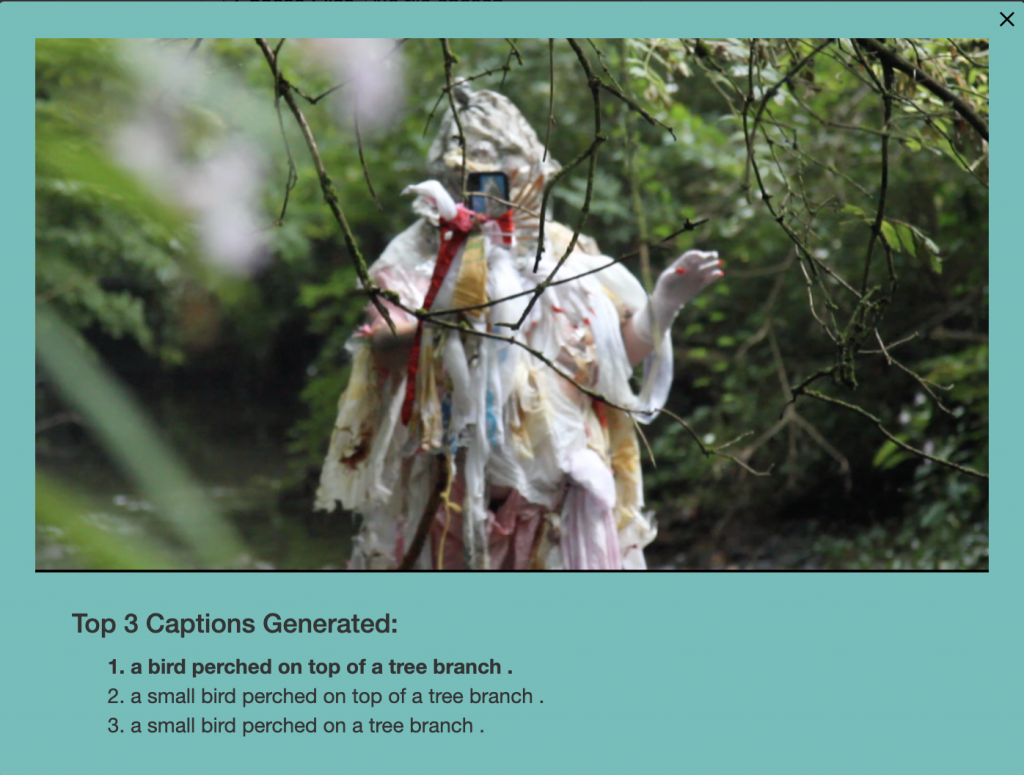

Remember when the Google glass came out years ago and ended up being not so popular? At the time, I wasn’t aware that the product had been designed to include the function of Live Captioning; while researching this I found this video of the product being used in a quiet setting.

There are many great resources you can use to transcribe speech to text on apps/browsers online. These resources work by either turning on the live transcribing function or uploading prerecorded audio files – a few I have used in the past are Webcaptioner, Google Transcribe App, Descript. (Each mentioned names are all hyper-linked which will lead you to its own websites)

Continue reading “Future of Live Captioning”

As someone who has to catheterise themselves regularly, due to my disability, I’m understandably quite into anything related to piss and urinating. I often use cardboard hospital bedpans in my work and simulate pissing in live performances.

A pissing contest or pissing match, as many probably already know, is an idiom that describes a situation where two or more people are competing with each other to show superiority, usually pointlessly.

I was happy to discover that pissing contests also exist in a literal sense where participants compete to see who can piss the longest, farthest, highest or most accurately. There are even Guinness World Records held in the sport. A woman in Italy is the current world record holder for the farthest piss created a 30 foot golden arch, although I can’t find her name.

Not only that, during combat, lobsters accompany their largest blows with a large squirt of piss out of their faces. Their bladders are located in their heads and they have nozzles under their eyes and antennae, where they release urine to communicate during mating or fighting.

When watching films, I have often paid attention to subtitles that show sound effects such as:

![Cropped image of film only showing the subtitle that says [Vehicle pulling up]. Behind the subtitle you can see cropped image of wooden table with paper stacks on it.](https://vitalcapacities.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Screenshot-2021-06-08-at-09.26.28-1024x209.png)

![Cropped image of film only showing the subtitle that says [clock ticking]. Behind the text, there's blurred shape of someone's shoulder wearing a suit.](https://vitalcapacities.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Screenshot-2021-06-08-at-09.26.55-1024x208.png)

BBC Academy has online guidelines for subtitles that would be shown across its platforms. I found this line interesting under the Music and songs section – “All music that is part of the action, or significant to the plot, must be indicated in some way.”

Description of music can prepare us for what is about to happen in a film – examples of this are subtitles such as EERIE INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC PLAYS, TENSE MUSIC PLAYS, SUSPENSEFUL MUSIC PLAYS. It can also tell us what the person is feeling – such as HEROIC MUSIC, DRAMATIC MUSIC SWELLS, SENTIMENTAL MUSIC.

