2019

Image Description: Watershed

Linda Stupart Watershed 2020, video, 11:06

Image Description by Aubree Penney

Image Description

Clad in black galoshes, a person wades into a small, murky river, past an abandoned shopping cart that lies in the water nearby. The person’s outfit consists of pink, yellow, baby blue, and lavender tie-dyed pieces and bits of pink pastel plastic. The arraignment drips behind them, dragging the ground, covering their head like a hood in a cheerily chaotic hodgepodge of pastel bits and pieces. Bright yellow tie-dyed gloves are on their hands. Lush greenery surrounds one side of the river, with tangles of roots emerging near the waterline.

They walk away from the camera towards a brick bridge with two arches, circles of water rippling out from their feet with each step.

Splashes of water accompany each of the figure’s steps, as the chitterings of birds mix with the rush of passing traffic and the light whisper of wind.

A warm, welcoming voice off-screen layers over the background noises of the river:

Ok, so, everyone close your eyes. Ok. So, now that your eyes are closed I want you to really think about the spit that’s in your mouth. So like everyone has spit in their mouth. Just be really aware of that spit in your mouth.

Ok, so you’ve got the spit, it’s there, it’s in your mouth. Now what I want you to do is imagine that there’s a cup in front of you. You’ve got a cup, it’s empty, maybe it has some water in it. It’s in front of you. Now, I want you to think and imagine spitting that spit out into the cup in front of you. Ok. Cool. Now that you’ve done that, I want you to pick that cup up and drink that spit back into your mouth again.

The camera dips into the water, revealing a tumult of sticks and dirt, decomposing leaves, and a white strand.

The camera shifts angles, revealing the figure emerging from beneath the brick bridge. A stone wall with trails of ivy meets the bridge at its top, containing the river, with a wealth of greenery emerging from the damp land at the river’s far edge, piles of stones and debris on the bank nearest the camera. The river narrows to only a few meters’ wide.

On screen text beneath the figure reads: The long arm of the law was in full evidence when police were called to reports of a human limb floating in a Birmingham river.

Splashes accompany the slow, steady movement of the figure in the water as the birds continue to sing.

On screen text beneath the figure reads: And the officers went further out on a limb after they struggled to get out of the river – providing amusement to those watching the operation to retrieve the wayward body part.

The voice off-screen clears its throat, which echoes slightly, before beginning to sing Black Sabbath’s “Electric Funeral.” The pace is slow, lingering, sung in a rich middle range and lending a haunting air. The song clings to your skin, subtle but insistent. The sounds of the riverbank continue in the background, the twittering of birds lightly piercing the darkness of the sung melody.

The voice sings:

Ba, ba da nuh nuh, duh nuh nuh, duh nuh nuh, ba ba

The gurgling of the river replaces the sound of birds as the camera dips into the water.

The camera plunges and twists beneath the water, revealing dirt and detritus in the grayish water and offering momentary glimpses of the figure’s pastel robes, stirring bubbles beneath the water and a blue sky above streaked with white clouds.

Our view shifts back to the figure, slowly proceeding along the river. A black and white image of an arm layers over the left side of the image. The arm is wrapped in something at the elbow, the skin looking mottled and patchy. The hand is outlined in yellow, raising it against the screen. Behind the picture of the hand is a vertical video hovering over a container of orange goop with bits pressed into it. The video of the orange goop disappears. In the center, beneath the black and white hand appears the image of a blue-gloved hand holding a white, stuffed glove with blood on its fingertips in front of a river with rocky banks and lots of trees around it.

The figure approaches a small waterfall.

The camera shifts to the top of the waterfall. The black-and-white hand image disappears, shortly followed by the disappearance of the image with the stuffed glove.

The figure clambers over the falls and stands at the top, revealing in their hand a Y-shaped wooden diving rod, with orange string and a small camera at the top. A tattoo peeks out just beneath their right elbow.

The voice continues to sing:

Reflex in the sky-y warn you you’re gonna di-ie

Storm coming, you better hi-ide from the atomic ti-ide

Flashes in the sky-y turns houses into sti-ies

Turns people into cla-ay, radiation mines deca-ayyy

The voice emulates a guitar interlude, the sound becoming increasingly sharper and more insistent:

Dee da na now, de duh na now, do do duh na now, dee dee nuh nee, duh duh da now, dee dee nuh nee,

Bow bow buh na now, duh nuh nee

Robot minds of robot sla-aves

Lead them to atomic ra-age

Plastic flowers, melting sun

Fading moon falls apart

Dying world of radiation

Victims of mad frustration

Burning global oxy’n fire

Like electric funeral pyre

The figure continues their journey, the waterfall now behind them. They reach down and grab a long, thin branch, untangling it from their clothes. They toss it behind them, the branch eliciting a small spray as it smacks the water.

A light splash joins the sound of the figure wading as they throw the stick in the water.

Duh da na now, de nuh na nee, ba ba da nuh, dee nuh na nee

Ba bow duh na now, nuh nuh na

The figure progresses between two piles of sticks in the river, speckled with castoff bottles and other pieces of rubbish.

The voice transitions to the rhythmic, airy flicking sound of a tongue flicking the top teeth, steady as the second hand on a clock. The rhythm continues, now comprised of gentle, insistent tapping sounds that have the steady rhythm and assuredness of a warm rain on skin.

The camera dips beneath the water, revealing murkiness and the pinks of the figure’s robes once more as well as the verdant edges of the bank.

As the camera dips under, the gurgling rushes of the river return.

An inset box, framed now by murkiness, reveals the figure navigating under and around a low canopy of branches that are over the river. A fingertip briefly slips in front of the camera lens.

The high-pitched bird songs return as the tapping fades.

The background image shifts to the figure wading towards the camera. In the foregrounded image, the figure trips on a branch and slowly falls into the water. They slowly sit up and begin to remove their mask.

A deep, startled exhale as a branch snaps, followed by a slow splash.

The airy rhythm returns, a ticking made of breath, tongue, and teeth, quickly switching to the drumming of flesh against a surface. The drumming grows louder, softens, and then abruptly halts.

The image cuts to a skinned knee with blood dripping down, leaving rust colored trails behind on the pink skin, the damp pink, yellow, and light blue fabric hanging about the hurt leg. The camera twists, revealing a tattoo beneath the skinned knee, now black lines merging with light pink streaks of blood as the blood drips past the tattoo and down into the rainboot.

A soft voice, the slight kiss of breeze brushing past is audible around them:

Thank you

All sound ceases.

The camera pauses on the figure’s head, covered in a gray and pink floral mask with huge half-sphere eye pieces of clear plastic. Bits of lavender and laminated fronds are revealed to be part of the ensemble. The figure’s right hand wears a yellow tie-dyed glove and holds the diving rod aloft. Bits of orange yellow, white, and pink string adorn it, mixing with wires and buttons for technology and a laminated paper that reads “Deriving from the Latin word vulnus [wound], vulnerability expresses the capacity to be wounded and suffer. As bodily, social, and affective beings, we all have the capacity to be vulnerable to one another and to conditions of inequality, discrimination, exploitation, or violence, as well to the natural environment. The next sentence is crossed out.

The sloshes of the water and bird songs return.

The figure proceeds onward down the dirt bank beneath an organically formed archway of trees and bushes. Tiny, lacy white flowers dot the ground to either side of the dirt path.

The off-camera voice speaks:

Scum on the top of the river, skin on the top of milk, skin on the top of the river, scum on the top of milk. The River Cole is constantly threatening to flood like I am, like we are.

[a deep breath]

Superimposed on the screen is a collaged tangle of daisies, leaves, yellow and green slivers, a cacophony of soft angles and cheery natural hues. Behind the collage, the figure steps back into the river and proceeds on their journey, greenery visible on both sides of the water.

The limb, the Cole’s River limbs flailing upstream towards her mouth and her teeth. When you drink a glass of water you also drink its ghosts. When you piss in the mouth of the river, your wastes embrace her pasts.

The image of the blue-gloved hand holding the stuffed white-gloved hand in front of the river is superimposed over the collage.

Do keep body movements minimal. Do move and gesture slowly and naturally.

The superimposed images disappear, giving a clear view of the figure wading in the river, their divining rod in their right hand.

