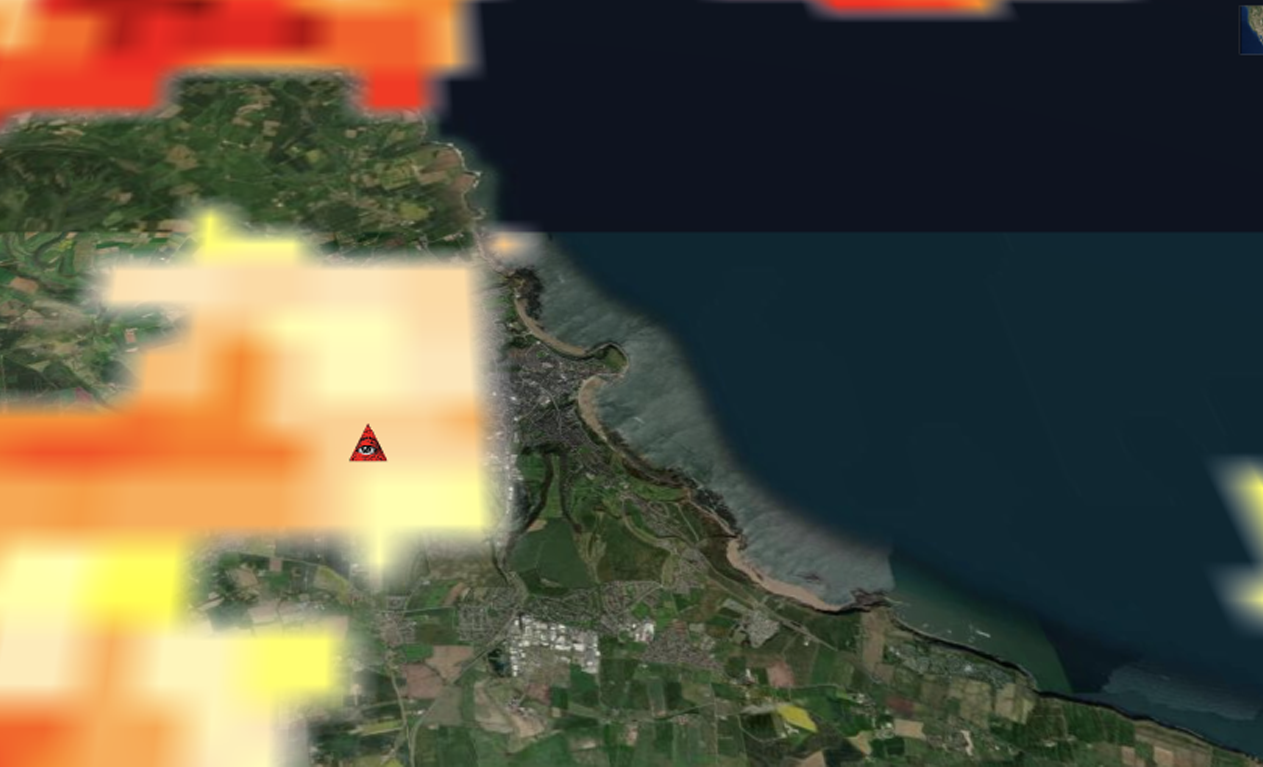

For a new online work, I’m creating a radar visualisation in which each of the dots will be assigned an image and text that reads ‘I AM NOT TARGET PRACTICE’.

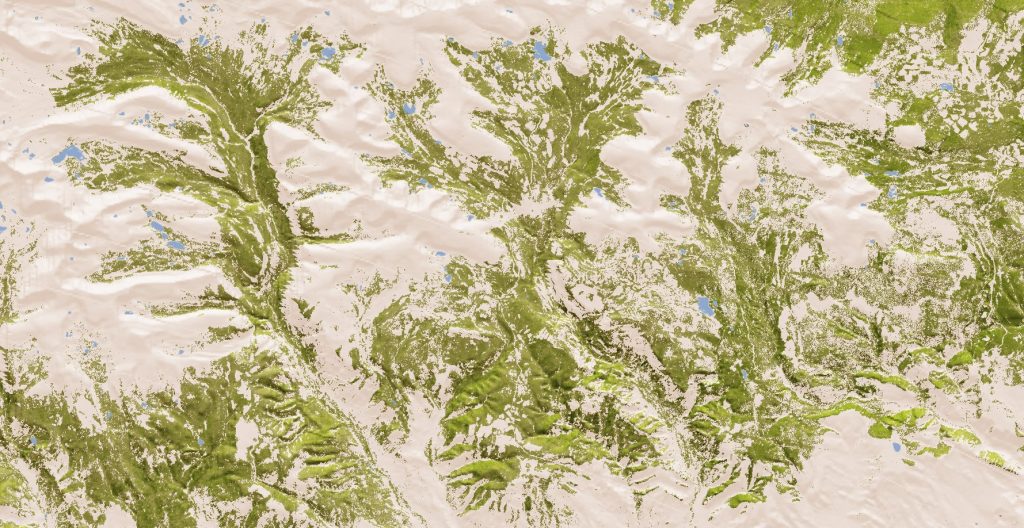

The images that I’m hoping to incorporate are of cloud data centres run by AWS, Google, Microsoft, IBM, and Oracle. I took screenshots using imagery from the ESRI satellite and focused on the data centres in Virginia because it has the highest density of such places in the world.

I’m planning on overlaying these images with cloud satellite imagery so the view of them is partially obscured.

(Alt text for image gallery: satellite imagery of data centres, many are angular and white with fans mounted on the roof).