I recently watched the well-known 1982 film Blade Runner, during which I noticed that while dramatic music was played, it was shown as (***) – how does (***) convey the atmosphere of the music that is being played? There are cases where the subtitle can be clever with showing context but its importance can be easily neglected.

Regulations for closed captioning started to be introduced in the UK in the 1990s to make video content accessible for d/Deaf and hard-of-hearing people. Whilst in the USA, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed in 1990, following which the majority of network providers of programs had to contribute part of their income on captioning to ensure access to verbal information on televisions and films. In 1993 with the Television Decoder Circuitry Act of 1990 going into effect, TV receivers with picture screens that were 13 inches or larger that were imported in the US had to have built-in decoder circuitry to show closed captions. Decoders used to be sold for $250 at Sears in the 1980s which meant they were not very accessible for some people. Closed captioning started out as an experiment intended only for people who were deaf, yet it became something of an everyday commodity that helped millions of people to connect. A brief history of CC can be found here.

When I was younger, I remember renting VHS tapes from Blockbusters with my family. Specifically, I remember trying to select ones that had the CC logo on them to ensure that I can watch them without worrying. Fast-forwarding to 2021, unfortunately, not all 100% of UK TV shows/films and online video services have subtitles. The UK charity The Royal National Institute for Deaf People (previously known as Action on Hearing Loss) currently has a campaign called Subtitle It! which has been tackling the issue since 2015.

There is still a long way to make existing/future web content fully accessible for everyone- but I am glad there are resources that we can learn from regarding accessibility.

I’m interested in why some sports are considered posher than others or more worthy of being featured in large sporting events.

I can’t understand why basketball dunking competitions aren’t in the Olympics. Not that I really like, care about or follow the limpics, but I feel strongly that dunking is underrated in comparison to other sports.

Dunking is an impressive and breathtaking combination of long jump, high jump, basketball, gymnastics and choreography. I could watch the high-definition slow-motion replays on Dunk League for hours. I wish they’d make another series.

A long-term enthusiasm of mine is mascot costumes. I have a collection of images on my laptop and phone of my favourites. I especially like Tweety for reasons I will explain in a later post.

I like mascots because they are a non-athletic and often surreal comedy presence in an atmosphere which is otherwise very focused on sporting physical ability. Their bodies are so jarring and out of place in these arenas of polished flexing muscles. They are often wrinkly, misshapen, oversized and furry. Anonymous. ANONYMOUS. Hiding in plain site. Now there is a sporting body that I can relate to.

They sometimes race each other to raise money for charity and dance to motivate the crowd (especially in the US), but the focus is still on the humour of their costumes and characters. Most are animal or human-like characters but my favourites are the more surreal choices like, Boiler Man of West Bromwich Albion and the angry looking sunburst, Kingsley, for Partick Thistle, both pictured below.

Head over to my studio to see some more mascot oddy-body memes I made, like the one at the top of the page.

Glass / Glas by Bert Haanstra (1958) is a short documentary that playfully shows the process of glassmaking. This is a compilation of stills featuring hands from the video for visual inspiration. I always have been interested in the movement of hands as they can give a surprising amount of information regarding one’s culture, emotions, and the context of the conversation that is taking place.

Thanks Laura Lulika for the reference!

I find the theatrics of men’s footy and ‘time-wasting’ simultaneously irritating and comical. It’s not surprising that in the less popular and historically less lucrative Women’s footy, the players spend less time pretending to be hurt.

The performance of ‘being fouled’ reminds me of the need to perform disability in certain situations. This is something that we shouldn’t have to do but are sometimes forced into so that we are considered worthy of the care we need. Of course the circumstances and reasons are wildly different to the multimillion pound ‘beautiful game’ but the ridiculousness isn’t so far apart.

In a system that is constantly trying to catch you out and take away the very limited and basic support and care you’re entitled to, sometimes you have to show them what it’s like on your worst day. The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is known for spying on disabled people and wrongly accusing them of fraud, taking them to court, siezing their property, rejecting appeals for support in their unfair ‘Fit to Work’ assessments and causing thousands of deaths of sick and disabled people every year. Sick and disabled people live in fear of being not disabled enough or the wrong kind of disabled. Either too scared to apply for any support in the first place or living in fear of having their support taken away.

I wonder, what do we have to do to be believed? Should I throw myself on the ground and weep in front of you, my face in my hands, grasping at every part of me that hurts? It’s foul!

When I was researching subtitles, I was surprised to learn about the vocabulary of Closed Captions and Subtitles.

Closed Caption is for viewers who cannot hear audio and includes sound effects.

The subtitle is for viewers who can hear audio but cannot understand the language and does not include audio effects.

Most countries outside the USA and Canada tend to merge the two words into one in film and media which explains why I found it confusing!

