Introduction

“Shenzhen is an extraordinary city, but until now, surprisingly little had been written about it.”

Gordon Mathews, Chinese University of Hong Kong

Eviction in Shenzhen (2018-present) is a long-term ethnographic series of experimental documentary films, which follow the planned demolition of my fathers ancestral village of Hubei in Shenzhen, China, as the government (Communist Party of China – CPC) initiates a major redevelopment plan to take its place. The proposed project includes an impressive 830m tall skyscraper, which will become the tallest building in the world, and will be accompanied with a modern shopping centre, restaurants, plus a small portion of Hubei Old Village preserved as a living museum and film location for hire. The films mark the eviction of the current tenants of the village who, as low-income workers, have to leave behind the cafes, food vendors, small businesses, residential homes and communities which they cultivated over a period of 10 – 20 years. Eviction in Shenzhen (2018-present) filmed over the course of this redevelopment period, will document these changes by recording the sociological make-up and ancient architecture of the village that is soon to disappear.

Historical Context

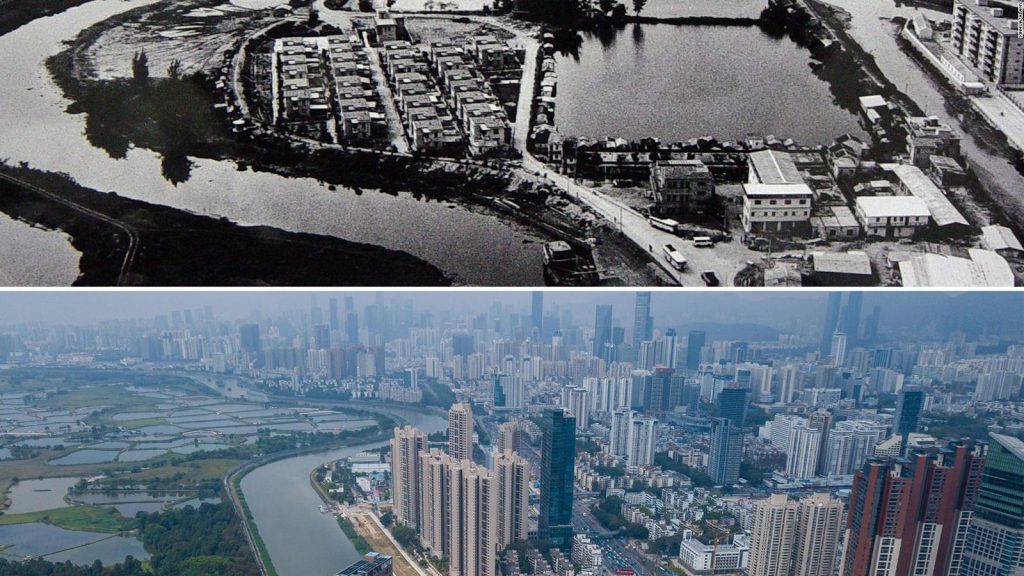

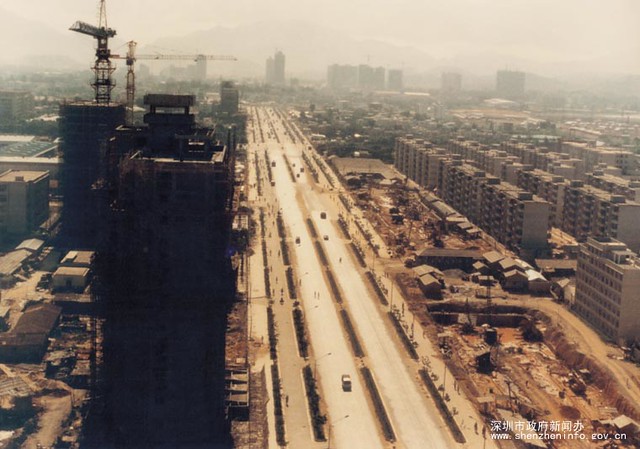

The new redevelopment will become one of China’s most prized architectural accomplishments, a visual spectacle, which pays homage to the economic miracle that is Shenzhen, as the city which led China to its new position as a global economical and technological power. If measured by economical and industrial standards, it is a city which is unarguably the most successful and most rapidly transformed in the world. Within four decades, the small peasant fishing village metamorphosed into a leading global manufacturer, producer and exporter of goods, providing electronics, toys, machinery, furniture and plastics to countries across the world. This transformation is a direct outcome of the economic reforms cultivated by former paramount leader, Deng Xiaoping. Deng knew that economic growth was intrinsically linked with global trade and cultivating relationships with foreign governments was essential to China’s growth, so in 1978, he sent a number of Chinese delegates around the world to learn how other countries were managing their own economic models. By 1979 they presented to the CPC the concept of the Special Economic Zone (SEZ); a free trade zone with loose regulations, special tax incentives and simple custom procedures with minimal intervention from central government. Based upon the Shannon Free Trade Zone in Ireland, the SEZ model rolled out to 4 strategically based cities in China. Shenzhen was its third, thus beginning the opening up of China to the rest of the world in 1986, as a global import/export trader.