Do maintain eye contact by looking straight in the camera.

The collage of leaves and daisies and ephemera and the image of the blue-gloved hand holding the stuffed white glove in front of the river are superimposed over the figure’s journey again.

Bodies and the law are diametrically opposed. And the power of the police and/or men comes from somewhere else from flesh or bone or viscera, rather from unwoundedness, calcifications, non-porous materials.

The collage disappears. The superimposed image of the stuffed white glove shifts to a video showing reflection on the water’s surface and then scum at the bottom of the river, a glimpse of the divining rod, then more brown debris and dirt beneath the water.

The virus sits on these materials but does not penetrate them. Rather, she waits. Scum on the top of the river, skin on the top of milk, as the river flows, it picks up sediment from the riverbed, eroding banks and debris in the water. The river mouth is where much of this gravel, sand, silt, and clay is deposited.

The superimposed video disappears, leaving only the figure in the river.

The haunting song interjects:

Turns people into cla-ay.

On-screen text at the top of the page, in white text atop an image of river water: the police hate water because it does not obey the law

Immediately the singer transitions back to speech:

The police hate water because it does not obey the law and because they cannot swallow or incorporate her.

The on-screen text disappears. A black and white image of a right hand, marked with red bits and globs of ooze, a bit of red flakiness at the center, appears in the bottom right corner. The hand is surrounded by a thick yellow line.

Kill the cop in your head to lose your tongue and exit language, swim in the blue lagoon now dyed black, let algae stick to you and stop holding hands.

The image of the oozing hand disappears. The figure has almost reached the limits of visibility for the camera and glances back quickly, then proceeds onward.

Cling to the viscera in your head, kill the cop in your high-wage, high-skill, high-productivity economy.

The Prime Minister says he does not care if you die, but that is because he does not understand that the dead are still a threat to him and to the law. When you drink a glass of water you also drink its ghosts. When you piss in the mouth of a river you also come in her pasts.

A path of spaced stones spans from one bank to the other, forming a walking path. A huge, decaying log sits to the right. Water flows between each stone, forming tiny waterfalls as the water changes levels by a few feet. The camera gets closer and closer, revealing moss on the stones of the path and the foam at the bottom of the miniature waterfalls, and begins to cross the river.

The water rushes in the background, a gentle but ceaseless torrent of sound.

The haunting song interjects, gaining speed and urgency:

Rivers turn to mud, eyes melt into blood

A wobbling clip of tan eggshells on the dark riverbed is superimposed atop the pathway of stone and waterfalls.

The mouth of my mouth and the spit of the river.

The camera swivels at the center of the river, revealing the figure slowly proceeding towards us, flanked on either side by tall trees and lush tangles of small white flowers. Birds dart across the river, making ripples as they touch down, and a huge limb lies in the midst of the water.

I am meters away from you and in the river holding my breath and still sucking up your sediments discharging foam and teeth.

The video of the bloody knee, surrounded by pastel swaths of the figure’s attire, is superimposed atop the river scene, framing the knee with greenery and rippling waters.

Foam on the water, sign of life and death.

The virus and the river water slither down policemen’s teeth or cheek, resides there. The mouth becomes the source, becomes the rapid and the edge.

The superimposed image disappears.

You find the bones of children sometimes, soft hands on necks or weeds tangled between toes and mud and stinking flesh. Amniotic fluid often spills before it breaks, and sometimes fishes also die, she said, as eggs come tumbling onto scales and gills and mammalian hair on legs.

A video of the figure kneeling in the water, holding their masked head with their left hand and dipping their divining rod into the river with their right. A white stuffed glove is visible next to the rod. The figure slowly moves the rod in the river, its strands of fabric and ephemera floating, shifting with the motion of the rod and the current.

Eggs are always a disaster or a triumph, like the river and your viscera, or the virus and the sea.

The superimposed image disappears. The figure uses the rod for stability as they continue towards us, navigating around the branch in the midst of water.

Do keep minimal straight body naturally across the path to keep the other and the virus safely out and maintain body and maintain eye appeal to the warm contact camera contact nature keep slowly looking straight into the body.

The haunting singing emerges from the background, so soft as to be nearly indecipherable. It hovers in the back of the mind of the video. It sings:

And so in the sky shines the electric eye

Supernatural king takes earth under his wi-ing

The speaking voice off camera continues, edges of phrases and sentences blurring and piling upon each other in a near breathless torrent of words:

There caught in the elbows of fallen trees are curving mounds of white foam. Police are called about a water in the body and a body in the water or the river found dead across the edge or bursting skin cells multiplicities and masks and balls at the end of your arms at the end of the ball at the end of nothing. Rehabilitation of the riverbanks are getting better, but what if we never get better or go freckles forward, but what if we never get better or go forward but circle around rather in and out.

The water grows deeper as the figure nears the camera. The figure’s steps become more tenuous, deliberate as the water reaches their thighs. They sink down with the divining rod, the water level up to their chest.

The volume of the song in the background swells. It progresses still at a slow, haunting pace, but feels bolder, more confident, less content to linger:

Heaven’s gold chorus sings

Hell’s flap their wi-ings

Evil souls fall to hell

And they’re trapped in burning cell

Da na now, da da na now. Doo duh da na now, da na na now. Da na now, da na na. Duh nuh nuh, Buh buh na na,

The figure leans back, immersing themselves entirely. The screen goes black.

The sound of rushing water in the background abruptly ceases, leaving only the singing voice to continue with its interpretations of Black Sabbath’s guitar.

A white text box appears on the black screen. It reads:

PART 1

Shot on location in the River Cole (Sparkhill – Hall Green)

Filming by Tom Dillon

Song by Black Sabbath

A beat picks up, both in time to the rhythm of the syllables being sung, recalcitrantly deviating at others.

Doo doo do-do, doo doo do-o

Buh buh buh, buh buh-a

Buh buh na na

Duh Duh duh now

Buh buh buh, buh buh-a

The white textbox disappears, leaving only a black screen.

The beat increases in speed, becoming a frantic heartbeat for a few seconds before disappearing entirely.

The song continues softly:

Buh-a. Duh na. Duh na.

Barely audibly, the voice concludes, still on pitch and beat with its song, leaving us with a gentle, hovering syllable:

Mmm

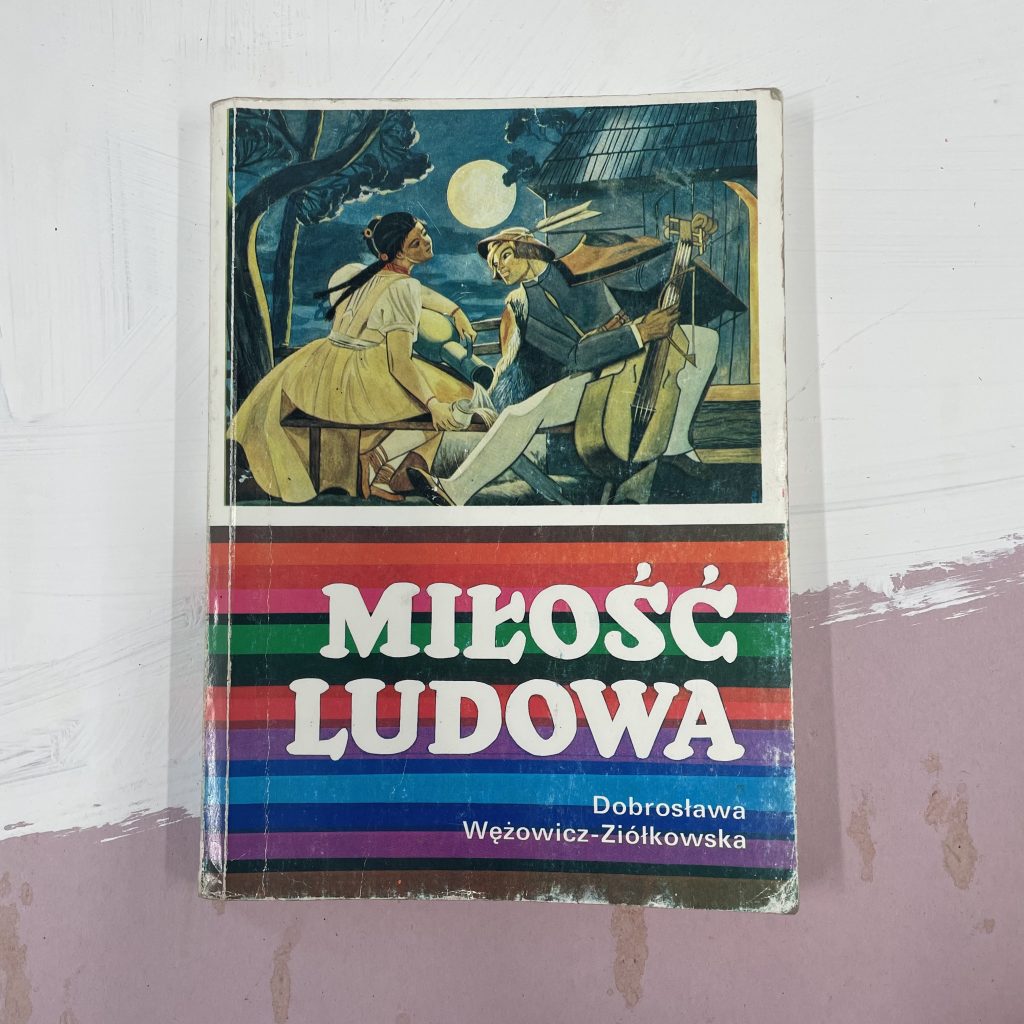

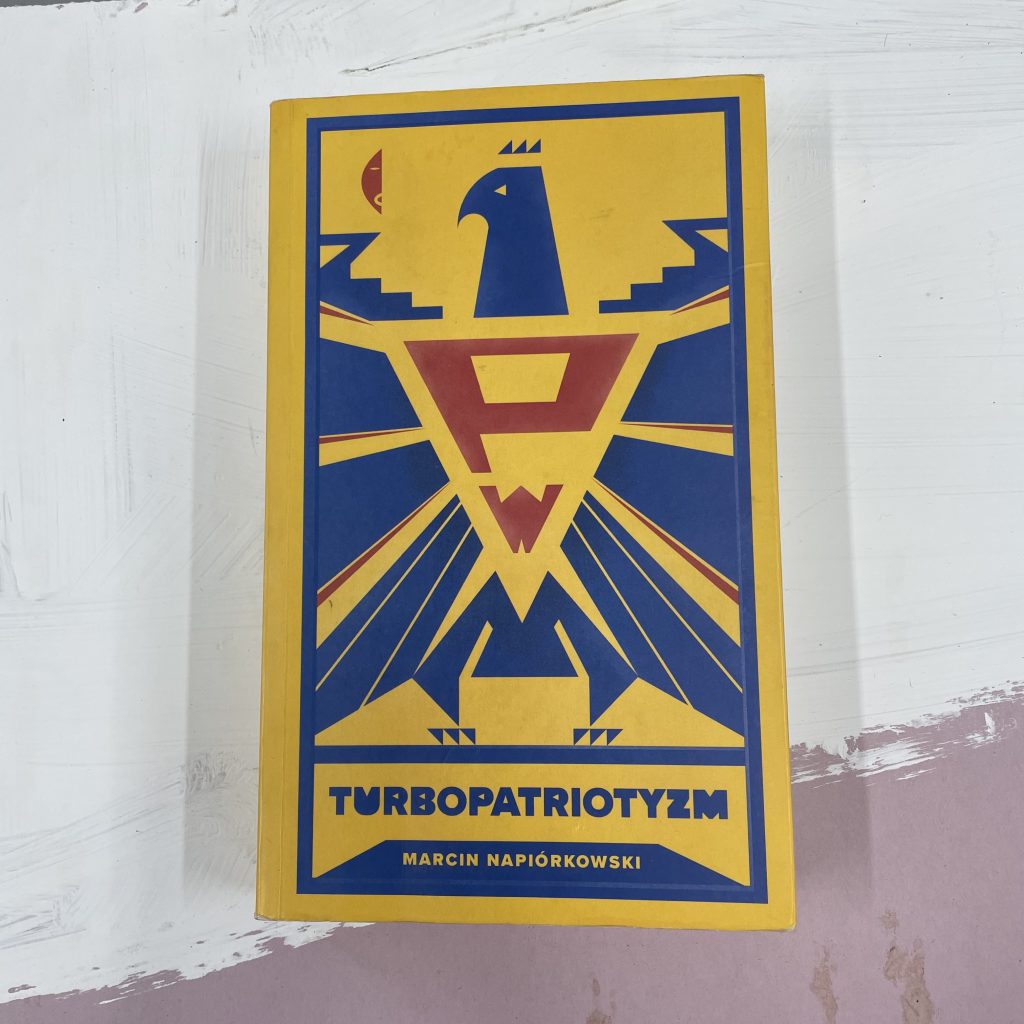

Here some of the books I am reading as part of my script research.

Images description:

Nine images presenting the books. First image: A pile of eight books on white / pink table, white wall at the background. Second: Book on the table. Title: Milosc Ludowa (Folk Love) by Dobroslawa Wezowicz – Ziolkowska. Cover shows illustration with a women and man in Eastern European folk costume , with moon behind them, test of cover is multi colour strips. Third: Book on a table. Yellow cover book, with blue eagle and a red symbol inside, book title ‘Turbopatriotyzm’ (Turbo Patriotism) by Marcin Napiorkowski. Fourth image: Book on a table. Old english looking, black, beige colour. Book title: ‘Old English Customs, Extant at the Present Time, an Account of Local Observances’ by Peter Hampson Ditchfield. Image five: book on a table, grey cover with yellow writing CRAFT, Edited by Tanya Harrod. Image six: Book on a table, light beige colour, black writing with book title ‘ Traditions, Superstitions and Folk – Lore by Charles Hardwick. Image on the cover show an evil looking creature beating bunch of medieval looking white people with a whip. White bigger women at the background smiling and undefined small creatures in front of her. Image seven: Book on a table, communist style monument on blue sky background. Title in red and white, ‘Turbo Folk Music and cultural representations of national identity in former Yugoslavia. Eight image: Book on a table, blue red cover, title in Polish ‘ Ludowa Historia Polski’, Folk History of Poland’ by Adam Leszczynski. Image nine: book on a table, orange cover with image of English aristocratic looking white man between two lions, male and female, who is licking his face. He is embracing them both and there are little tigers running around. British Folk Art is the book title.

Although most recently I’ve been focusing on creating the residency risograph prints, this post returns to the idea of context as a fundamental factor in untangling lipreading, typographic and AI errors. Lipreading is often like completing a giant freeform crossword puzzle; filling in one set of clues reduces the parameters for the next set, and the next. Context enables you to instantly discard broader variables and zoom in on the most likely possibilities. Working with BSL/SSE interpreters does the same thing; while “vignette” and “finesse” will create almost identical lip patterns, the BSL interpretations use completely different hand shapes and movements.

Lipreading is physically impossible with masks, but there’s also loss of facial expression giving tone & context. But there are still contextual clues; where are you, what’s happening around you?

The same issues seem to be occurring with AI transcription; I examine the context in which errors occur to try to work out what the most likely interpretation is. This is a real challenge as you’ve a tiny amount of time to expend before the conversation moves on – with possibly another set of mangled meaning to decipher. The last work I’ve made looks at this mental juggling by using the risograph duotone process to “correct” mangled AI using proofreaders marks, to represent the two simultaneous thought processes. That work will be in the residency exhibition, but here’s a few puzzles for you to be going on with.

“The moose doesn’t strike any emotion.”

“The perfect cinnamon.”

“I know there is a framework for achieving Oswald by doing do command Libra.”