I also found that Open Caption means it is permanently embedded into the video itself- so it cannot be turned off by the viewer, but that means its style/size/colour can be determined by the creator ahead of time.

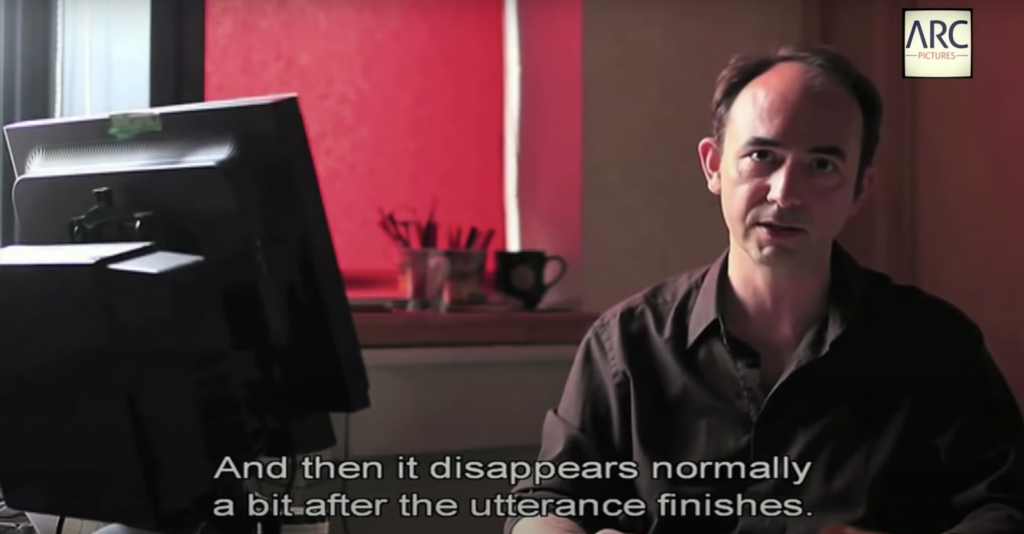

Continuing my research, I watched a short documentary called The Invisible Subtitler made in 2013. The documentary discusses the importance of the role of translating subtitles into different languages for films. It is available to watch on Youtube.

The act of translation always fascinates me as one always has to take everything into context to make the best translation. When I was learning English for the first time, I had to memorize definitions of new English words in Korean words. As I learned more about English, I realised that one English word does not always have a single Korean word when translated.

Like language, sound can also be translated in many different ways. In subtitles, the sound can be summed up into a single word or detailed description. It depends on the choice of subtitler or scriptwriter. There are times when the subtitle can just show as (MUSIC) or it can be showing in details such as the title of the music and its lyrics.

Yesterday I enjoyed spending the day exploring archival film footage found at London’s Screen Archives. One thing I have noticed during my research so far is the abundance of content – it’s great to see that so much is readily available. For the next few days, I will continue exploring the collection to get inspired for the visual research.

If there’s any suggestions or references I could research regarding subtitles, please let me know!

Did you know that when you look up synonyms for the word ‘athletic’ it suggests; ‘frail, weak, infirm, delicate’.

Antonyms include, ‘muscly, well built, strong, fit, healthy’ and… ‘able-bodied’..

As if to suggest that disabled people could not also be athletic or hyperable at the same time, that they are mutually exclusive. Of course we know this not to be true but we rarely see examples of this in mainstream media, unless it is for inspiration porn.

This is why I have chosen to use the term, ‘hyperable’ instead of the word ‘athletic’. Too often this body type is considered the norm, the average or what is considered ‘healthy’ in our Western society and media. Everyone else’s experiences of their body, who don’t fit into this category, are somehow deemed less than. I want to highlight, through the language and terminology that I use, that all body types are of course valid and that being athletic or hyperable is a choice to push your body into a form that is in most cases, beyond what is necessary to survive. You have made yourself, in some way, ‘hyper-able.’

Bodies are more complicated than the binaries of athletic or weak, fast or slow, healthy or unhealthy. They are soft and leaky, strong and vulnerable, uncooperative and reliably inconsistent. They contain emotions and memories. We can adorn them with the symbols of who we are and connect with ourselves and others through them. Where are the celebratory arena sized events for these bodies? The non-normative normal bodies.

Besides, the word athlete comes from ancient Greek words that mean, ‘one who competes for a prize’ so in some sense we can all be athletes if we really want to be. I won a goldfish on the fair once.

spit bubbles on finger move in and out of clarity

Finger glows red, slightly

partner says ‘hi Little Cat’ offscreen

Image Description: Watershed

Linda Stupart Watershed 2020, video, 11:06

Image Description by Aubree Penney

Image Description

Clad in black galoshes, a person wades into a small, murky river, past an abandoned shopping cart that lies in the water nearby. The person’s outfit consists of pink, yellow, baby blue, and lavender tie-dyed pieces and bits of pink pastel plastic. The arraignment drips behind them, dragging the ground, covering their head like a hood in a cheerily chaotic hodgepodge of pastel bits and pieces. Bright yellow tie-dyed gloves are on their hands. Lush greenery surrounds one side of the river, with tangles of roots emerging near the waterline.

