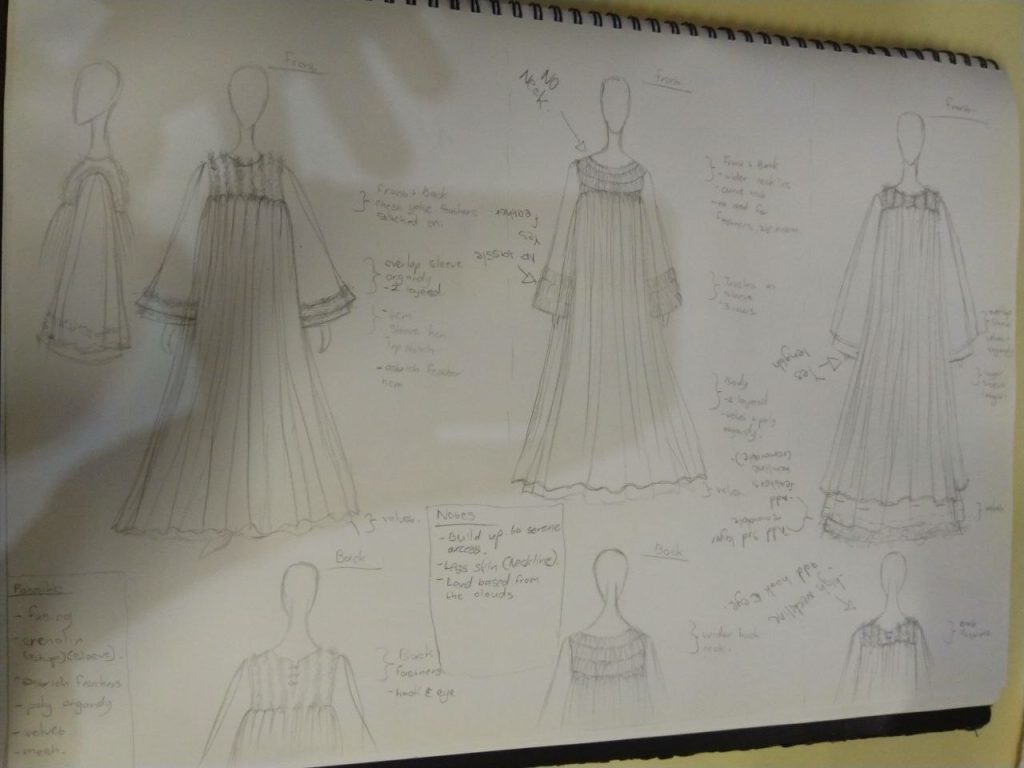

In my previous post, I asked AI to visualise the womb and this exposed an interesting bias about how the word “womb” is attributed to pregnancy, childbirth and motherhood.

I wanted to see how the results would differ if I used the word “uterus” instead. This word felt more scientific and anatomical so I assumed the imagery would look more like the organ as it appears in our body instead of the abstract image of fetuses in utero.

I used this prompt:

“a photorealistic image of the uterus“

These were the results

Image Description

A series of four images showcasing the different types of colorful human-style organs. Each photo is set against a soft pastel background that enhances the realism and detail of each organ with delicate pink veins. This visual representation highlights both scientific precision while also conveying an emotional connection through its vibrant colors.

Just as I expected. Using more scientific language gives us more scientific results that do not carry the bias of the womb or uterus being used for childbirth. But one thing sticks out to me…It hasn’t quite depicted the uterus accurately. They sort of look like non-descript abstract human organs. The last one looks like a heart. This is further proven when we look at the raw results of Midjourney trying to describe the imagery it created.

See below:

A series of images showcasing the anatomy and structure of different types of colorful human organ, such as heart, buds, Game design style, Zbrush rendering. It is rendered in high resolution using Octane Render with a 3D render engine. The lighting effect adds depth to each scene. In one part there’s an illustration of two ram horns. In another there is an illustration of many pink flower petals floating around the red root system of these flowers. All four parts are shown side by side.

A series of images showcasing the anatomy and structure of different human organ types, such as heart or bowels, rendered in realistic 3D graphics. The composition includes close-ups on individual lungs to highlight their unique features and textures. Each photo is set against a soft pastel background that enhances the realism and detail of eachorganshaped with delicate pink veins. This visual representation highlights both scientific precision while also conveying an emotional connection through its vibrant colors.

4 different views of the organ heart in hyper realistic style

Create four images of realistic human anatomy, each depicting different types of biological structures such as the heart and living arteries. Each photo should showcase intricate details in high resolution. The first image is of two beautiful female hearts made from plastic, the second one shows three living veins with red veins, the third has five white brain cells, and the fourth picture features pink flowers growing on an ear. All photos have a blue background.

The organs mentioned in the image descriptions include the heart, bowels, lungs, arteries, and brain cells.

Not one mention of a uterus. Strange.

Perhaps next time I need to make more specific prompts or this exposes that Midjourney has difficulty generating the uterus accurately without the bias of childbirth and pregnancy included.

This is not the overall aim of my project, so I will pause my experiments here. Nonetheless, it’s been eye-opening to see the gaps in how AI views the human body and in turn how we view our bodies.

![A screengrab of a quote from Hélène Cixous' The Love of The Wolf, that reads: "As sson as we embrace, we salivate, one of us wants to eat, one of us is going to be swallowed up in little pieces, we all want to be eaten, in the beginning we were all formerly born-to-eat, wolfing it down, eating like a horse; we are starved, full of whetted appetites - but better not say it, or else we'll never dare to love. Or to be loved. Love is always a little wol-f-ishy [loup-che] - a little peckish, it's not nice to say, but..."](https://vitalcapacities.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/Screen-Shot-2023-04-13-at-12.56.47.png)