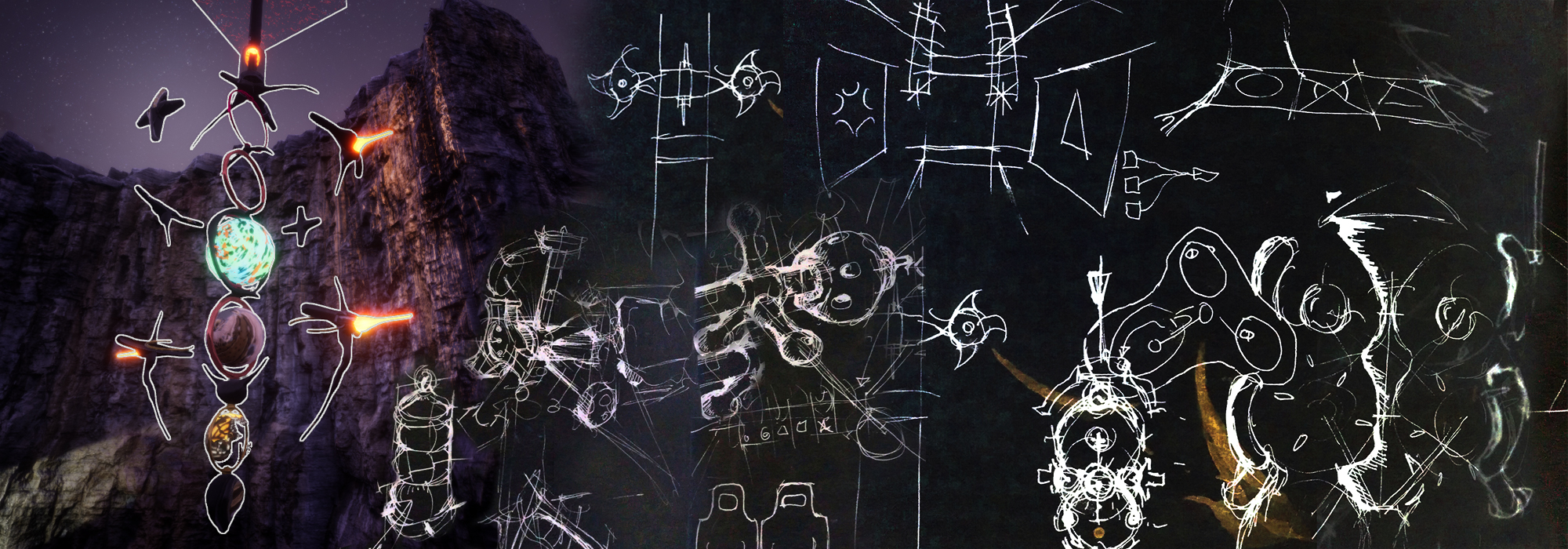

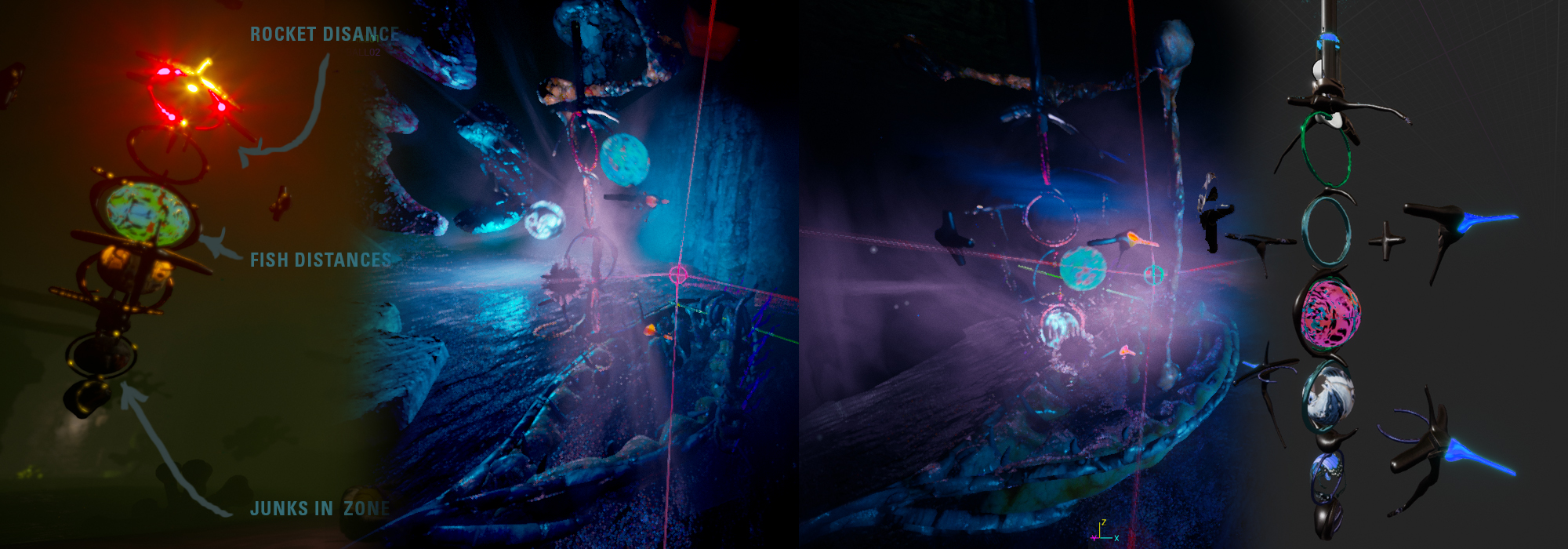

I think a good landscape should be enticing and thought-provoking. The power of landscape design is immense and should never be underestimated. As I mentioned before for this reincarnation of Tuner I plan on bringing it back underground to grow the sense enclose, need for air and to assist in the game plays interactions of fish collecting practices.

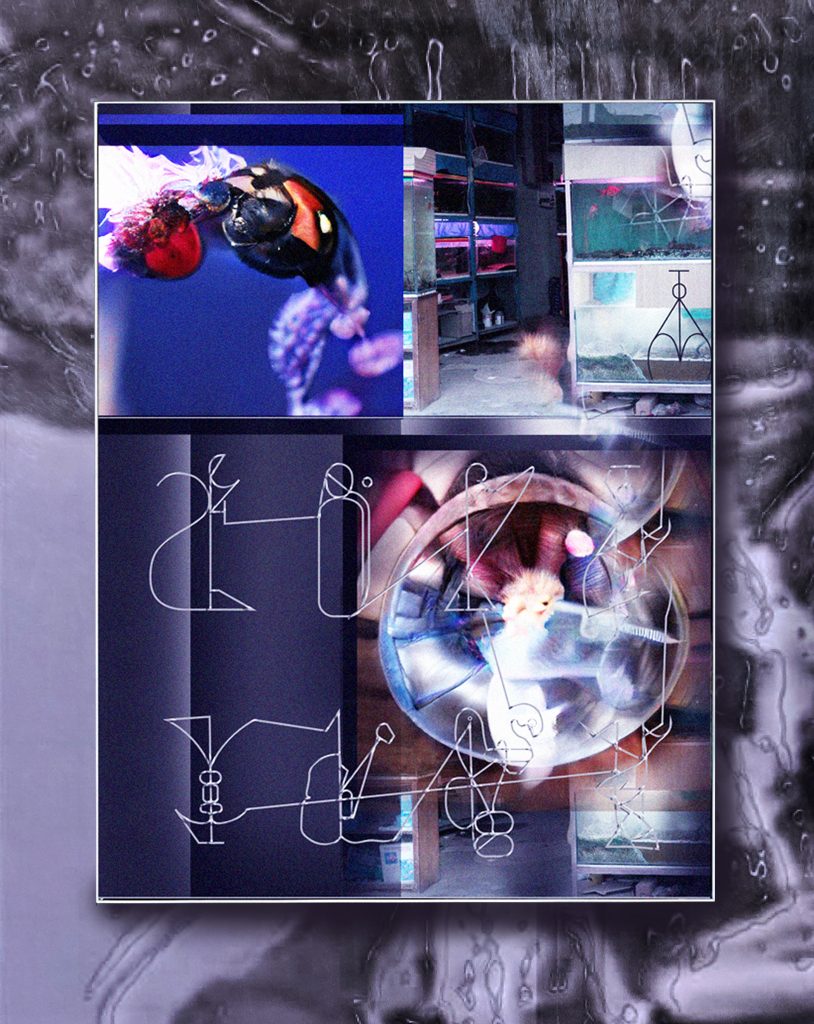

SCANNERS The Scanner is like a radar mechanism, when found and attached to the boats roof hook, all 3 of it orbs rotate about their orbits, at each turn displacing a line to their nearest corresponding subject, ie Fish, Junk and Rockets. All these three orbs speeds can be controlled individually sonically creating an ever phasing sequence. Initially this control was access via the Midi protocol each orb having their own physic knob here on earth. But now the foam of interacting will need to be re-designed into the GUI interface.