They walk away from the camera towards a brick bridge with two arches, circles of water rippling out from their feet with each step.

Splashes of water accompany each of the figure’s steps, as the chitterings of birds mix with the rush of passing traffic and the light whisper of wind.

A warm, welcoming voice off-screen layers over the background noises of the river:

Ok, so, everyone close your eyes. Ok. So, now that your eyes are closed I want you to really think about the spit that’s in your mouth. So like everyone has spit in their mouth. Just be really aware of that spit in your mouth.

Ok, so you’ve got the spit, it’s there, it’s in your mouth. Now what I want you to do is imagine that there’s a cup in front of you. You’ve got a cup, it’s empty, maybe it has some water in it. It’s in front of you. Now, I want you to think and imagine spitting that spit out into the cup in front of you. Ok. Cool. Now that you’ve done that, I want you to pick that cup up and drink that spit back into your mouth again.

The camera dips into the water, revealing a tumult of sticks and dirt, decomposing leaves, and a white strand.

The camera shifts angles, revealing the figure emerging from beneath the brick bridge. A stone wall with trails of ivy meets the bridge at its top, containing the river, with a wealth of greenery emerging from the damp land at the river’s far edge, piles of stones and debris on the bank nearest the camera. The river narrows to only a few meters’ wide.

On screen text beneath the figure reads: The long arm of the law was in full evidence when police were called to reports of a human limb floating in a Birmingham river.

Splashes accompany the slow, steady movement of the figure in the water as the birds continue to sing.

On screen text beneath the figure reads: And the officers went further out on a limb after they struggled to get out of the river – providing amusement to those watching the operation to retrieve the wayward body part.

The voice off-screen clears its throat, which echoes slightly, before beginning to sing Black Sabbath’s “Electric Funeral.” The pace is slow, lingering, sung in a rich middle range and lending a haunting air. The song clings to your skin, subtle but insistent. The sounds of the riverbank continue in the background, the twittering of birds lightly piercing the darkness of the sung melody.

The voice sings:

Ba, ba da nuh nuh, duh nuh nuh, duh nuh nuh, ba ba

The gurgling of the river replaces the sound of birds as the camera dips into the water.

The camera plunges and twists beneath the water, revealing dirt and detritus in the grayish water and offering momentary glimpses of the figure’s pastel robes, stirring bubbles beneath the water and a blue sky above streaked with white clouds.

Our view shifts back to the figure, slowly proceeding along the river. A black and white image of an arm layers over the left side of the image. The arm is wrapped in something at the elbow, the skin looking mottled and patchy. The hand is outlined in yellow, raising it against the screen. Behind the picture of the hand is a vertical video hovering over a container of orange goop with bits pressed into it. The video of the orange goop disappears. In the center, beneath the black and white hand appears the image of a blue-gloved hand holding a white, stuffed glove with blood on its fingertips in front of a river with rocky banks and lots of trees around it.

The figure approaches a small waterfall.

The camera shifts to the top of the waterfall. The black-and-white hand image disappears, shortly followed by the disappearance of the image with the stuffed glove.

The figure clambers over the falls and stands at the top, revealing in their hand a Y-shaped wooden diving rod, with orange string and a small camera at the top. A tattoo peeks out just beneath their right elbow.

The voice continues to sing:

Reflex in the sky-y warn you you’re gonna di-ie

Storm coming, you better hi-ide from the atomic ti-ide

Flashes in the sky-y turns houses into sti-ies

Turns people into cla-ay, radiation mines deca-ayyy

The voice emulates a guitar interlude, the sound becoming increasingly sharper and more insistent:

Dee da na now, de duh na now, do do duh na now, dee dee nuh nee, duh duh da now, dee dee nuh nee,

Bow bow buh na now, duh nuh nee

Robot minds of robot sla-aves

Lead them to atomic ra-age

Plastic flowers, melting sun

Fading moon falls apart

Dying world of radiation

Victims of mad frustration

Burning global oxy’n fire

Like electric funeral pyre

The figure continues their journey, the waterfall now behind them. They reach down and grab a long, thin branch, untangling it from their clothes. They toss it behind them, the branch eliciting a small spray as it smacks the water.

A light splash joins the sound of the figure wading as they throw the stick in the water.

Duh da na now, de nuh na nee, ba ba da nuh, dee nuh na nee

Ba bow duh na now, nuh nuh na

The figure progresses between two piles of sticks in the river, speckled with castoff bottles and other pieces of rubbish.

The voice transitions to the rhythmic, airy flicking sound of a tongue flicking the top teeth, steady as the second hand on a clock. The rhythm continues, now comprised of gentle, insistent tapping sounds that have the steady rhythm and assuredness of a warm rain on skin.

