continuing to sketch > < continuing to sketch

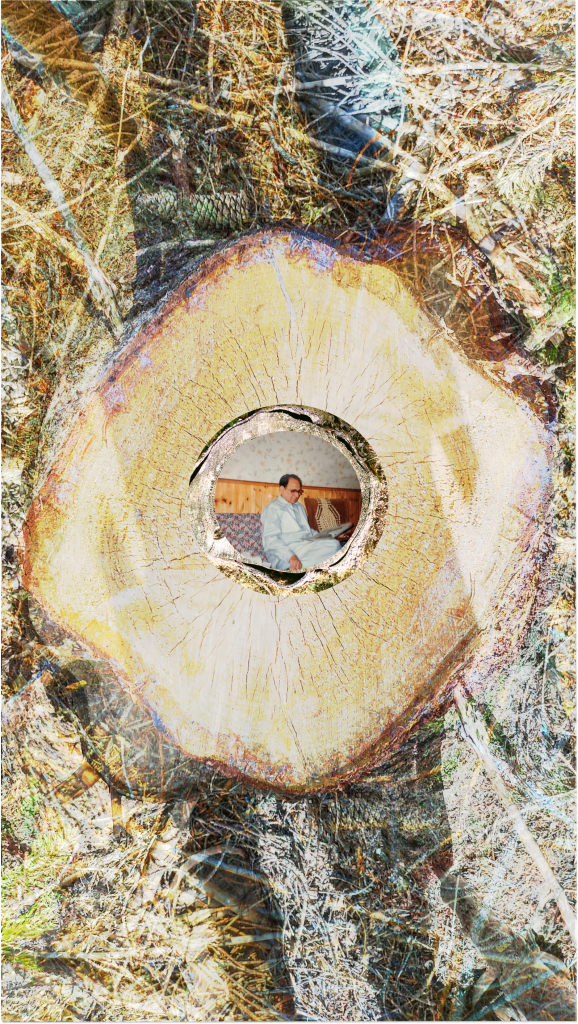

visible roots left in the ground > < follow up for the tree

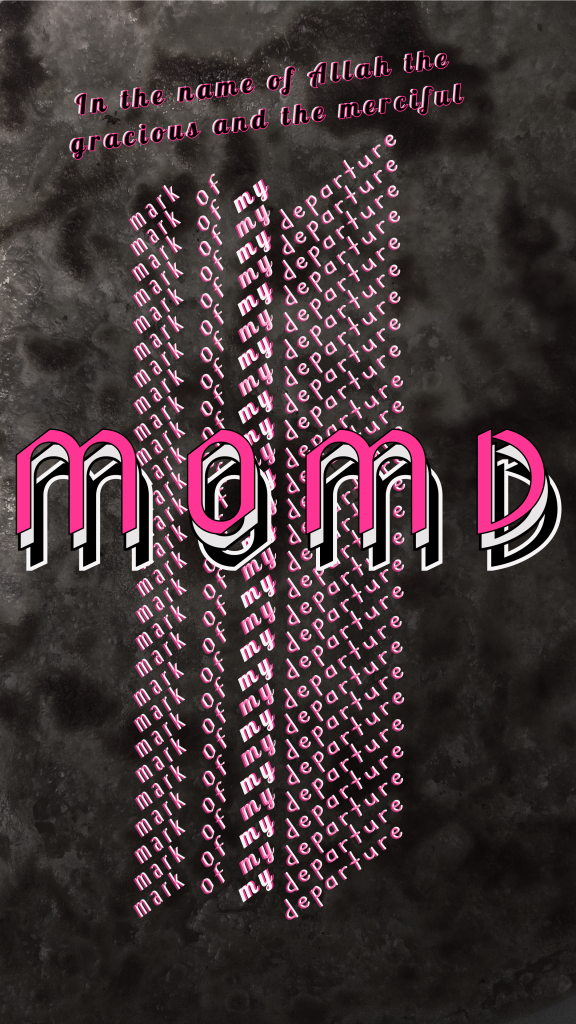

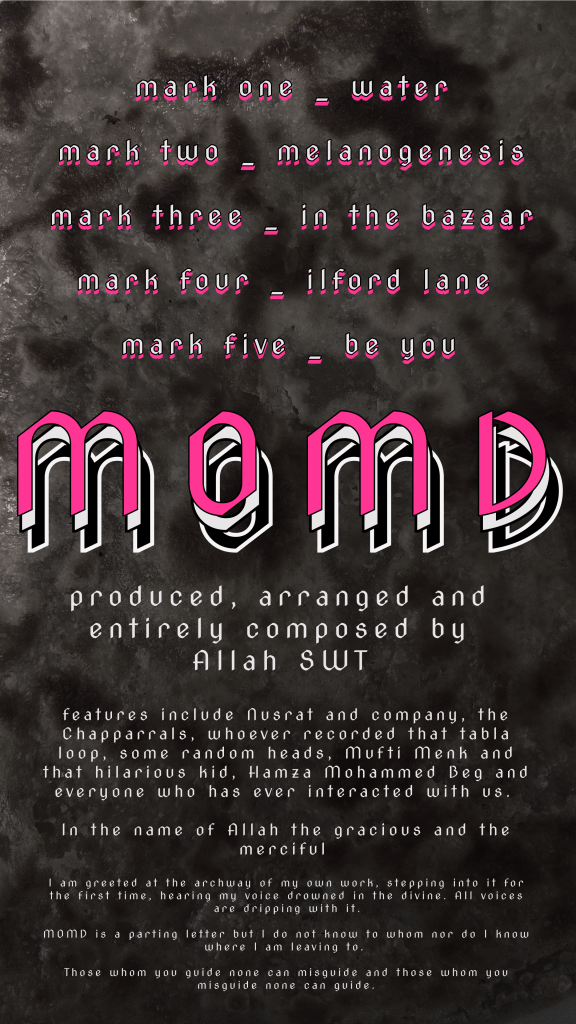

tabla tabla strings and vocals >

a call to recent studies >

video description: set to another Lollywood classic, this short clip splits the screen into two separate panels. Each one follows the camera movement from dead roots laid in the grass upward to a living tree and then up again to the blue sky – the movement is from grey decay to lush green and blue life. As the intro to the song finishes and the first vocal is about to drop in, the image pauses for a brief moment…two tabla-like images appear side to side. Both are rotating circles with an inner circle of a blackened wood texture, made to appear like the syahi, the central point of the tabla skin. Both rotating circles give the sense of vinyl records being played, with the outer ring on both circles featuring two distinct family images. One is of my two grandfathers sternly sizing each other up. The other is of my grandmother and her best friend sizing up the camera. As the song continues and fades out, the images are taken away by a burning line across the screen.