The Scanner is like a radar mechanism, when found and attached to the boats roof hook, all 3 of it orbs rotate about their orbits, at each turn displacing a line to their nearest corresponding subject, ie Fish, Junk and Rockets. All these three orbs speeds can be controlled individually sonically creating an ever phasing sequence. Initially this control was access via the Midi protocol each orb having their own physic knob here on earth. But now the foam of interacting will need to be re-designed into the GUI interface.

The scanner is also a lantern for dark zones epically when the internal torchlight fades due to the boats’ strength depletion . I will supply the new scanner in operation (video), here below are some (blurred) old in game shots.

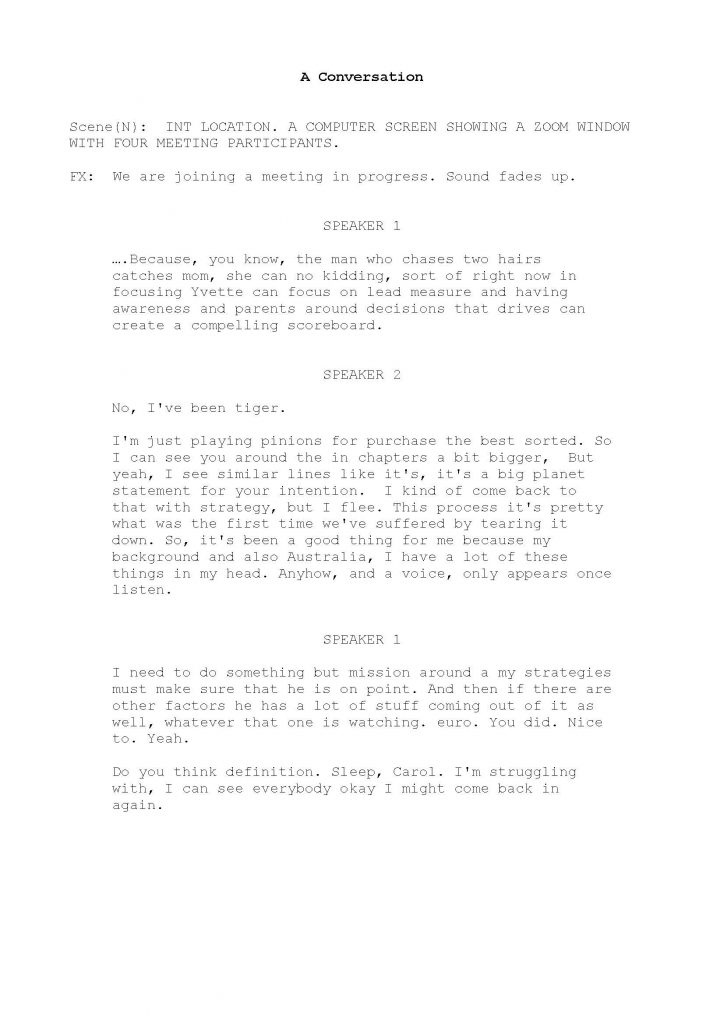

This week I’ve been focusing on practicalities for making risograph prints. As my region (England) is in lockdown, this involves a lot of forward planning, material purchase and prep that’s not very interesting to read about. So I’ve also been experimenting with AI transcripts to create a little script from some of the most egregious examples of distortion (looking at you, Microsoft Teams).

This has been added as a document and images.

The aim is to give the reader a feel of what it’s like trying to make sense of a situation which isn’t accessible, and the impossibility of acting on information which doesn’t make sense. During the current pandemic, misunderstanding is not merely an amusing anecdote (a la Auberon Waugh’s tale of mishearing “press freedom” and delivering a lecture on “breast feeding”), it’s dangerous. Currently, the UK offers no BSL interpretation for government briefings. While the BBC provides interpreters for government announcements, not everyone has access to the BBC, and clips shown on social media won’t be inherently accessible. And scientific briefings are not shown with BSL interpretation. It’s the government’s responsibility, not the BBC’s. Too many organisations push the responsibility for accessing information onto individuals rather than thinking about how they can make it straightforward.

So, anyway, I’ve been tiger, because you know, the man who chases two hairs catches mom.

I was taught lipreading before I began using BSL (British Sign Language) and use the two communication methods contiguously. The term “lipreading” is somewhat misleading, as it’s not just lip patterns that contribute to understanding – you pick up information from the rest of the face, from body language, and from the contextual environment (context is something I’ll be picking up on again). My biggest obstacle is dark sunglasses that block the information you see around people’s eyes; if lip patterns provide information on words, the eye area often gives the equivalent of tone of voice, and lipreading people wearing sunglasses translates as a monotone to me.

During 2020, the ratio has been flipped, with masks preventing lipreading, but often leaving the eyes and surrounding areas clear; I’ve started to notice that I still pick up information, so can (sometimes) recognise tone, even if there’s no way to pick up words. I’ve also noticed hearing people struggling with understanding (with masks muffling voices), and am wondering if this will impact on people’s thinking about hearing loss in the longer term. Will their own difficulties lead to more understanding? Will they turn to D/deaf people as communication experts they can learn from?

I’ve been playing with images from the 1986 edition of “Lipreading – A Guide for Beginners”, masking the lip patterns illustrated. I’m planning a duotone risograph print, perhaps using several of these images – due to local lockdown I can only prep my files at present, so anything shown at this stage is an approximation.

In 2017, the original creator of Minecraft Markus ‘Notch’ Persson made a series of controversial comments on social media, such as referring to feminism as a “social disease” and claiming that most feminists are “overtly sexist against men.” In March 2019, he made a number of transphobic comments that eventually triggered backlashes including Hatsune Miku declaring herself creator of Minecraft.

Hatsune Miku is a Vocaloid software voicebank developed by Crypton Future Media (Japan) in 2004. The face of the Vocaloid is a 16-year-old girl with long, turquoise twintails. Soon after Notch published his tweets in March, queer Minecraft players decided to have the virtual superstar Miku as Minecraft’s creator.

Subsequently, Minecraft update silently removed references to Persson from the game’s menu, though his name is still in the credits. Persson was not invited to be part of the Minecraft tenth anniversary event later that year, with Microsoft saying that his views “do not reflect those of Microsoft or Mojang”

For this residency, I want to create a series of symbols from the Dutil-Dumas message as an intervention in a virtual art space. The work will reference a previous work Cosmic Call. (An audio description of the visuals in the trailer is available)

Cosmic Call is a work commissioned by Wellcome Collection in 2018

The main video weaves together facts and fiction to create an alternative understanding of epidemics. Cosmic Call resists the dominant narrative of a disease outbreak – a formulaic plot of a detective story about disease emergence and eventually the triumph of western medical science – and suggests multiple belief systems in which science is only one of many ways to understand communicable diseases. It points to the danger of reducing all knowledge to scientific terms while addressing issues that are pertinent to Hong Kong, which is characterised by its high population density and mobility – conditions that make Hong Kong extremely vulnerable to disease outbreaks.

In the video, an interstellar message (the Dutil-Dumas message) was sent by extra-terrestrial life forms that warned human beings of epidemics caused by passing comets. Information about the Dutil-Dumas message can be found on the RESEARCH section of the website.

Working with collage, internet scavenged images and constructed symbolism these lightboxes show a myriad of forms present within the natural world. Bodies of animals, fauna and scientific photographs are entangled together to represent the different ways in which humans percieve, understand and order lifeforms.

This short interlude in between parts 2 & 3 of the ‘Eviction in Shenzhen’ series, features ‘feng shui fish’ which are said to increase the wealth, luck, health and prosperity of its owners.

The fish include Koi Carp, Arowana’s, Blood Red Parrot Cichlid, Flowerhorn Cichlid, Oscar fish, Iridescent Sharks and Terrapins which are admired for their longevity and wealth attracting characteristics. This interlude interrupts

the chapter to speak of the values of which the Chinese people have including their desires, wishes and

dreams.