At this point, Hong Kong’s manufacturing industries were already being challenged by skyrocketing land prices, a shortage of labour and the competition from nearby industrializing countries.

With the Open Policy of China, Hong Kong capitalists started to invest on the mainland. In the early 1980s, local industries began to move north in order to enjoy cheaper land and labour, and for language and cultural reasons, Hong Kong capitalists concentrated their operations in the Pearl River Delta, with Shenzhen and Dongguan being the favourite localities. Between 1979 and 2005, 64.7 % of Guangdong Province’s foreign investment came from Hong Kong. This led to the beginning of China opening up to the rest of the world in 1986, as a global import/export trader.

At this point, Hong Kong’s manufacturing industries were already being challenged by skyrocketing land prices, a shortage of labour and the competition from nearby industrializing countries.

With the Open Policy of China, Hong Kong capitalists started to invest on the mainland. In the early 1980s, local industries began to move north in order to enjoy cheaper land and labour, and for language and cultural reasons, Hong Kong capitalists concentrated their operations in the Pearl River Delta, with Shenzhen and Dongguan being the favourite localities. Between 1979 and 2005, 64.7 % of Guangdong Province’s foreign investment came from Hong Kong. This led to the beginning of China opening up to the rest of the world in 1986, as a global import/export trader.

With the SEZ model, the city could offer investors lower tax rates, global export/import routes through Shekou Port and Shenzhen Airport, as well as a mass, low-income workforce who were ready and eager for work. The increase of factories led to the creation of millions of jobs, thus attracting farmers and rural peasants from the nearby countryside to look for work within Shenzhen. These workers required urgent accommodation, so the CCP encouraged Shenzhen’s local peasants to transform their small properties into apartment blocks to house the increasing swathes of migrant workers.

My Aunt and Nan along with their neighbours, set upon this opportunity by collecting sand from the nearby mountains to make concrete, which they poured into hand-dug ditches to set foundations for 6-7 story flats (these flats were later coined as ‘wosholou’ or handshake buildings due to their close proximity to the adjacent apartments next door.) The flats elevated the fortunes of my family and their neighbours, transforming their lives from subsistence farmers into landlords with a steady and consistent income. The ancient Hubei Old Village became a bustling neighbourhood, hosting grocers, cafes, bakeries, merchants, food vendors, and providing residency for many thousands of rural migrants in the centre of the city.

As Shenzhen continued to expand, land became increasingly scarce and areas such as the urban villages gradually became valuable property for which the CPC wanted to reclaim. Considering the urban villages were seen as eyesores and festering slums, with their run-down mould-filled ancient walls and unsanitary and unclean streets, the sites fell out of favour with the central government’s future vision of China. Rather, they regarded the urban villages as an unappealing part of Chinese history for which they preferred to erase. In order to retrieve and repurpose the land, the CPC offered to buy back the leases from my family and their neighbours with an offer of compensation, to be awarded an apartment in the new development of their proposed project equivalent to the square meters of their old apartments and plots.

Contemporary Context

The closure of the once bustling Hubei Old village is particularly significant as it intersects upon a number of important sociological issues. For one, the urban village is considered to be one of the first settlements of Shenzhen as established 500 years ago by one of 3 Cheung brothers who are widely perceived to be the original founders of Shenzhen. This therefore marks the site as a place of ideological and historical value. Secondly, the forced evictions of the village residents and their lack of tenant rights show only one element to the human costs of this redevelopment project. By removing cheap accommodation, affordable services and amenities across the city, the service class are out-priced and given no option but to move elsewhere.

The minimisation of a low-income population coincides with the new AI reality of Shenzhen, as jobs originally facilitated by low-income workers are now in the process of being replaced by AI. Machines cook, serve food and make coffees to order, and factories, operate with machines which can work 24hrs without pay or fatigue, efficiently, replacing the teams of people who used to perform the same tasks before. Undeniably, the low-income population was vital to making Shenzhen the success story that it is today, evidently, the economical advancements of China would not have been possible without the many years of dedicated continuous physical labor from which its people performed. And whilst the media has rallied around the evictees to support their cause including state-backed newspaper Shenzhen Daily, the reports have not prevented the closure of these urban villages which are essential to housing these workers. Migrant workers such as those in Hubei Old Village, are evicted from their properties and as they close down their businesses and move out of their homes, a generation of migrants are cut off from the livelihoods and communities which some have spent decades to build. ‘Eviction in Shenzhen’, shot over the course of this period, records the sociological make-up of the village and ancient architecture of the site to document it before it rapidly disappears.