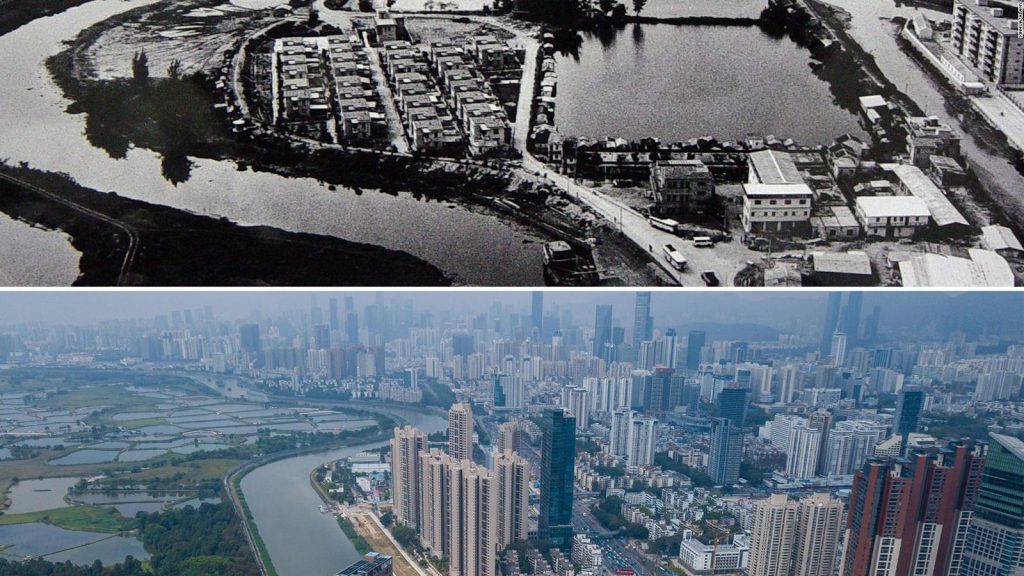

This new redevelopment in Hubei Old Village, will become one of China’s most prized architectural accomplishments, a visual spectacle, which pays homage to the economic miracle that is Shenzhen, as the city which led China to its new position as a global economical and technological power. If measured by economical and industrial standards, it is a city which is unarguably the most successful and most rapidly transformed in the world. Within four decades, the small peasant fishing village metamorphosed into a leading global manufacturer, producer and exporter of goods, providing electronics, toys, machinery, furniture and plastics to countries across the world.

This transformation is a direct outcome of the economic reforms cultivated by former paramount leader, Deng Xiaoping. Deng knew that economic growth was intrinsically linked with global trade and cultivating relationships with foreign governments was essential to China’s growth, so in 1978, he sent a number of Chinese delegates around the world to learn how other countries were managing their own economic models. By 1979 they presented to the CPC the concept of the Special Economic Zone (SEZ); a free trade zone with loose regulations, special tax incentives and simple custom procedures with minimal intervention from central government. Based upon the Shannon Free Trade Zone in Ireland, the SEZ model rolled out to 4 strategically based cities in China, and Shenzhen was its third, thus beginning the opening up of China to the rest of the world in 1986, as a global import/export trader.

Hong Kong at the time, which was close to the border of Shenzhen, was already beginning to shut down its manufacturing sector, leaving Shenzhen, readily available to take on the work. With the SEZ model, the city could offer investors lower tax rates, global export/import routes through Shekou Port and Shenzhen Airport, as well as a mass, low-income workforce who were ready and eager for work. The increase of factories led to the creation of millions of jobs, thus attracting farmers and rural peasants from the nearby countryside to look for work within Shenzhen. These workers required urgent accommodation, so the CPC encouraged Shenzhen’s local peasants to transform their small properties into apartment blocks to house the increasing swathes of migrant workers. The CPC incentivised the peasants by giving them back the leases to their land, and promised them that the profits that they’d make would be theirs to keep. My Aunt and Nan along with their neighbours, set upon this opportunity by collecting sand from the nearby mountains to make concrete, which they poured into hand-dug ditches to set foundations for 6-7 story flats (these flats were later coined as wosholou or handshake buildings due to their close proximity to the adjacent flats next door.) The flats elevated the fortunes of my family and their neighbours, transforming their lives from subsistence farmers into landlords with a steady and consistent income. The ancient Hubei Old Village became a bustling neighbourhood, hosting grocers, cafes, bakeries, merchants, food vendors, and providing residency for many thousands of rural migrants in the centre of the city.

As Shenzhen expanded, land became increasingly scarce and areas such as the urban villages gradually became valuable property for which the CPC wanted to reclaim. Considering the urban villages were seen as eyesores and festering slums, with their run-down mould-filled ancient walls and unsanitary and unclean streets, the sites fell out of favour with the central government’s future vision of China. Rather, they regarded the urban villages as an unappealing part of Chinese history for which they preferred to erase. In order to retrieve and repurpose the land, the CPC offered to buy back the leases from my family and their neighbours with an offer of compensation, to be awarded an apartment in the new development of their proposed project equivalent to the square meters of their old apartments and plots.