“In Chinese culture, the symbol of fish has two attributed qualities. The first one is the aspect of abundance

(because of the ability of fish to quickly reproduce in large quantities). The second one is the fact that the Chinese word for fish (yu) is pronounced the same way as abundance.” – Tchi. R (2019) Feng Shui Tips for Your Aquarium, online article www.thespruce.com/feng-shui-fish-for-wealth-1275337

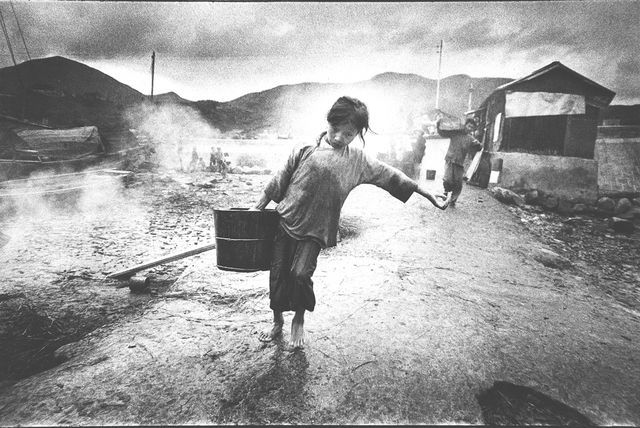

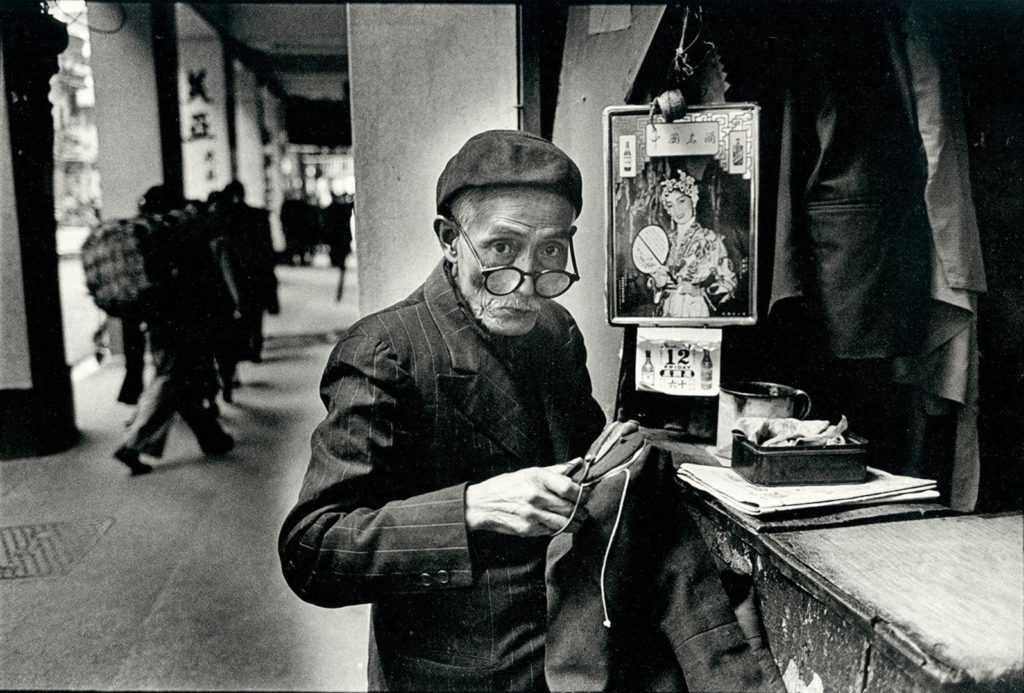

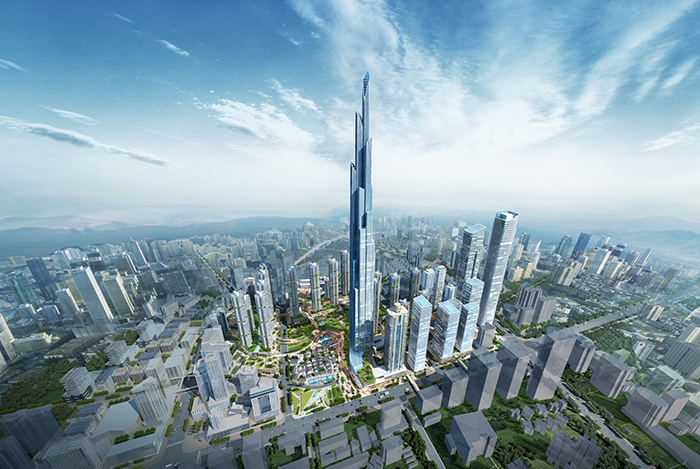

Eviction in Shenzhen (2019-Ongoing) is a long-term ethnographic series of experimental documentary films which follows the planned demolition of Cheung’s fathers ancestral village of Hubei in Shenzhen, China, as the government initiates a major redevelopment plan to take its place. The proposed project includes an impressive 830m tall skyscraper which is set to become the tallest building in the world. This will be accompanied with a modern shopping centre, restaurants, plus a small portion of Hubei Old Village preserved as a living museum and film location for hire. The new redevelopment will become one of China’s most prized architectural accomplishments, a visual spectacle, which pays homage to the economic miracle that is Shenzhen as the city which led China to its new position as a global economical and technological power.

The film marks the eviction of the current tenants of the village who as low-income workers, are having to leave behind the cafes, food vendors, small businesses, residential homes and communities which they cultivated over a period of 10 – 20 years. Eviction in Shenzhen filmed over the course of this redevelopment period, will document these changes by recording the sociological make-up and ancient architecture of the village as it gradually disappears.

The film is currently in development and will proceed in chapters as the project develops. ‘Eviction in Shenzhen: Part 1’ (2019 – Version 1) captures the residents of the area during a visit to the area in May 2018. The next chapter filmed during February 2019 features the area taken during Chinese New Year, with a near 90% of residents now fully evicted.

Directed, produced and edited: Seecum Cheung

Sound design: Natalia Domínguez Rangel

Story of cities #25: Shannon – a tiny Irish town inspires China’s economic boom

Created in 1959 to lure foreign investors with tax breaks, the Shannon Free Zone proved revolutionary across the world. But in today’s world of looser trade and tax havens, Ireland’s innovators face an uphill battle to stay relevant

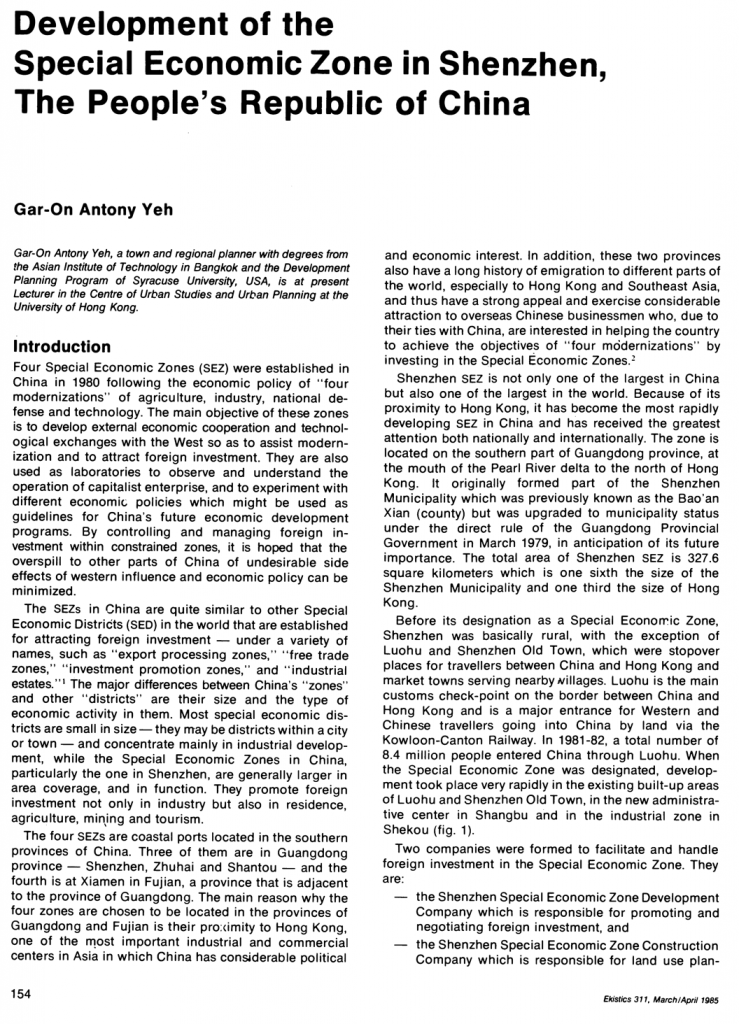

Yeh, G. (1985). Development of the Special Economic Zone in Shenzhen, The People’s Republic of China. Ekistics,52(311), 154-161. Retrieved October 23, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/43622838

