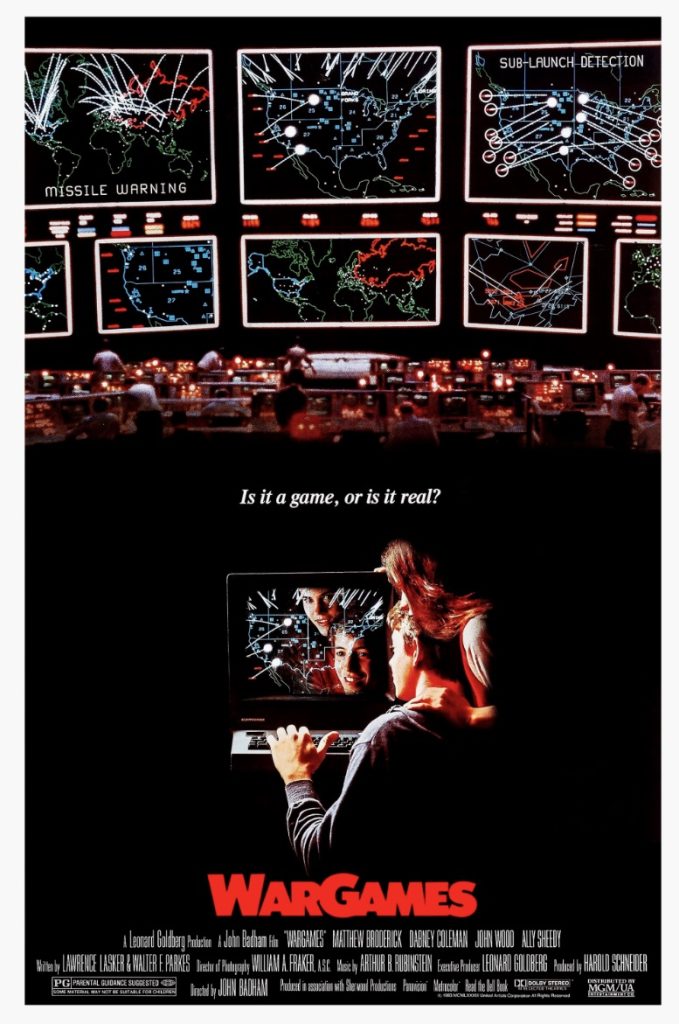

Made in the same year as the Serpukhov-15 incident, Wargames was a film that speculated on the beginnings of accidental war, automated weapons and hackable military facilities. The plot focuses on a high school teenager who discovers a backdoor into the computer that controls America’s nuclear weapons. Thinking it can’t possibly be a real military computer, the teenager at first thinks he’s playing a computer game, unable to comprehend the enormity of global violence now at his fingertips.

The computer itself was designed to replace human workers (those in power don’t want moral judgements and ethics to stand in the way) so it begins to play the ‘game’ back. And once it starts, it won’t stop.

The film’s tagline is ‘the only winning move is not to play’. Against the background of my research interests, it’s reminding me of something I read in Carissa Veliz’s book Privacy is Power: ‘the internet does not allow you to remain silent’ (p230). It is incredibly difficult to opt out of systems of surveillance and networks that amass data for ‘algorithms of oppression’, to borrow a phrase from Safiya Umoja Noble.

The technologies of such systems of control rely on our inputs, which is why the issue of choice is so pertinent.

In the film, choice was looked at through the lens of computer automated weaponry.

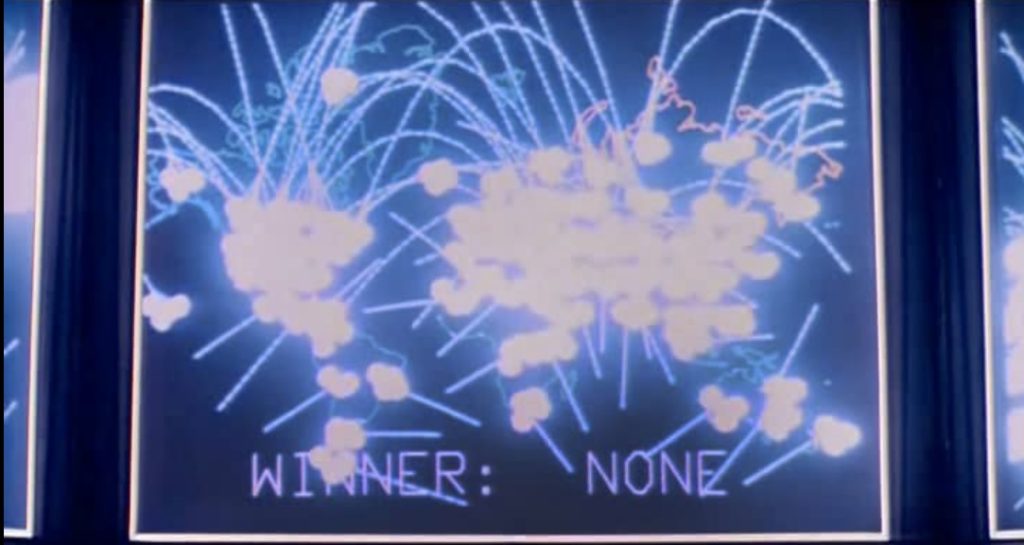

Finally, in Wargames, to stop the computer and to avert catastrophic destruction, they have to convince it that continuation is futile. The competitive cycle of input and response must stop. There are no winners in nuclear war.

I’m wondering what I can take away from this in relation to my research. Maybe it’s that there are no winners when huge amounts of the population are criminalised, subjected to limited opportunities, and marginalised and discriminated against by opaque computerised processes.