The camera dips beneath the water, revealing murkiness and the pinks of the figure’s robes once more as well as the verdant edges of the bank.

As the camera dips under, the gurgling rushes of the river return.

An inset box, framed now by murkiness, reveals the figure navigating under and around a low canopy of branches that are over the river. A fingertip briefly slips in front of the camera lens.

The high-pitched bird songs return as the tapping fades.

The background image shifts to the figure wading towards the camera. In the foregrounded image, the figure trips on a branch and slowly falls into the water. They slowly sit up and begin to remove their mask.

A deep, startled exhale as a branch snaps, followed by a slow splash.

The airy rhythm returns, a ticking made of breath, tongue, and teeth, quickly switching to the drumming of flesh against a surface. The drumming grows louder, softens, and then abruptly halts.

The image cuts to a skinned knee with blood dripping down, leaving rust colored trails behind on the pink skin, the damp pink, yellow, and light blue fabric hanging about the hurt leg. The camera twists, revealing a tattoo beneath the skinned knee, now black lines merging with light pink streaks of blood as the blood drips past the tattoo and down into the rainboot.

A soft voice, the slight kiss of breeze brushing past is audible around them:

Thank you

All sound ceases.

The camera pauses on the figure’s head, covered in a gray and pink floral mask with huge half-sphere eye pieces of clear plastic. Bits of lavender and laminated fronds are revealed to be part of the ensemble. The figure’s right hand wears a yellow tie-dyed glove and holds the diving rod aloft. Bits of orange yellow, white, and pink string adorn it, mixing with wires and buttons for technology and a laminated paper that reads “Deriving from the Latin word vulnus [wound], vulnerability expresses the capacity to be wounded and suffer. As bodily, social, and affective beings, we all have the capacity to be vulnerable to one another and to conditions of inequality, discrimination, exploitation, or violence, as well to the natural environment. The next sentence is crossed out.

The sloshes of the water and bird songs return.

The figure proceeds onward down the dirt bank beneath an organically formed archway of trees and bushes. Tiny, lacy white flowers dot the ground to either side of the dirt path.

The off-camera voice speaks:

Scum on the top of the river, skin on the top of milk, skin on the top of the river, scum on the top of milk. The River Cole is constantly threatening to flood like I am, like we are.

[a deep breath]

Superimposed on the screen is a collaged tangle of daisies, leaves, yellow and green slivers, a cacophony of soft angles and cheery natural hues. Behind the collage, the figure steps back into the river and proceeds on their journey, greenery visible on both sides of the water.

The limb, the Cole’s River limbs flailing upstream towards her mouth and her teeth. When you drink a glass of water you also drink its ghosts. When you piss in the mouth of the river, your wastes embrace her pasts.

The image of the blue-gloved hand holding the stuffed white-gloved hand in front of the river is superimposed over the collage.

Do keep body movements minimal. Do move and gesture slowly and naturally.

The superimposed images disappear, giving a clear view of the figure wading in the river, their divining rod in their right hand.

Do maintain eye contact by looking straight in the camera.

The collage of leaves and daisies and ephemera and the image of the blue-gloved hand holding the stuffed white glove in front of the river are superimposed over the figure’s journey again.

Bodies and the law are diametrically opposed. And the power of the police and/or men comes from somewhere else from flesh or bone or viscera, rather from unwoundedness, calcifications, non-porous materials.

The collage disappears. The superimposed image of the stuffed white glove shifts to a video showing reflection on the water’s surface and then scum at the bottom of the river, a glimpse of the divining rod, then more brown debris and dirt beneath the water.

The virus sits on these materials but does not penetrate them. Rather, she waits. Scum on the top of the river, skin on the top of milk, as the river flows, it picks up sediment from the riverbed, eroding banks and debris in the water. The river mouth is where much of this gravel, sand, silt, and clay is deposited.

The superimposed video disappears, leaving only the figure in the river.

The haunting song interjects:

Turns people into cla-ay.

On-screen text at the top of the page, in white text atop an image of river water: the police hate water because it does not obey the law

Immediately the singer transitions back to speech:

The police hate water because it does not obey the law and because they cannot swallow or incorporate her.

The on-screen text disappears. A black and white image of a right hand, marked with red bits and globs of ooze, a bit of red flakiness at the center, appears in the bottom right corner. The hand is surrounded by a thick yellow line.

Kill the cop in your head to lose your tongue and exit language, swim in the blue lagoon now dyed black, let algae stick to you and stop holding hands.

The image of the oozing hand disappears. The figure has almost reached the limits of visibility for the camera and glances back quickly, then proceeds onward.

Cling to the viscera in your head, kill the cop in your high-wage, high-skill, high-productivity economy.

The Prime Minister says he does not care if you die, but that is because he does not understand that the dead are still a threat to him and to the law. When you drink a glass of water you also drink its ghosts. When you piss in the mouth of a river you also come in her pasts.