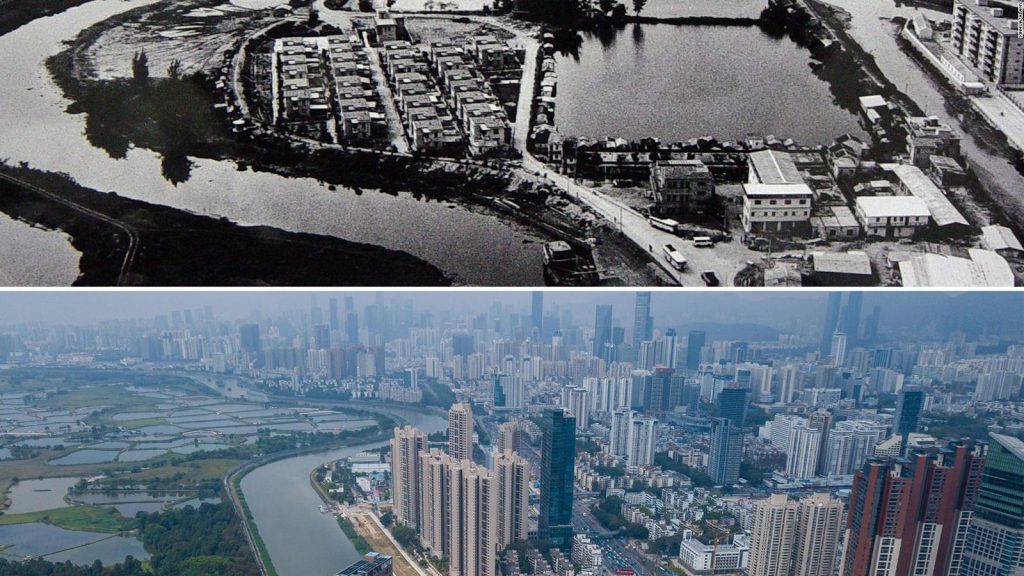

“No city in the world has ever grown as rapidly as Shenzhen, China’s southern gateway to the outside world. In 1978, when the Reform and Opening policy was introduced in China, Shenzhen was a small town of some thirty thousand people, surrounded by paddy fields. By 2010, it had a population of more than ten million people – more than New York, America’s largest city. No tall buildings were more than thirty years old. It glittered with modern stores, hotels, offices and restaurants.” – Foreword, Ezra Vogel

Focusing on Shenzhen as a representation of the general urban village phenomenon in China, this book considers the impact of China’s economic reform on urbanization and urban villages over the past three decades. Shenzhen’s urban villages are some of the first of their kind in China, unique in their diversity and organizational capacity, but most notably in their ability to protect village culture whilst coexisting with Shenzhen, one of the fastest urbanizing cities on earth. Providing a study of regional contrast of urban villages in China with newly collected fieldwork materials from Guangzhou, Beijing, and Xi’an, this book also considers recent developments within urban villages, including attempts at marketization of the so-called xiao chanquanfang (the quintessential urban village apartment units). It also addresses the corruption scandals that engulfed some urban villages in late 2013. Through cutting edge fieldwork, the author offers a cross-disciplinary study of the history, culture, socio-economic changes, and migration of the villages which arguably embody Chinese social mobility in an urban form. Da Wei David Wang (auth.)

“In Global Burden of Disease Study 2013, China alone accounted for 17% of the global mental illness burden and the burden of mental illness was expected to increase by 10% in China between 2013 and 2025 (Charlson et al. 2016).”p2

“Risk factors specific to each phase would negatively influence the mental health of immigrants, i.e. early age at first migration and ‘no clear motive for migration’ before migration (Takeuchi et al. 1998; Fenta et al. 2004), exposure to violence during migration (Bhugra, 2003) and poor language skills in the host country language after migration (Mirsky et al. 2008; Im et al. 2014)”. p2

“This study was part of a large-scale cross-sectional sur- vey (Zhong et al. 2015), which investigated mental health of factory migrant workers in Shenzhen, China, between August 2012 and January 2013. Shenzhen is a modern metropolis in southeastern China. As one of the major destinations for migrants from impoverished western and central inland regions of China, it has been China’s largest migrant city with 7.8 million rural-to-urban migrants in 2012 (Zhong et al. 2015).”

“In brief, we first purposively selected ten factories (three electronic, two machinery, two shoes, two cosmetic and one garment) to represent factories of Shenzhen. Second, a total of 41 production units (2–6 units/factory) were randomly selected from the 397 production units of the ten factories. Finally, all eligible subjects of these identified units were invited to participate in this survey.”

“The seven items were: (1) Migration work improves my personal economic conditions; (2) Migration work improves my family’s economic con- ditions; (3) Migration work improves my working abil- ities; (4) Migration work gives me a good opportunity to make many friends; (5) Migration work makes me realise personal economic independence and freedom; (6) Migration work enriches my social experiences; and (7) Migration work makes me realise personal life value.”

“Results of the univariate analysis (Table 1) show that significantly higher CMHPs prevalence rates were observed among migrant workers who were young, had a low level of educational attainment, had a marital status of ‘others’, reported poor living condition, had a low monthly income, were ill in the previous 2 weeks, migrated before adulthood, worked outside hometowns for less than 10 years, had worked in five cities or more, infrequently called family members, infrequently visited hometowns, migrated alone, reported poor Mandarin proficiency, had a low level of PBM, had engaged in five jobs or more and worked more than 8 h/day, compared with their corresponding counterparts.”

“Multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 2) revealed that young age, low monthly income, poor living condition, physical illness in the past 2 weeks, having worked in many cities, infrequently visiting hometown, poor Mandarin proficiency, a low level of PBM and working more than 8 h/day were independ- ently and positively associated with CMHPs. Taken together, these factors accounted for 27.6% of the vari- ance in the prevalence of CMHPs among these subjects.”

“The prevalence we found in migrant workers is similar to that reported among Latin American migrants of Australia (32.6%) (McDonald et al. 1996), among Romanian migrants of Spain (39.5%) (González-Castro & Ubillos, 2011) and among rural-to-urban migrants of Peru (38.0%) (Loret et al. 2012). The higher prevalence in migrant workers than Chinese general population and comparable prevalence between migrant workers and international migrants in this study support the increased risk of CMHPs in Chinese migrant workers.”

“In our migrant worker sample, as shown in Table 1, nearly two-thirds had an educational attainment of junior high school or below, about 50% were unmarried, over 70% had a monthly income of 599 USD or lower (lower than 50% of the average monthly income of urban residents), approximately 80% worked more than 8 h/day and nearly 40% migrated alone.”

“Perhaps there are particular pres- sures on young migrant workers arising from estab- lishing new careers and adapting to the new environment, often without support of parents and the extended family. There is evidence that a low socioeconomic status is associated with poor mental health (Muntaner et al. 2004; Lund et al. 2010); this is in accordance with our findings that migrant workers who had a low monthly income and poor living condi- tion had higher prevalence of CMHPs.”

“In the current study, infrequent visit of hometown was a risk factor for CMHPs. Because migrant workers are largely isolated from the mainstream of urban society (Zhong et al. 2015), family is the main available source of support for them when facing difficulties, though they work in remote cities.”

