, creating a stark, high-contrast visual style. Finally, I took the bounding boxes generated by the YOLO detection model and redrew them onto this processed image. This layering of machine perception over a stylised version of reality creates a compelling visual dialogue between the actual scene and the AI’s interpretation of it.