Jamie Wyld (Vital Capacities’ director): Really great to have you as part of the Vital Capacities residency programme! Can you say a little about yourself and your work, perhaps in relation to what you’re thinking about doing during the residency?

Damien Robinson: Hi Jamie! Thank you for asking me to take part!

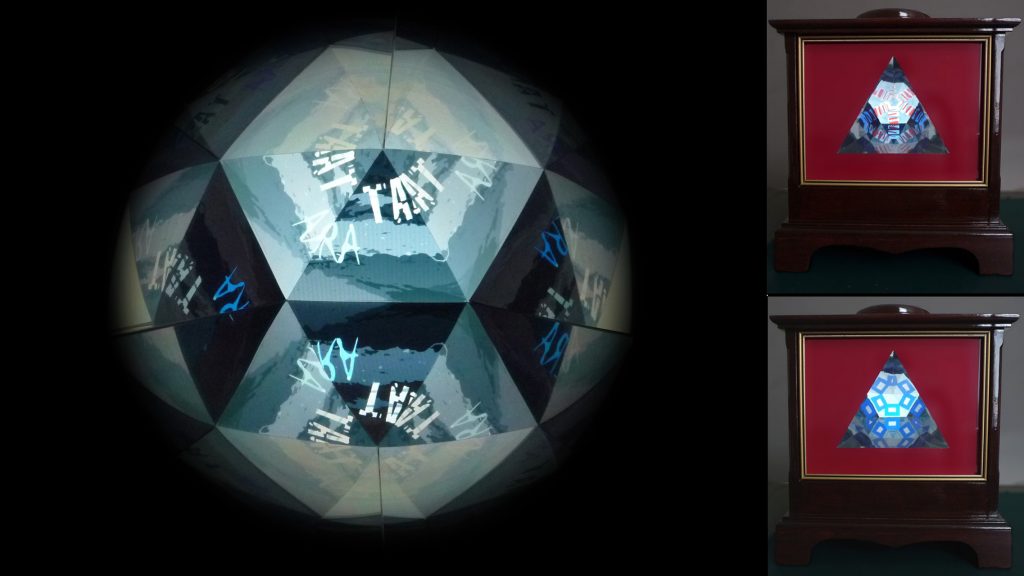

I’m Damien, I’m a visual artist working with mixes of digital and non-digital approaches. My practice was originally print-based and I used to make three-dimensional work; over time I began incorporating digital processes, particularly around using discarded technologies and open-source software. I was lucky enough to get the chance to work with Mediashed, which was really forward thinking in terms of artist collaboration and teaching us about free media concepts. As a deaf artist I’d had little access to formal learning; even during my degree I wasn’t allowed to learn about or use huge amounts of equipment because I apparently constituted a health and safety risk, so I went about a lot of things the “wrong way”. The Mediashed experience involved thinking differently about hardware and software, so I began enjoying mis-using processes and technologies, something I still do now.

Recently I’ve been working as part of “The Agency of Visible Womxn” (AoVW), an Intersectional Artist Network, resulting in collaborative and solo works using a mix of digital, print and discarded tech. So during the residency, I’ll be picking out elements of that real/virtual intersect, informed by so many things I’ve learned from and with Agency artists.

JW: One of the aims of Vital Capacities is to create an accessible site (so more people can use it) – how do you think this will be an opportunity to develop your way of working?

DR: As an artist with a sensory impairment (deaf), I’m aware that while I work visually, that can create obstacles for people with other impairments, particularly visual impairments. Having to work in a more isolated way this year has increased the challenges of making accessible work as an individual artist. But I think there are potential creative outcomes from working within the residency structure that can support me in looking at access. So If I’m thinking about – say a sound effect has been transcribed into text, and I then create a (visual) caption with the text, then having that caption audio-described might give another creative layer to the process. And I’m sure I’ll learn a lot more about other access issues that I can take forward in my practice.

JW: What would you like to achieve through the residency? Is there a particular project you’ll be focusing on?

DR: The residency is going to give me an opportunity to focus back on my individual practice for a while. Like many artists, much of my income was secured through offshoots of my practice rather than physically selling work. In my case, that’s been through education work and community projects – so obviously I had a domino runs of cancellations from March onwards. I’ve been lucky to find some alternative work, and to already have been working with AoVW and TOW, but my practice took the impact of having to change direction.

However, it has meant that some ideas I had years back have started to resurface, particularly thinking around text and distortion of the written and spoken word. In relation to computer-based typesetting and AI transcription, some of the issues around text accuracy have deep (and distorted) connections to accessibility and gender issues. I have a form of RSI and was originally advised to use voice recognition software – not easy for a deaf person and I never got any benefit from it, despite expending a lot of time and money.

A discussion last year with another Agency artist (who has dyslexia) around the book “Invisible Women” gave us both a lightbulb moment that speech-to-text software is built around male voice algorithms, which meant it was flawed for us from the start. It was never going to work the way we were told it would. And although I work with BSL interpreters for online meetings, I use Otter transcription as I can’t take notes, and – well, there are issues, particularly when women speak.

I’ve also found myself looking again at sound transcription, and the differences between HAC captioning and AI transcription. I’ve been pondering the subtitling of ambient sound and sound effects rather than words; the BBC have editorial guidelines on subtitling and when it is permissible to subtitle a sound phonetically rather than in words; “lions roar” versus “Rrrarrgghhh!”. And I’m hoping to bring some of this back to the connections I have with TOW and use the digital/printmaking intersect that’s achievable with risograph. So, lots of ideas – we’ll see where they go.

Notes:

Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men – Caroline Criado Perez

(www.carolinecriadoperez.com/books)

HAC – Human Aid to Communication

JW: How do you see the next few weeks unfolding? Where would you like it to take you?

DR: It’s such a great opportunity to start unpacking some ideas and really begin working with them, rather than putting them at the bottom of a very long list of things to do. It may be that I’ll come up with something completed, or that this will only be the start of something that needs a longer-term period to develop. But again like many artists, a lot of the exploratory and developmental side of my practice doesn’t get seen, and I think showing process as well as “product” is important in showing the submerged elements of digital practice.

To find out more about Damien’s work, visit her studio space.