“Our study revealed that having worked in many cities was positively associated with CMHPs. As number of cities that migrant workers have worked in could be regarded as a measure of their mobility, this finding resembles the notion that high mobility is a risk factor for poor men- tal health of migrants (Ismayilova et al. 2014).”

“Similar to earlier findings in international migrants (Furnham & Li, 1993), migrant workers with difficul- ties in Mandarin were more likely to have CMHPs in this study. China has many dialects, migrant workers from various parts of China speak different dialects. Owing to their low level of education, migrant workers often have difficulties in speaking fluent Mandarin and have to face many barriers such as problems in commu- nication and making friends, which further increases the possibility of developing CMHPs.”

“Shenzhen is an extraordinary city, but until now, surprisingly little had been written about it.”

Gordon Mathews, Chinese University of Hong Kong

Eviction in Shenzhen (2018-present) is a long-term ethnographic series of experimental documentary films, which follow the planned demolition of my fathers ancestral village of Hubei in Shenzhen, China, as the government (Communist Party of China – CPC) initiates a major redevelopment plan to take its place. The proposed project includes an impressive 830m tall skyscraper, which will become the tallest building in the world, and will be accompanied with a modern shopping centre, restaurants, plus a small portion of Hubei Old Village preserved as a living museum and film location for hire. The films mark the eviction of the current tenants of the village who, as low-income workers, have to leave behind the cafes, food vendors, small businesses, residential homes and communities which they cultivated over a period of 10 – 20 years. Eviction in Shenzhen (2018-present) filmed over the course of this redevelopment period, will document these changes by recording the sociological make-up and ancient architecture of the village that is soon to disappear.

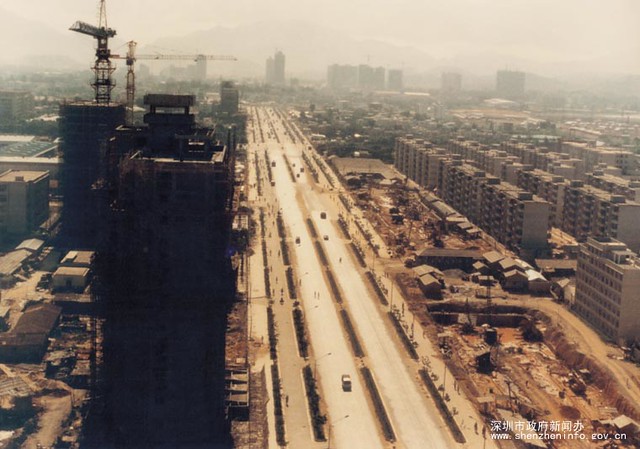

The new redevelopment will become one of China’s most prized architectural accomplishments, a visual spectacle, which pays homage to the economic miracle that is Shenzhen, as the city which led China to its new position as a global economical and technological power. If measured by economical and industrial standards, it is a city which is unarguably the most successful and most rapidly transformed in the world. Within four decades, the small peasant fishing village metamorphosed into a leading global manufacturer, producer and exporter of goods, providing electronics, toys, machinery, furniture and plastics to countries across the world. This transformation is a direct outcome of the economic reforms cultivated by former paramount leader, Deng Xiaoping. Deng knew that economic growth was intrinsically linked with global trade and cultivating relationships with foreign governments was essential to China’s growth, so in 1978, he sent a number of Chinese delegates around the world to learn how other countries were managing their own economic models. By 1979 they presented to the CPC the concept of the Special Economic Zone (SEZ); a free trade zone with loose regulations, special tax incentives and simple custom procedures with minimal intervention from central government. Based upon the Shannon Free Trade Zone in Ireland, the SEZ model rolled out to 4 strategically based cities in China. Shenzhen was its third, thus beginning the opening up of China to the rest of the world in 1986, as a global import/export trader.

At this point, Hong Kong’s manufacturing industries were already being challenged by skyrocketing land prices, a shortage of labour and the competition from nearby industrializing countries.

With the Open Policy of China, Hong Kong capitalists started to invest on the mainland. In the early 1980s, local industries began to move north in order to enjoy cheaper land and labour, and for language and cultural reasons, Hong Kong capitalists concentrated their operations in the Pearl River Delta, with Shenzhen and Dongguan being the favourite localities. Between 1979 and 2005, 64.7 % of Guangdong Province’s foreign investment came from Hong Kong. This led to the beginning of China opening up to the rest of the world in 1986, as a global import/export trader.

At this point, Hong Kong’s manufacturing industries were already being challenged by skyrocketing land prices, a shortage of labour and the competition from nearby industrializing countries.

With the Open Policy of China, Hong Kong capitalists started to invest on the mainland. In the early 1980s, local industries began to move north in order to enjoy cheaper land and labour, and for language and cultural reasons, Hong Kong capitalists concentrated their operations in the Pearl River Delta, with Shenzhen and Dongguan being the favourite localities. Between 1979 and 2005, 64.7 % of Guangdong Province’s foreign investment came from Hong Kong. This led to the beginning of China opening up to the rest of the world in 1986, as a global import/export trader.

With the SEZ model, the city could offer investors lower tax rates, global export/import routes through Shekou Port and Shenzhen Airport, as well as a mass, low-income workforce who were ready and eager for work. The increase of factories led to the creation of millions of jobs, thus attracting farmers and rural peasants from the nearby countryside to look for work within Shenzhen. These workers required urgent accommodation, so the CCP encouraged Shenzhen’s local peasants to transform their small properties into apartment blocks to house the increasing swathes of migrant workers.

My Aunt and Nan along with their neighbours, set upon this opportunity by collecting sand from the nearby mountains to make concrete, which they poured into hand-dug ditches to set foundations for 6-7 story flats (these flats were later coined as ‘wosholou’ or handshake buildings due to their close proximity to the adjacent apartments next door.) The flats elevated the fortunes of my family and their neighbours, transforming their lives from subsistence farmers into landlords with a steady and consistent income. The ancient Hubei Old Village became a bustling neighbourhood, hosting grocers, cafes, bakeries, merchants, food vendors, and providing residency for many thousands of rural migrants in the centre of the city.

As Shenzhen continued to expand, land became increasingly scarce and areas such as the urban villages gradually became valuable property for which the CPC wanted to reclaim. Considering the urban villages were seen as eyesores and festering slums, with their run-down mould-filled ancient walls and unsanitary and unclean streets, the sites fell out of favour with the central government’s future vision of China. Rather, they regarded the urban villages as an unappealing part of Chinese history for which they preferred to erase. In order to retrieve and repurpose the land, the CPC offered to buy back the leases from my family and their neighbours with an offer of compensation, to be awarded an apartment in the new development of their proposed project equivalent to the square meters of their old apartments and plots.

The closure of the once bustling Hubei Old village is particularly significant as it intersects upon a number of important sociological issues. For one, the urban village is considered to be one of the first settlements of Shenzhen as established 500 years ago by one of 3 Cheung brothers who are widely perceived to be the original founders of Shenzhen. This therefore marks the site as a place of ideological and historical value. Secondly, the forced evictions of the village residents and their lack of tenant rights show only one element to the human costs of this redevelopment project. By removing cheap accommodation, affordable services and amenities across the city, the service class are out-priced and given no option but to move elsewhere.

The minimisation of a low-income population coincides with the new AI reality of Shenzhen, as jobs originally facilitated by low-income workers are now in the process of being replaced by AI. Machines cook, serve food and make coffees to order, and factories, operate with machines which can work 24hrs without pay or fatigue, efficiently, replacing the teams of people who used to perform the same tasks before. Undeniably, the low-income population was vital to making Shenzhen the success story that it is today, evidently, the economical advancements of China would not have been possible without the many years of dedicated continuous physical labor from which its people performed. And whilst the media has rallied around the evictees to support their cause including state-backed newspaper Shenzhen Daily, the reports have not prevented the closure of these urban villages which are essential to housing these workers. Migrant workers such as those in Hubei Old Village, are evicted from their properties and as they close down their businesses and move out of their homes, a generation of migrants are cut off from the livelihoods and communities which some have spent decades to build. ‘Eviction in Shenzhen’, shot over the course of this period, records the sociological make-up of the village and ancient architecture of the site to document it before it rapidly disappears.