A path of spaced stones spans from one bank to the other, forming a walking path. A huge, decaying log sits to the right. Water flows between each stone, forming tiny waterfalls as the water changes levels by a few feet. The camera gets closer and closer, revealing moss on the stones of the path and the foam at the bottom of the miniature waterfalls, and begins to cross the river.

The water rushes in the background, a gentle but ceaseless torrent of sound.

The haunting song interjects, gaining speed and urgency:

Rivers turn to mud, eyes melt into blood

A wobbling clip of tan eggshells on the dark riverbed is superimposed atop the pathway of stone and waterfalls.

The mouth of my mouth and the spit of the river.

The camera swivels at the center of the river, revealing the figure slowly proceeding towards us, flanked on either side by tall trees and lush tangles of small white flowers. Birds dart across the river, making ripples as they touch down, and a huge limb lies in the midst of the water.

I am meters away from you and in the river holding my breath and still sucking up your sediments discharging foam and teeth.

The video of the bloody knee, surrounded by pastel swaths of the figure’s attire, is superimposed atop the river scene, framing the knee with greenery and rippling waters.

Foam on the water, sign of life and death.

The virus and the river water slither down policemen’s teeth or cheek, resides there. The mouth becomes the source, becomes the rapid and the edge.

The superimposed image disappears.

You find the bones of children sometimes, soft hands on necks or weeds tangled between toes and mud and stinking flesh. Amniotic fluid often spills before it breaks, and sometimes fishes also die, she said, as eggs come tumbling onto scales and gills and mammalian hair on legs.

A video of the figure kneeling in the water, holding their masked head with their left hand and dipping their divining rod into the river with their right. A white stuffed glove is visible next to the rod. The figure slowly moves the rod in the river, its strands of fabric and ephemera floating, shifting with the motion of the rod and the current.

Eggs are always a disaster or a triumph, like the river and your viscera, or the virus and the sea.

The superimposed image disappears. The figure uses the rod for stability as they continue towards us, navigating around the branch in the midst of water.

Do keep minimal straight body naturally across the path to keep the other and the virus safely out and maintain body and maintain eye appeal to the warm contact camera contact nature keep slowly looking straight into the body.

The haunting singing emerges from the background, so soft as to be nearly indecipherable. It hovers in the back of the mind of the video. It sings:

And so in the sky shines the electric eye

Supernatural king takes earth under his wi-ing

The speaking voice off camera continues, edges of phrases and sentences blurring and piling upon each other in a near breathless torrent of words:

There caught in the elbows of fallen trees are curving mounds of white foam. Police are called about a water in the body and a body in the water or the river found dead across the edge or bursting skin cells multiplicities and masks and balls at the end of your arms at the end of the ball at the end of nothing. Rehabilitation of the riverbanks are getting better, but what if we never get better or go freckles forward, but what if we never get better or go forward but circle around rather in and out.

The water grows deeper as the figure nears the camera. The figure’s steps become more tenuous, deliberate as the water reaches their thighs. They sink down with the divining rod, the water level up to their chest.

The volume of the song in the background swells. It progresses still at a slow, haunting pace, but feels bolder, more confident, less content to linger:

Heaven’s gold chorus sings

Hell’s flap their wi-ings

Evil souls fall to hell

And they’re trapped in burning cell

Da na now, da da na now. Doo duh da na now, da na na now. Da na now, da na na. Duh nuh nuh, Buh buh na na,

The figure leans back, immersing themselves entirely. The screen goes black.

The sound of rushing water in the background abruptly ceases, leaving only the singing voice to continue with its interpretations of Black Sabbath’s guitar.

A white text box appears on the black screen. It reads:

PART 1

Shot on location in the River Cole (Sparkhill – Hall Green)

Filming by Tom Dillon

Song by Black Sabbath

A beat picks up, both in time to the rhythm of the syllables being sung, recalcitrantly deviating at others.

Doo doo do-do, doo doo do-o

Buh buh buh, buh buh-a

Buh buh na na

Duh Duh duh now

Buh buh buh, buh buh-a

The white textbox disappears, leaving only a black screen.

The beat increases in speed, becoming a frantic heartbeat for a few seconds before disappearing entirely.

The song continues softly:

Buh-a. Duh na. Duh na.

Barely audibly, the voice concludes, still on pitch and beat with its song, leaving us with a gentle, hovering syllable:

Mmm

Sound Transcription: Watershed

Linda Stupart Watershed 2020, video, 11:06

Sound Transcription by Aubree Penney

A warm, welcoming voice off-screen:

Ok, so, everyone close your eyes. Ok. So, now that your eyes are closed I want you to really think about the spit that’s in your mouth. So like everyone has spit in their mouth. Just be really aware of that spit in your mouth.

Ok, so you’ve got the spit, it’s there, it’s in your mouth. Now what I want you to do is imagine that there’s a cup in front of you. You’ve got a cup, it’s empty, maybe it has some water in it. It’s in front of you. Now, I want you to think and imagine spitting that spit out into the cup in front of you. Ok. Cool. Now that you’ve done that, I want you to pick that cup up and drink that spit back into your mouth again.

Splashes of water accompany each of the figure’s steps, as the chitterings of birds mix with the rush of passing traffic and the light whisper of wind.

The voice off-screen clears its throat, which echoes slightly, before beginning to sing. The pace is slow, lingering, sung in a rich middle range and lending a haunting air. The song clings to your skin, subtle but insistent. The sounds of the riverbank continue in the background, the twittering of birds lightly piercing the darkness of the sung melody.

The voice sings:

Ba, ba da nuh nuh, duh nuh nuh, duh nuh nuh, ba ba

The gurgling of the river replaces the sound of birds as the camera dips into the water.

The voice continues to sing:

Reflex in the sky-y warn you you’re gonna di-ie

Storm coming, you better hi-ide from the atomic ti-ide

Flashes in the sky-y turns houses into sti-ies

Turns people into cla-ay, radiation mines deca-ayyy

The voice emulates a guitar interlude, the sound becoming increasingly sharper and more insistent:

Dee da na now, de duh na now, do do duh na now, dee dee nuh nee, duh duh da now, dee dee nuh nee,

Bow bow buh na now, duh nuh nee

Robot minds of robot sla-aves

Lead them to atomic ra-age

Plastic flowers, melting sun

Fading moon falls apart

Dying world of radiation

Victims of mad frustration

Burning global oxy’n fire

Like electric funeral pyre

A light splash joins the sound of the figure wading as they throw a stick that was in their way behind them in the water.

Duh da na now, de nuh na nee, ba ba da nuh, dee nuh na nee

Ba bow duh na now, nuh nuh na

The voice transitions to the rhythmic, airy flicking sound of a tongue flicking the top teeth, steady as the second hand on a clock. The rhythm continues, now comprised of gentle, insistent tapping sounds that have the steady rhythm and assuredness of a warm rain on skin.

As the camera dips under, the gurgling rushes of the river return.

The high-pitched bird songs return as the tapping fades.

A voice cries out.

A deep, startled exhale as a branch snaps, followed by a slow splash.

The airy rhythm returns, a ticking made of breath, tongue, and teeth, quickly switching to the drumming of flesh against a surface. The drumming grows louder, softens, and then abruptly halts.

A soft voice, the slight kiss of breeze brushing past is audible around them:

Thank you

All sound ceases.

The off-camera voice speaks:

Scum on the top of the river, skin on the top of milk, skin on the top of the river, scum on the top of milk. The River Cole is constantly threatening to flood like I am, like we are.

[a deep breath]

The limb, the Cole’s River limbs flailing upstream towards her mouth and her teeth. When you drink a glass of water you also drink its ghosts. When you piss in the mouth of the river, your wastes embrace her pasts. Do keep body movements minimal. Do move and gesture slowly and naturally. Do maintain eye contact by looking straight in the camera. Bodies and the law are diametrically opposed. And the power of the police and/or men comes from somewhere else from flesh or bone or viscera, rather from unwoundedness, calcifications, non-porous materials. The virus sits on these materials but does not penetrate them. Rather, she waits. Scum on the top of the river, skin on the top of milk, as the river flows it picks up sediment from the riverbed, eroding banks and debris in the water. The river mouth is where much of this gravel, sand, silt, and clay is deposited.

The haunting song interjects:

Turns people into cla-ay.

Immediately the singer transitions back to speech:

The police hate water because it does not obey the law and because they cannot swallow or incorporate her. Kill the cop in your head to lose your tongue and exit language, swim in the blue lagoon now dyed black, let algae stick to you and stop holding hands. Cling to the viscera in your head, kill the cop in your high-wage, high-skill, high-productivity economy.

The Prime Minister says he does not care if you die, but that is because he does not understand that the dead are still a threat to him and to the law. When you drink a glass of water you also drink its ghosts. When you piss in the mouth of a river you also come in her pasts.

The haunting song interjects, gaining speed: Rivers turn to mud, eyes melt into blood

The water rushes in the background, a gentle but ceaseless torrent of sound.

The mouth of my mouth and the spit of the river, I am meters away from you and in the river holding my breath and still sucking up your sediments discharging foam and teeth. Foam on the water, sign of life and death.

The virus and the river water slither down policemen’s teeth or cheek, resides there. The mouth becomes the source, becomes the rapid and the edge. You find the bones of children sometimes, soft hands on necks or weeds tangled between toes and mud and stinking flesh. Amniotic fluid often spills before it breaks, and sometimes fishes also die, she said, as eggs come tumbling onto scales and gills and mammalian hair on legs. Eggs are always a disaster or a triumph, like the river and your viscera, or the virus and the sea. Do keep minimal straight body naturally across the path to keep the other and the virus safely out and maintain body and maintain eye appeal to the warm contact camera contact nature keep slowly looking straight into the body.

The haunting singing emerges from the background, so soft as to be nearly indecipherable. It hovers in the back of the mind of the video. It sings:

And so in the sky shines the electric eye

Supernatural king takes earth under his wi-ing

The speaking voice off camera continues, edges of phrases and sentences blurring and piling upon each other in a near breathless torrent of words:

There caught in the elbows of fallen trees are curving mounds of white foam. Police are called about a water in the body and a body in the water or the river found dead across the edge or bursting skin cells multiplicities and masks and balls at the end of your arms at the end of the ball at the end of nothing. Rehabilitation of the riverbanks are getting better, but what if we never get better or go freckles forward, but what if we never get better or go forward but circle around rather in and out.

The volume of the song in the background swells. It progresses still at a slow, haunting pace, but feels bolder, more confident, less content to linger:

Heaven’s gold chorus sings

Hell’s flap their wi-ings

Evil souls fall to hell

And they’re trapped in burning cell

Da na now, da da na now. Doo duh da na now, da na na now. Da na now, da na na. Duh nuh nuh, Buh buh na na,

The sound of rushing water in the background abruptly ceases, leaving only the singing voice to continue with its interpretations of Black Sabbath’s guitar.

A beat picks up, both in time to the rhythm of the syllables being sung, recalcitrantly deviating at others.

Doo doo do-do, doo doo do-o

Buh buh buh, buh buh-a

Buh buh na na

Duh Duh duh now

Buh buh buh, buh buh-a

The beat increases in speed, becoming a frantic heartbeat for a few seconds before disappearing entirely.

The song continues softly:

Buh-a. Duh na. Duh na.

Barely audibly, the voice concludes, still on pitch and beat with its song, leaving us with a gentle, hovering syllable:

Mmm

I was recently told about this program by a friend as they suggested it might be relevant to my practice. As it sounded super interesting to me, I was worried that it might just be a radio recording without subtitles. But then I was happy to find that there was a subtitled video for people like me – D/deaf people and hard of hearing. My relationship to radio has been pretty much non-existent, the only time I would hear it is when the car didn’t have any interesting music to play, my mom would always turn it on for background sound.

In this 28 min-long video, the Deaf poet Raymond Antrobus talks about his experience with radio, subtitles on TV, and translating sound within the hearing world. Words on the video are constantly flickering, as though we are watching on old static TV. Simultaneously, words are spoken in a flat monotone with interviews from artists and writers in their interpreter’s voices.

Throughout the video, commentaries are shown from Deaf artist (Christine Sun Kim) and Deaf poet (Meg Day), filmmaker (Lindsey Dryden), and caption maker (Calum Davidson), discussing what closed captions mean to them. I found this video really great as it really resonated with my experience and brought back my memories of constantly trying to find something on TV that provided subtitles. In particular, there was a reference by Lindsey Dryden to the film Dawn of the Deaf by Rob Savage. The film makes clever use of subtitles by partially showing them during a scene of a couple fighting using BSL, intentionally not showing the audience the full context of the argument. The mentioned short film can be found on Rob Savage’s website (the video is subtitled).

BBC Radio 4’s “Invention in Sound” can be found on the BBC website- the transcript is also available for download as well.

-Subtitles can easily change the context of video being shown.

-Subtitles can either tell us so much and so little.

-Size and placement of subtitles can be important as they can either hide or reveal what is happening on screen.

-How can the subtitles translate sound?

In my research posts, I would like to include questions, bullet-pointed lines of thinking, comments, and references. Please let me know if you have any questions!

During this week I am hoping to explore more into the unique language of subtitles and begin searching through film archives for more references. I wanted to ask everyone – what does sound mean to you? What is your experience with subtitles?

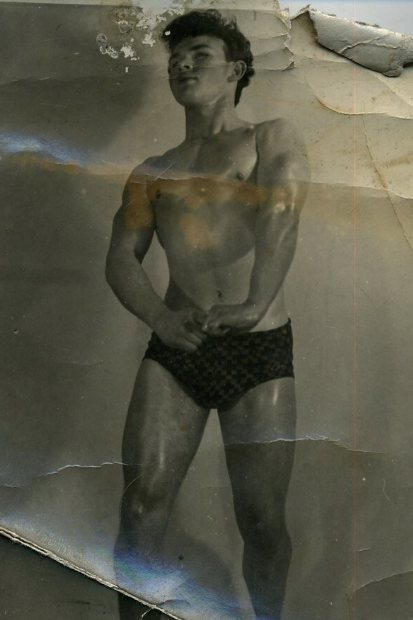

Ray Jones, born 1950 on a council estate in Derby, a saxophonist, a freemason, an enthusiast of obscure experimental films and a collector of strange art prints, a Body Builder, a statue frozen in time, a mystery.

My deceased Dad, who died of a heart attack when I was almost 3 years old, is where I think I can mark my first awareness of hyperable bodies. They’d lift weights together my Mum told me, they’d run up and down the flights of stairs in their highrise apartment building my Mum told me. I still have a couple of his gym tops she gave me.